Bat-human disease risk is mapped across the globe, showing Ebola could appear in more places

The most at-risk areas of the world for bat-human virus transmissions have been mapped, showing West Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia as the hotspots. The research builds upon the devastating Ebola virus crisis, which has killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa.

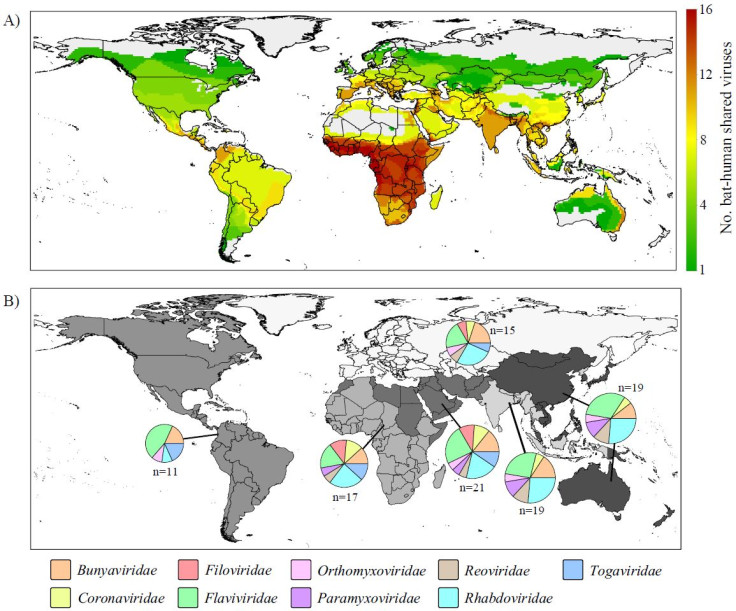

Researchers wanted to find the risk of similar events occurring across the globe. They found that West Africa is not the only part of the world which is at risk from bat viruses spilling over to humans. The mapped information shows that Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and South America are also at risk.

"We've identified the factors contributing to the transmission of zoonotic diseases, allowing us to create risk maps for each," said Kate Jones, lead researcher in the study. "For example, mapping for potential human-bat contact, we found Sub-Saharan Africa to be a hotspot. Whereas for diversity of bat viruses, we found South America was at most risk. By combining the separate maps, we've created the first global picture of the overall risks of bat viruses infecting humans in different regions."

Diseases that are transmitted to humans from animals are known as 'zoonotic', and they represent 60-75% of all human emerging infectious diseases. Bats are considered a major source of zoonotic diseases – even more per species than rodents – and are believed to be responsible for Ebola, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and rabies.

Two maps were created to assess the risk of bat-human virus transferral, published in American Naturalist. The researchers, from University College London, showed that the number of known viruses that have become zoonotic in different areas of the world, as well as the genetic diversity of these viruses.

The scientists analysed bat data spanning 113 years – 1900 to 2013. They modelled information for number of zoonotic bat viruses and the number of bat species from nearly 500 different sets of data.

Once they combined the model with human population data, the map patterns became clear.

"We are seeing risk hotspots for emerging diseases where there are large and increasing populations of both humans and their livestock," said researcher Liam Brierley.

"As a result, settlements and industries are expanding into wild areas such as forests and this is increasing contact between people and bats. People in these areas may also hunt bats for bushmeat, unaware of the risks of transmissible diseases which can occur through touching body fluids and raw meat of bats."

Brierley added: "There's still some way to go in monitoring virus diversity in wild animals and specific information on infections that would allow us to create higher-resolution maps. With advances in technology, we anticipate the way we collect and share data to improve, potentially stopping future pandemics."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.