Egypt terror attack sends country back to state of emergency

Activists fear it signals a return to the oppression of the pre-Arab Spring era

Egypt's Parliament has approved a state of emergency, sparking renewed fears the country will return to a police state.

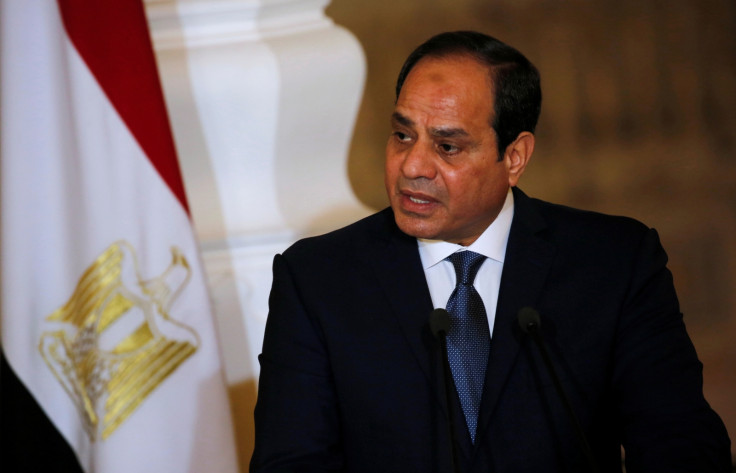

The measure was proposed by Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in the wake of bombings at two Coptic churches on Palm Sunday (9 April), which killed at least 45 people.

The suicide attack, since claimed by the Islamic State (Isis), has sent shockwaves through the Coptic Christian community, which has been increasingly targeted by militants.

Sisi's proposal was unanimously approved by the country's parliament on Tuesday (11 April) and will last for three months.

Addressing Parliament, Egypt's Prime Minister Sherif Ismail said the state of emergency was necessary to combat what he described as terrorist groups bent on undermining the country.

"The emergency law is aimed at enemies of the homeland and citizens, and it will grant state apparatuses greater ability, flexibility, and speed to confront an evil enemy that has not hesitated to kill and wreak havoc without justification or discrimination," he said, reported Reuters.

Hosni Mubarak, the dictator who ruled the country for 30 years, operated a state of emergency throughout his reign to ruthlessly crush any opposition, until he was overthrown in 2011 during the country's revolution.

Under a new constitution, it was then demanded that a state of emergency could only be imposed if approved by Parliament.

Rights activists now believe Sisi is exploiting Sunday's terror attack to unleash his own form of repression.

Nasser Amin, head of an Egyptian-run organisation working to advance judicial independence, told Reuters: "By implementing the state of emergency, almost all the guarantees that exist for rights and freedoms in the constitution will be halted."

The law gives the government the power to halt demonstrations, monitor private communication, disrupt media outlets and close companies.

The Arab Network for Human Rights Information said the law would "further suppress freedom of opinion, expression and belief, and to crack down on human rights defenders".

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.