Could the US election really be hacked?

The United States presidential election is a complex, drawn-out affair. After months of raucous campaigning at the expense of hundreds of millions of dollars, the lengthy voting process to choose Barack Obama's successor finally got underway with the Iowa caucuses.

Once the two main political parties – Democratic and Republican – choose their respective nominees through party-sponsored contests in each of the states and overseas territories, then it's on to the business of actually electing the 45th President of the United States in November's general election.

But how secure is the all-important process of marking and casting ballots and then collecting and counting them? Could the use of outdated electronic voting systems with dubious safety controls compromise the integrity of the entire electoral process, or is the threat exaggerated?

Unlike a papal election which is entirely manual, 29 out of 50 states in the US make use of direct-recording electronic voting machines (DREs), while 32 states allow voting by the internet for military and overseas voters – methods that are by their very nature susceptible to the type of technological attacks that plague any computing system.

"Unfortunately, they can be quite vulnerable, and this can arise from a number of factors," Andrew Updegrove, an attorney and author who works with organisations to thwart cyberattacks before they occur, told IBTimes UK. He has written a fictional novel on the subject, called The Lafayette Campaign.

Outdated machines

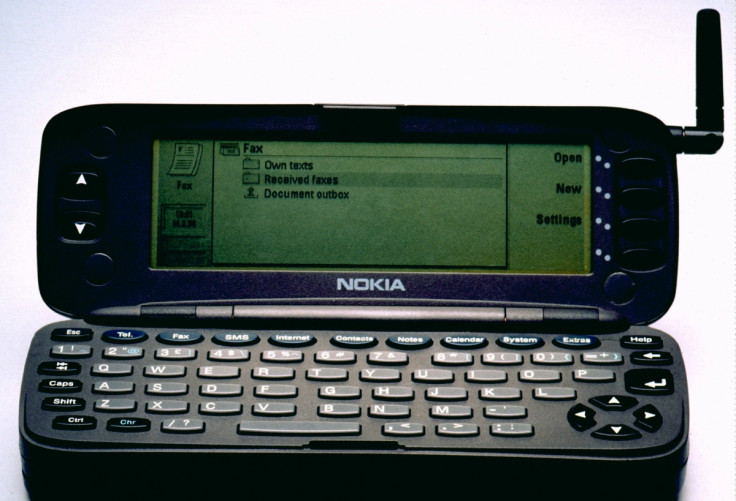

One reason why voting machines are under scrutiny from security experts is their age. Unlike voting systems of previous eras, today's systems were not designed to last for decades. This is because of the brisk pace of technological change – a cutting edge device now may become outdated and obsolete in a couple of years' time.

Think of it this way: You wouldn't expect a laptop or a mobile phone to last a decade, why would a voting machine built in the 1990s be any different?

A recent study by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law found 43 states in the US were using voting machines that were at least a decade old, while 14 states were using devices that were 15 years old.

The report also found that a majority of election officials who believe they need to buy new machines do not have sufficient funding to upgrade their equipment.

Throw in the fact that nearly every state is using a machine that is no longer manufactured – making replacement parts hard to procure – and you are staring into a potent cocktail of security and reliability problems.

WinVote debacle

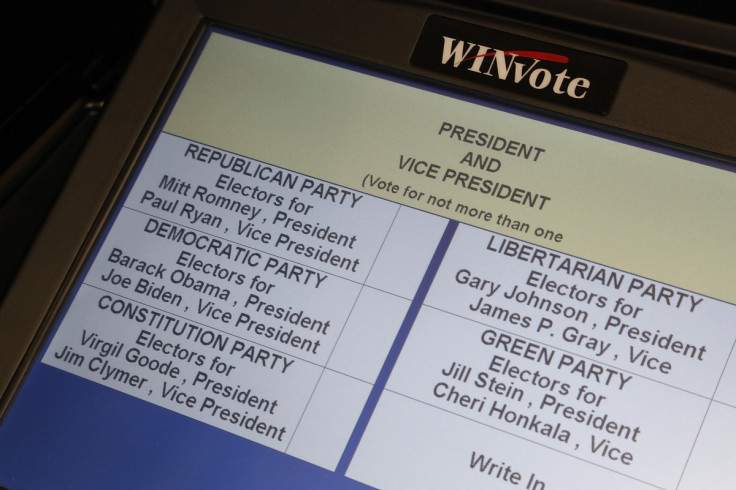

Take for instance voting in the last midterm election in Virginia. In April last year the Virginia State Board of Elections imposed a ban on touchscreen DRE voting, after it emerged that the AVS WinVote machines used in nearly a quarter of its precincts in the 2014 election had gaping security holes.

"If an election was held using the AVS WinVote, and it wasn't hacked, it was only because no one tried," Jeremy Epstein, senior computer scientist at SRI International in Arlington, wrote at the time in a scathing assessment of the voting system.

A state report revealed why. Several WinVote machines, which were used in three presidential elections between 2002 and 2014, were found to be running outdated Windows software and used "abcde" and "admin" as passwords.

The devices were so poorly protected that they could have been hacked undetected from anywhere within a 100-metre radius with a rudimentary antenna built using a Pringles can.

WinVote machines were decertified in Virginia following the damning findings and are no longer in use in other parts of the US.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, Epstein said that several states have moved towards safer optical scanning systems – which involve an optical scanner reading hand-marked paper ballots – since the debacle in Virginia.

"However, many states are still rushing headlong into internet voting, not understanding that they're making the same mistake as was made a decade ago with WinVote – simply taking the word of the vendors that the systems are safe is a recipe for disaster," he warned.

"While I doubt that any of the internet voting systems are quite as bad as WinVote, I have no doubt that the first serious effort to compromise any of them will succeed rapidly and with relatively minimal effort.

"The fact is that scientists and engineers do not know how to build a secure internet voting system, full stop. Anyone who claims otherwise is just wrong – and I say that from a background of 30 years in the security business."

'Vulnerability by design'

Physical security is another area of concern. Voting machines are stored locally, often by towns with tight budgets, making it difficult to put stringent security measures in place.

"That means that they are often easy to tamper with, and it's not possible to create a machine that can't be physically hacked," noted Updegrove.

Hacking a presidential election may seem far-fetched – ludicrous even – but Updegrove argues that it's entirely possible. He cautions that the lessons from the debacle in Virginia have not been learnt and that many of the voting systems that will be used across the US in November lack adequate safeguards.

"When it comes to technology, we're like kids in a candy store – we want the candy now, and we'll worry about the cavities later," he said.

"An apt sales slogan for many companies could be 'vulnerability by design', in part because their customers aren't putting a premium on secure designs, and security is costly. With many of the systems out there, there is no way to audit the machines after-the-fact to determine what votes were actually cast."

Contrast this with paper ballots, where you could always go back to the original ballots in their locked boxes and recount them.

Dire consequences

A successful breach of a voting system can have dire consequences. Hacking just a few electoral districts could enable a malicious group to turn the outcome of an election.

In the 1960 presidential election for instance, John F Kennedy beat Richard Nixon by just one-tenth of a percentage point amid lingering allegations of vote fraud.

And with an election campaign costing hundreds of millions of dollars to run, Updegrove feels there's simply far too much at stake for malicious actors to not make an attempt to influence the outcome.

"With 330 million citizens, isn't it a bit of a stretch to assume that not one of them will decide to spend a few thousand dollars to guarantee that their candidate wins?" he questioned.

"It may be a stretch to assume that it hasn't happened already."

Andrew Updegrove's latest thriller, The Lafayette Campaign: A Tale of Deception and Elections, details the fictional, but technically possible hacking of a presidential election.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.