Bar a few drug dealers' corpses, Rodrigo Roa Duterte's Philippines is off to a good start

Millions of Filipinos trust their new leader, despite his hard-line position on the drugs trade

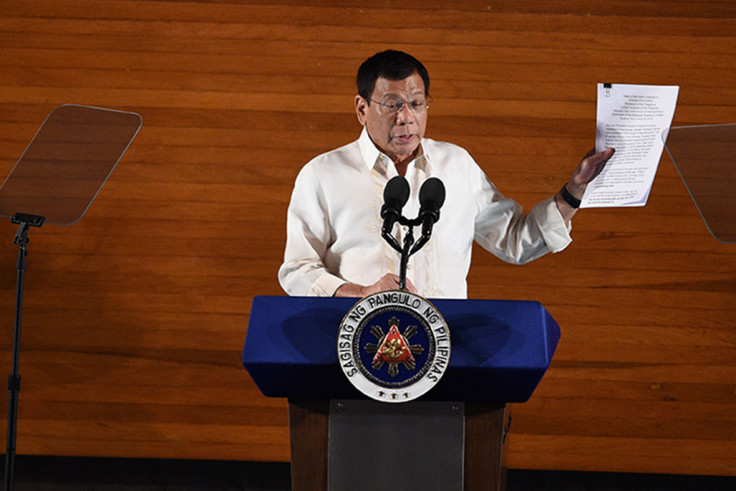

Despite gaffes that came off as insensitive to media killings, statements that seem to give license to commit human rights violations, and extremely high expectations as the 16th president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Roa Duterte seems to be off to a promising start to his six-year term.

On Monday (25 July) he delivered his first State of the Nation Address before a bicameral Congress and millions of Filipinos the through media – some 91% of whom told a recent national survey that they trusted him as president. That trust rating, reported by Pulse Asia last week, was higher than the 85% that Benigno "Noynoy" Aquino III received when he started his presidential term in 2010, despite the fact that he was elected by a higher percentage of voters than Duterte.

Besides high trust ratings, Duterte also has a rapidly growing economy to bolster his capability to govern. A major economic driving force is the remittances from overseas workers, amounting to $26.93bn in 2015, according to the Philippine central bank. Also, the Philippines has a robust business process outsourcing (BPO) sector that also contributes substantially to the economy, forecasted by one company to hit $25bn this year and is expected to eventually surpass the annual remittances.

There is also optimism brought about by the economic integration of Asean, a bloc of 10 countries that includes the Philippines. Asean, or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is a $2.6trn market with about 622 million people. If taken together, Asean's economy would be the seventh largest in the world as of 2014. So, not only does the Philippine economy on its own hold much promise, it also poised to benefit from the expected growth in the region.

The state of the Philippine economy, however, represents the only a facet of the overall outlook. Duterte was elected largely over concerns – and frustrations regarding over the government's inability to deal with the drug problem in the country. Recent reports estimated that 92% of villages or wards in the country have been infiltrated by the illegal drug trade. A village or "barangay" is the basic political unit in the Philippines.

Duterte's popularity as a presidential candidate may be attributed to his image of being tough on criminals when he was mayor of Davao, a major city in the southern island of Mindanao. But his critics have cited this tough talk, particularly his threats to kill criminals and boasts of having eliminated such people before in Davao, as worrisome.

So far, though, the threatening messages have compelled thousands of drug users and pushers to surrender to law enforcement officials, perhaps out of fear that Duterte would make good on his promise. Already, scores have died in killings since Duterte won the elections.

But critics note that no major drug crime personality has been targeted so far, although five active and recently retired police generals are being investigated after they were named by the president as alleged protectors of drug lords operating in the country. It is widely suspected here that the drug trade is controlled by crime syndicates based in China, but that country poses yet another problem for Duterte.

