Duterte vows to continue war on drugs: 'Addicts and dealers have two choices: jail or hell'

Thousands of suspects have died during the anti-drug campaign he launched after being sworn into office in June 2016, sparking widespread criticism.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has vowed to continue his deadly war on drugs and warns that addicts and dealers have two choices: jail or hell. He said no amount of criticism or international pressure would deter him.

Delivering his annual State of the Nation address, Duterte said his critics at home and abroad should focus on using their influence to educate Filipinos of the ills of illicit drugs. "The fight will be unremitting as it will be unrelenting," he said. "There is a jungle out there, there are beasts out there preying on the innocent, the helpless."

Thousands of suspects have perished during the anti-drug campaign he launched after being sworn into office in June 2016, sparking widespread criticism and threats of prosecution. "Do not try to scare me with prison or the International Court of Justice," he said. "I'm willing to go to prison for the rest of my life."

During his election campaign, Duterte promised to rid the country of illegal drugs in three to six months and repeatedly threatened traffickers with death. But he missed his deadline and later declared he would fight the menace until his last day in office.

More than 5,200 suspects have died so far, including more than 3,000 in reported gun battles with police and more than 2,000 others in drug-related attacks by motorcycle-riding masked gunmen and other assaults, police said. Human rights groups have reported a higher death toll and called for an independent investigation of Duterte's possible role in the violence.

When then-President Barack Obama, along with European Union and UN rights officials, raised alarm over the mounting deaths from the crackdown, Duterte lashed out at them, once telling Obama to "go to hell." Duterte's fiercest critic at home, Senator Leila del Lima, was detained in February on drug charges she said were baseless.

Duterte "has unleashed a human rights calamity on the Philippines in his first year in office," US-based Human Rights Watch said. In April, a lawyer filed a complaint of crimes against humanity against Duterte and other officials in connection with the drug killings before the International Criminal Court. An impeachment complaint against the president was dismissed in the House of Representatives, which is dominated by Duterte's allies.

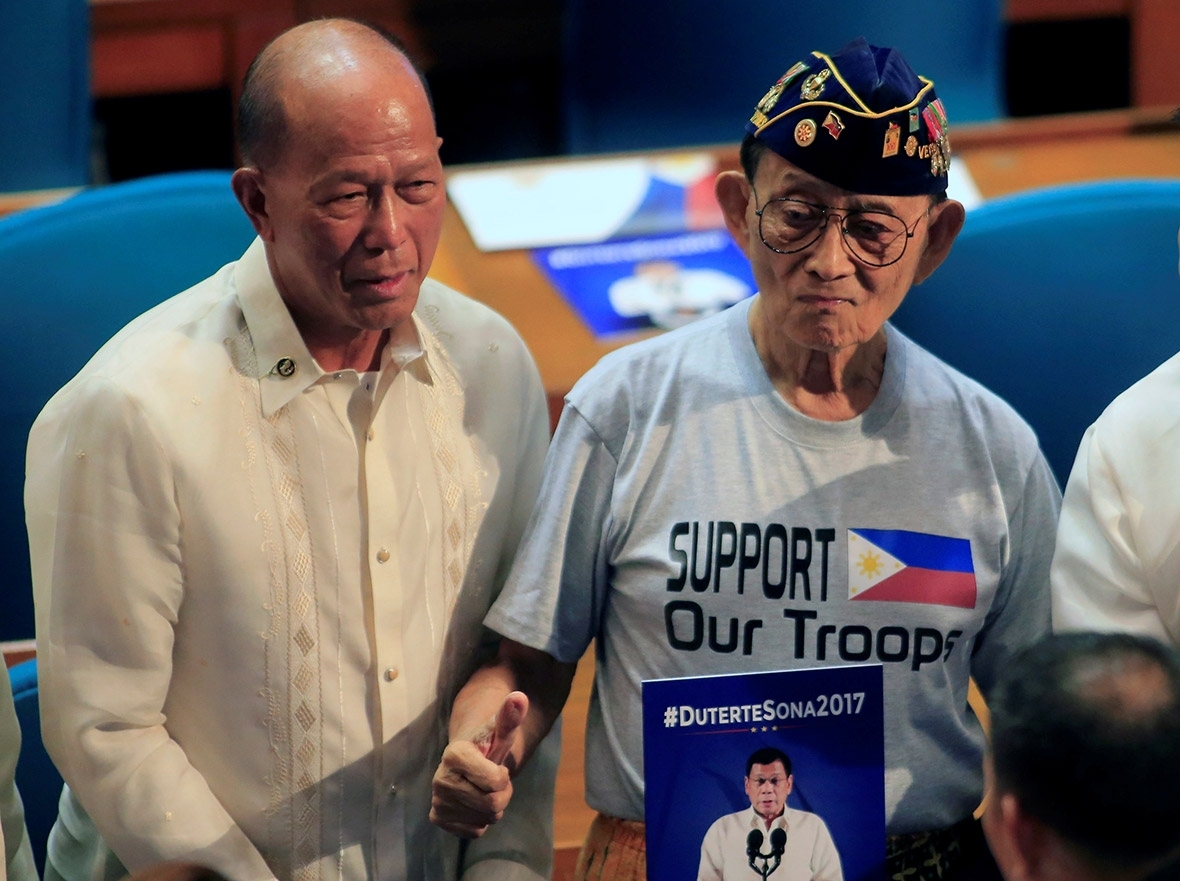

He reiterated his plea that Congress reimpose the death penalty for drug offenders and others. "The fight will not stop until those who deal in (drugs) understand that they have to stop because the alternatives are either jail or hell," Duterte said, to applause from his national police chief, Ronald del Rosa, and other supporters in the audience.

Outside the House of Representatives, thousands of left-wing demonstrators marched with effigies of Duterte to protest against the extension of martial law in the south. They also demanded he deliver on promises made in his first State of the Nation speech last year, including holding peace talks with communist insurgents and improving internet speed.

Riot police, without batons and shields to underscore a policy of maximum tolerance toward demonstrators, separated the protesters from a smaller group of Duterte supporters outside the heavily guarded building.

Duterte won congressional approval for an extension of martial law in the south to deal with the siege of Marawi by pro-Isis militants, the worst crisis he has faced since taking power last year.

Two months after more than 600 pro-Islamic State group militants blasted their way into southern city of Marawi, the military is still fighting the last gunmen — fewer than 100, about 10 of them foreign — in the last three occupied villages.

Congress overwhelmingly voted to grant Duterte's request to extend martial law in the south to the year's end to allow Duterte to deal with the Marawi crisis, and stamp out other extremist groups across the south, something five presidents before him have failed to do.

About half a million people have been displaced by the fighting, some of whom have threatened to march back to the still-besieged city to escape the squalor in overcrowded evacuation camps in nearby towns. Rebuilding Marawi will require massive funds and national focus and will be fraught with pitfalls.

Amid the despair and gargantuan rebuilding, it's important "to ensure that extremist teachings do not find fertile ground," said Sidney Jones, director of the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.