Bubonic plague survived in Europe for centuries between outbreaks, medieval skeletons reveal

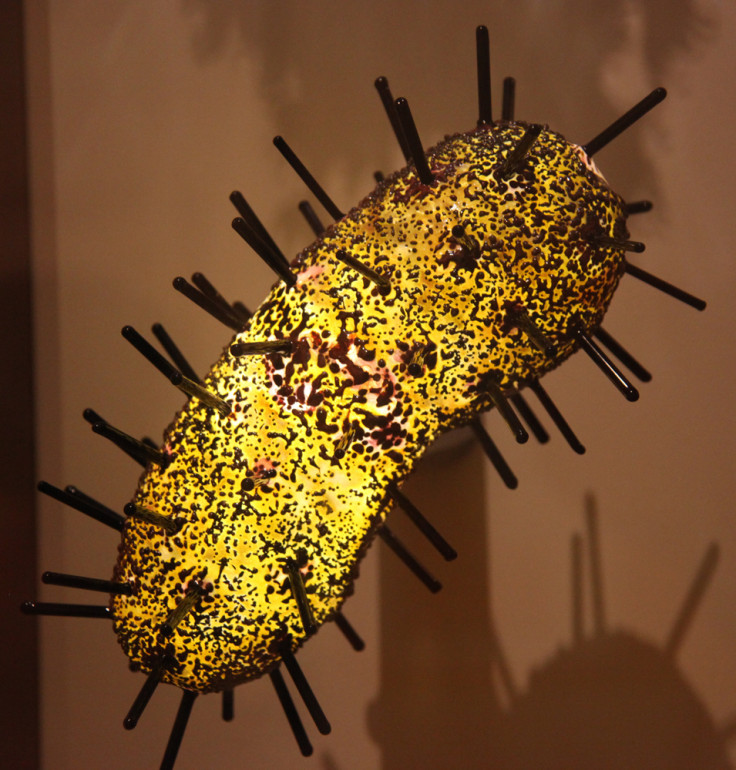

The bacterium which causes the bubonic plague in humans could have been in Europe for a lot longer than previously believed, say researchers. Experts excavated the skeletons of plague victims from as far back as the 14<sup>th Century, and discovered the bacteria, Yersinia pestis, must have survived in Europe for 300 years between outbreaks, in a reservoir which is yet to be found.

The study showed that at least one form (or genotype) of Yersinia pestis persisted in Europe from the 14<sup>th Century until the 17<sup>th Century. Scientists say that this indicates the plague was caused from the same bacterium for both the first outbreak, in the 1340s, and the second in the 1660s.

"The results of the present study clearly indicate that at least one genotype, which was introduced to Europe at the beginning of the Black Death from Asia, persisted in Europe from the 14<sup>th century until the Thirty Years War (1618-1648)," write the researchers, in the study published in PLOS One. "We therefore suggest a model in which Y. pestis was introduced to Europe from Asia in several waves, combined with a long-time persistence of the pathogen in not yet identified reservoirs."

In order to reach their conclusion, the scientists studied the DNA of 30 plague victims. Skeletons were excavated in Germany (Brandenburg and Manching-Pichl), and compared to results from previous investigations from the UK, the Netherlands, and France.

The results showed that eight of the skeletons tested positive for the plague bacterium, and were highly similar to those genotypes from across the continent. In one individual, the DNA extracted from tooth pulp showed infection rates as high as 700 gene copies per microliter – a sign of "severe generalised infection."

This report follows research conducted in 2013 that stated the same bacterium from both plague outbreaks was the same, and a 1,500 year old genome could be determined. The only questioned that remained was how.

"One of, and presumably the most challenging, still unanswered questions concerning both pandemics is how they could have continued for several hundred years," wrote the researchers from the University of Munich. This study answers that question, as at least one reservoir of the bacterium must have existed across the time frame, accompanied by continuous imports from central Asia.

Estimates suggest that as much as 200 million people could have been killed by the bacterium over the course of the outbreaks.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.