Foreign and domestic fronts

China's shadow looms large over the Philippines, with whom it is arguing over sovereignty in parts of the West Philippines Sea, the local name for the South China Sea. The Philippines recently "won" its case before an international tribunal, but even before the decision was announced, China declared that it would not acknowledge any ruling.

During the campaign, Duterte said in a televised debate that he would ride a jet ski to the disputed territories and plant the Philippine flag there in a symbolic gesture to assert sovereignty. But his moves since his election have been more rational, if not statesman-like. He has met at least twice with the Chinese ambassador in Manilla, and has even expressed willingness to open bilateral talks with Beijing, something that his predecessor refused to do. But the talks have hit a snag with Beijing's insistence that the Philippines set aside the arbitration ruling.

The Philippines is hoping to rally international support against what it calls "bullying" by China. But from Beijing's perspective, the Philippines is the aggressor, particularly with its calls for the United States to defend the country against the Chinese. Meanwhile, the US has been increasing its military presence in the Philippines as part of its pivot to Asia and its foreign policy aim to ensure freedom of navigation.

Increased American presence in the Philippines has not been welcomed by all, though. The local communists, along with its armed wing the New People's Army, have expressed misgivings about the growing American military presence here. The communists have waged a three-decade long rebellion against the government, but the prospects of peace have been rekindled by Duterte's election. He was the former student and friend of Joma Sison, the exiled leader and founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines.

Sison has openly praised Duterte, and he has dispatched his secretary in charge of the peace process to meet with communist leaders and possibly revive the peace talks that stalled during the last administration.

The Duterte government is also trying to work out a peace agreement with Muslim secessionists. Tensions ran high after the Aquino administration failed to push a bill that was the product of talks between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). Some lawmakers and other critics argue it had provisions that violated the Philippine constitution, and that the consultation process had bypassed or ignored key stakeholders, including the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), which had signed a peace treaty with the government in the 1990s. The MILF had sprang from the MNLF, and as the former was talking with the Aquino government, other rebels have formed their own breakaway faction.

Duterte has been advocating a change to a federal form of government, which he argued would address the concerns of Filipino Muslims who feel that their needs and concerns have been ignored by "imperial Manila." But the change would require overhauling the 1986 Constitution, the present law of the land. While it is not yet clear how that change would be realised, Duterte and other top leaders have expressed a preference for convening a constitutional convention, which would be tasked to draft a new constitution and create a federal structure that would be voted on by Filipinos in a plebiscite.

Change has begun

The process of changing the constitution is long and difficult. Previous presidents have tried and failed. Meanwhile, the Duterte government faces other major issues.

One such issue is the traffic congestion, which the government estimated costs the economy Php3bn ($64bn) a day, around 0.8% of the gross domestic product. A study funded by JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) reported that the economic cost of traffic congestion could reach Php6 billion a day by 2030. To its credit, the Duterte government included robust infrastructure development among its top 10 priorities.

Not only will increased public spending hasten economic growth, it will also address a key failing of the previous government to create jobs. The government's unemployment rate is about 7%, but a recent survey by Social Weather Stations (SWS) claims that adult joblessness is actually 23.9%, based on its respondents. That figure represents some 11 million of the population, if accurate.

Despite the rapid growth rate of the Philippine economy mentioned earlier, income equality remains a challenge for the government's economic managers and other policymakers here. "Inclusive growth" was a battle cry of the previous government, but its critics have argued that it was an unfulfilled promise.

Duterte's government also offered promises, and they have been well received so far. But Filipinos, especially the poor, have been disappointed many times before. Still, people here believe that Duterte deserves a fair chance. Many personalities in media and in other sectors have offered to observe a "honeymoon period," where they would tone down their criticisms of the new President during his early days in office.

And so with the verdict on Duterte still forthcoming, it may be safe to say for now that for the most part, Filipinos are cautiously optimistic.

Dante Ang is executive editor, president and chief executive officer of The Manila Times, the oldest newspaper in the Philippines.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.