Brazil dam disaster: Toxic red mud threatens endangered wildlife in Rio Doce basin

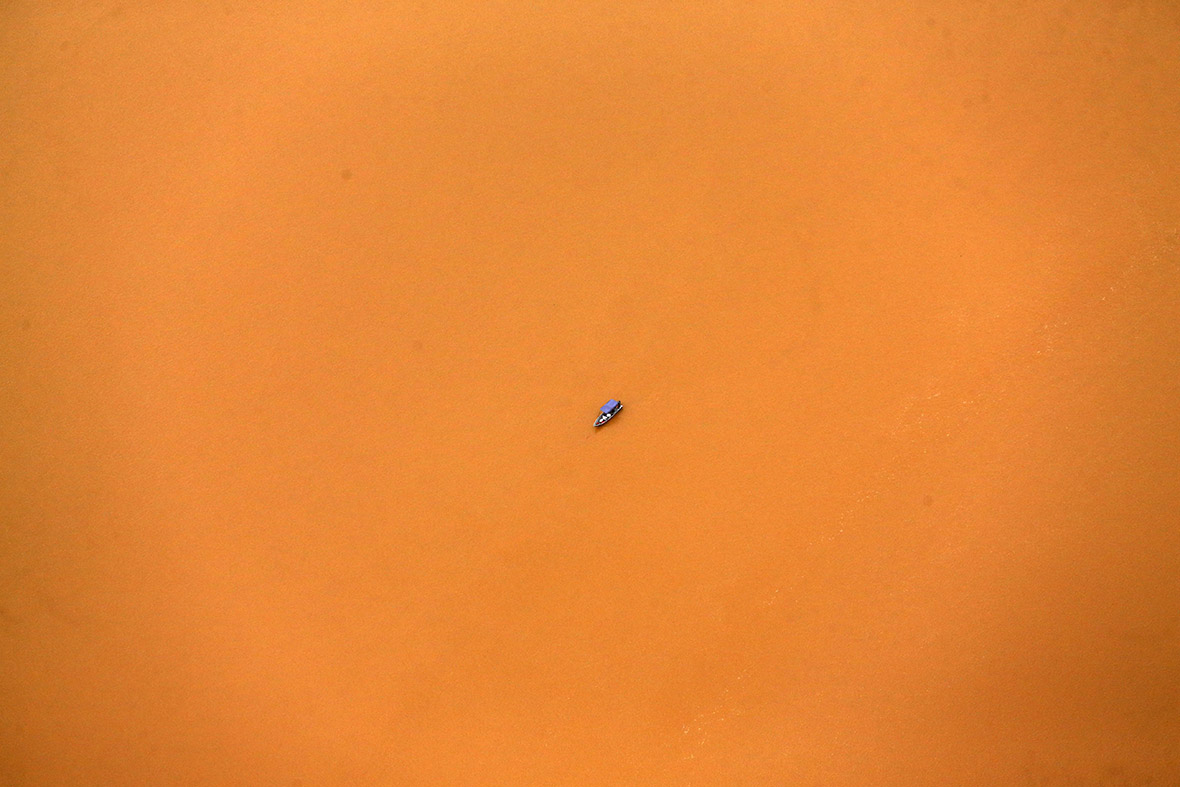

Toxic mud from a collapsed iron mine dam in Brazil has travelled more than 500km along the Rio Doce to reach the Atlantic Ocean. A plume of red mud can be seen spreading out along the coast of the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo, threatening the region's already endangered wildlife.

The collapse of the dam caused Brazil's worst ever environmental disaster. Sixty million cubic metres of iron ore waste – enough to fill 25,000 Olympic-size swimming pools – engulfed villages and contaminated rivers in south-east Brazil on 5 November.

Eleven people were killed and 12 people remain missing, presumed buried in the mud.

The Minas Gerais Institute of Water Management said it has detected toxic substances such as mercury, arsenic, chromium and manganese at levels exceeding human consumption limits in the contaminated mud. Biologists say it could take 30 years to clean up the Rio Doce basin.

Samarco, the mine operator, has contracted local fishermen to bury dead fish that wash up on beaches near the mouth of the river. Fishermen in the Linhares region of Espirito Santo are being paid to collect from the sand the fish they once caught in the sea. The fishermen have been offered 100 Brazilian reais (£17.73 or $27) per day, with others hiring out their boats to the mining company for an extra fee.

Andres Ruchi, director of the Marine Biology school in Santa Cruz, said the mud could be a disaster for the many species of marine life that feed and breed near the river mouth, including fish, leatherback and loggerhead turtles, whales and dolphins. Scientists say the sediment could reduce oxygen and alter pH levels in the water, causing great harm to aquatic life.

