Deborah Doane: Fashion Revolution Day shines a light on the tragic truth behind our T-shirts

Almost every time a company sells a T-shirt, they're selling a product with blood hidden beneath its seams. It may be the blood of the factory worker who paid with her life, as in the horrific Rana Plaza disaster, or simply living in modern slave-like conditions; it may be on the hands of the farmer who grew the cotton, who tragically took his life because he couldn't make ends meet.

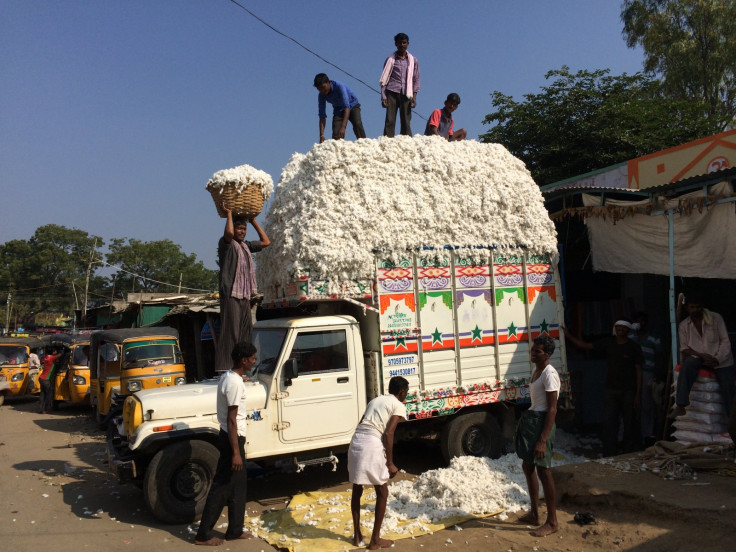

Retailers receive over half the final retail price of cotton products but those who grow the cotton, or participate in the remainder of the complex supply chain – ginning, spinning, weaving, dyeing, stitching – are left to share the other half. Shareholders live the high life while makers and growers pay with their lives.

Fashion Revolution Day on 24 April shines a light on the tragedies that take place at the hands of the fashion sector. We know more about garment workers but the plight of farmers remains almost invisible.

In India, the world's second largest cotton producer, small holder cotton farmers eke out a meagre living. Many have accrued debt to the moneylenders, as each year's costs rise, while income decreases. No longer able to cope with the debt burden – often up to £1,000 per household, and at interest rates up to 48% per year – some choose to take their own lives.

This was the case for Vinay Kumar's father, Macherla Vidyasagar, a farmer from Telengana who committed suicide in 2008, unable to cope with accrued debt repayments after several years of crop failures. The only way he saw out was to go out to his field and drink the very pesticide he was in debt for.

There have been over 285,000 farmer suicides over the past 20 years in India, with nearly 70% occurring in cotton-producing states. These states are generally rain-fed, meaning there is no irrigation to deal with a failing monsoon. Though rains have been consistently poor in recent years, 2014 was particularly bad – at least 30% below the previous year. Meanwhile, prices are collapsing: prices for 2015 are 20% below the year before.

GM fails to offer the solution

GM seeds, once pitched as the solution, may actually be making matters worse. GM ties farmers to expensive seeds, higher input costs, such as pesticides, and over time, especially in rain-fed areas, declining yields. It requires more pesticides, not less, often resulting in health problems among farmers and long-term nutrient depletion in the soil. In spite of this, 95% of cotton grown in India is GM. Organic farmers, meanwhile, struggle to get access to affordable, good-quality seeds.

Organic cotton farmers, such as those who partner with Chetna Organic Farmers Association, fair better. Chetna helps farmers build collectives in order to ensure access to good-quality, non-GM seeds, while helping to encourage small irrigation systems and better cultivation, as well as promoting Fairtrade. Its costs are higher but their farmers are not in distress.

Tragically, the ending of one's life for others relieves nothing. The burden only becomes worse as the debt continues for those left behind. In Vinay's case, he and his mother Poolamma continue to bear the brunt of the sorrow. "Even today the money lenders catch hold of my son and abuse him to repay the loan," says Poolamma. Vinay finds it hard to see the way forward, stating, half-jokingly: "If the situation continues, I might have to take my father's way out."

Fairtrade estimates a 10% increase in the price of seed cotton would go a long way to improving the livelihoods of cotton farmers – a negligible amount on the final price of the fast-fashion T-shirt, often tossed into the back of the closet after a single wearing.

But there's more to do beyond price. The invisible faces behind the clothes are people, with hopes and dreams much like our own. They want to send their children to school, put a roof over their heads and look forward to spending time with their families.

Brands have a strong role to play: they can make longer-term commitments to farmers so they know what price they'll receive and how much they might sell the next year.

They can source from Fairtrade organic cotton farmers. And they can stop cutting costs and returning any and all value to shareholders at the expense of people's livelihoods.

Governments have a role to play: they can provide farmers with insurance and invest in supporting ecologically friendly methods of farming so that farmers don't have to resort to expensive seeds. They can ensure access to affordable credit and curb aggressive marketing by seed companies.

And consumers have a role to play: in being aware of the fact that not only did someone make the T-shirt they're wearing – someone grew it too. They can seek out brands that treat the people who grew and stitched our clothes with the greatest of respect and dignity.

Cotton is integral to the lives of millions of farmers, such as Vinay and his family, as well as workers across the world – its use should be enhancing their lives, not bring endless suffering.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.