Biologists slow ageing process, extending lifespan of fruit flies

Researchers hope the technique could one day benefit humans.

Biologists from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have developed a method to slow the ageing process in fruit flies, extending their lifespan. The technique – which behaves as a kind of cellular time machine, acting on a key component of ageing – significantly improved the health of the animals.

The team hopes the development could lead to treatments that delay the onset of a host of age-related ailments such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, cancer, strokes and cardiovascular disease.

Fruit flies are often used for studies on ageing because their short two-month lifespan allows scientists to trace the effects of specific treatment in a manageable time period, while many of the features of ageing at a cellular level are similar to those of humans. Furthermore, researchers have identified all of the fruit fly's genes and have the ability to switch individual ones on and off for a desired effect.

In developing the technique, the researchers focused on mitochondria – the tiny powerhouses inside cells that fuel their growth and determine when they live and die. As people age, their mitochondria often become damaged, accumulating in the brain, muscles and other organs.

This poses a problem because the damaged mitochondria can become toxic, damaging the cells where any build-up occurs. This process is a contributing factor to many age-related diseases.

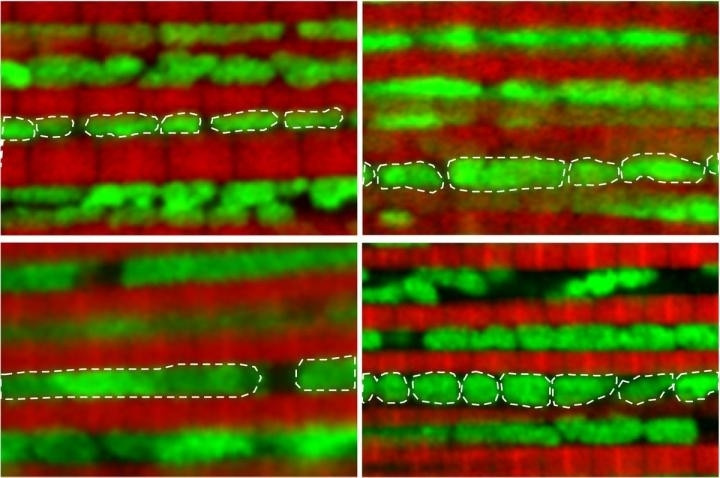

The new study, published in the journal Nature Communications, found that as fruit flies reach middle-age – a month into their lives – their mitochondria start to change from their original small, round shape, becoming larger.

"We think the fact that the mitochondria become larger and elongated impairs the cell's ability to clear the damaged mitochondria," said David Walker, a UCLA professor and senior author of the study. "And our research suggests dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate with age, rather than being discarded."

The UCLA researchers treated the flies by removing the damaged mitochondria, breaking them up into smaller pieces. They found that this caused the flies to become more energetic and also enabled them to live longer than usual – females lived 20% longer, while males lived 12% longer.

The study highlights the significance of a type of protein called Drp1 in the ageing process. In flies and mice, levels of Drp1 decline with age. To help break apart and remove the flies' damaged mitochondria, the scientists increased their levels of Drp1 for one week when they were one month old.

In addition to this, Anil Rana, another author of the study, demonstrated an additional important factor – that a gene called Atg1 helps turn back the clock on cellular ageing. He did this by essentially 'turning off' the gene hindering the flies' ability to remove the damaged mitochondria.

This proved to the team that the Atg1 gene was essential for the anti-ageing technique to work. The Drp1 protein breaks up the damaged mitochondria while the Atg1 gene is required to get rid of them.

"It's like we took middle-aged muscle tissue and rejuvenated it to youthful muscle," said Walker. "We actually delayed age-related health decline. And seven days of intervention was sufficient to prolong their lives and enhance their health."

Walker hopes that the anti-ageing technique his team have developed could one day enable humans to slow the process, extending people's lives and delaying the onset of age-related diseases.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.