The tide of toxic red mud threatens the Comboios nature reserve, one of the only regular nesting sites for the endangered leatherback turtle. Conservationists are also closely watching loggerhead sea turtles as they lay their eggs on beaches near the mouth of the river.

The Brazilian Environment Institute (Ibama) and the Chico Mendes Conservation and Biodiversity Institute (ICMBio) have begun removing young turtles from the area, in an effort to protect the most endangered species and the biodiversity of the region.

The iron ore mine is owned by Samarco, a joint venture between the mining giants Vale of Brazil and BHP Billiton of Australia.

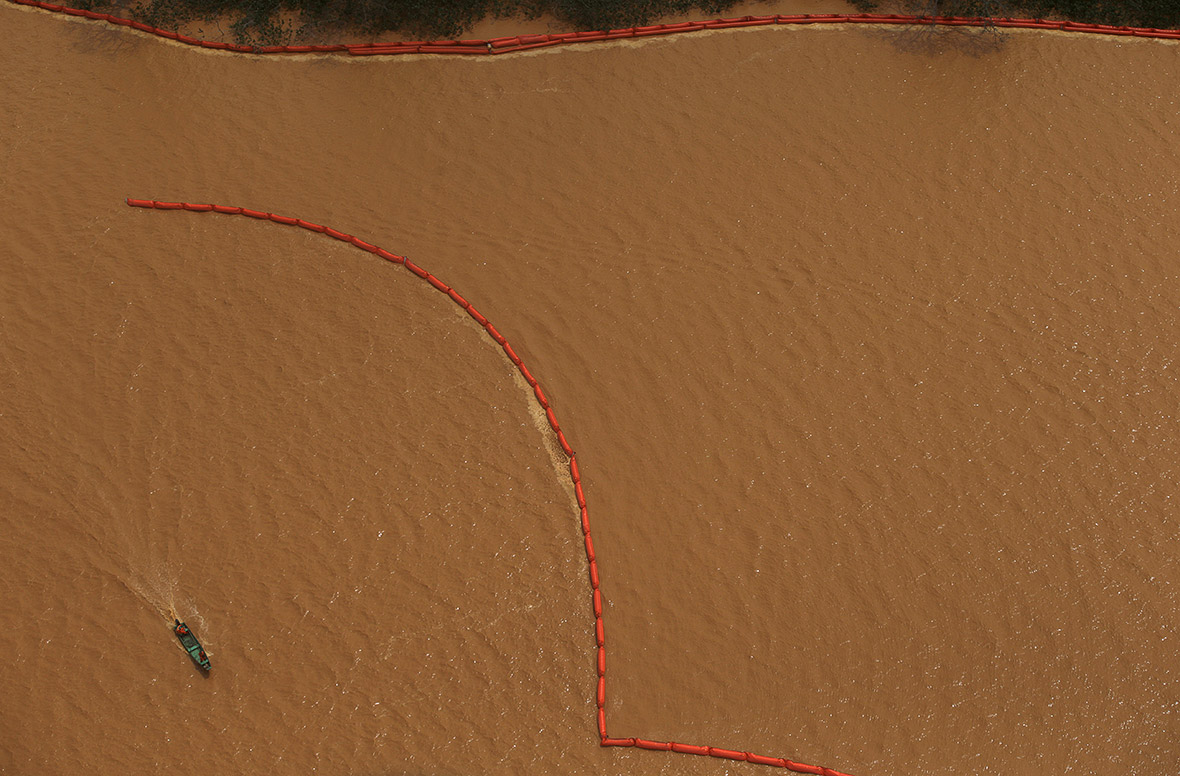

The company has erected nine kilometres of floating barriers in an effort to protect the river bank. The company has also been widening the mouth of the river to allow the mud to flow faster into the ocean, where the toxins will become diluted – after spreading over a much wider area.

Environmental authorities have been documenting the damage and sending reports to federal prosecutors in charge of the case surrounding the burst dams. A spokesman said it was still difficult to determine the extent of the damage, but the mining companies would have to pay for the recovery efforts.

Samarco has agreed to pay a preliminary one billion reais (£177m, $262m) to cover the clean-up costs and compensation – costs the company said already exceeded its insurance cap for civil damages.

It was also fined 250m reais by Brazil's environmental regulator for violations including river pollution and damages to urban areas where water service has been suspended. Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said further penalties from other federal or state agencies could follow.

(Additional reporting: Reuters)

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.