Genetic infertility: New method can help men with too many sex chromosomes have babies

Abnormalities of sex chromosomes are the most common genetic cause of infertility.

Scientists have developed a new approach to overcome a major cause of genetic infertility – sex chromosome disorders. Tested in mice, it has led to the birth of healthy offspring from previously infertile animals.

Our sex is determined by our sex chromosomes. Girls typically have two X chromosomes (XX) while boys have one X and one Y (XY). However, some individuals are born with an extra sex chromosome which can be problematic if they decide to have children.

"Abnormalities of sex chromosomes are the most common genetic cause of infertility and include conditions such as Turners syndrome, where a female has only one X chromosome (XO) and Klinefelter syndrome where a male has an extra X chromosome (XXY)," Joyce Harper, Professor of Human Genetics and Embryology at University College London, who was not involved with the research, explained.

It is estimated that about 1 in 500 boys are born with an extra X or Y which can disrupt the production of mature sperm and render them infertile.

In a study now published in the journal Science, researchers have shown that it may be possible to remove the extra sex chromosome to produce fertile offspring. Indeed, reprogramming cells carrying a third sex chromosome led to the loss of the extra chromosome in mice as well as in human cells.

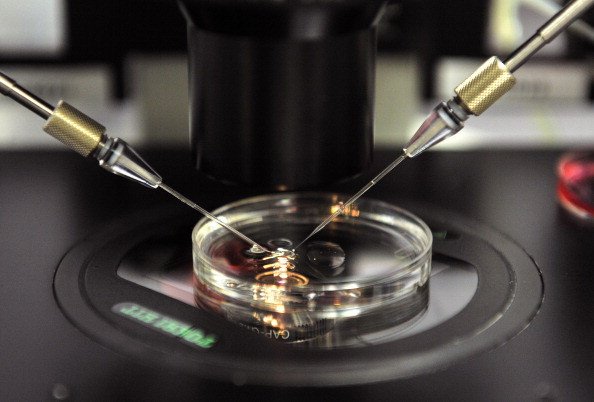

The team took fragments of ear tissue from XXY and XYY mice and cultured them. They were then able to collect fibroblasts - connective tissue cells. Reprogramming these cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), they observed that some lost the extra sex chromosome.

Next, the scientists used a chemical signal to allow these stem cells to specialise into sperm cells. Finally, their injected these stem cells into mice testes, and the animals were able to produce fertile live offspring.

Preliminary experiments were also conducted with the cells of men with Klinefelter syndrome, showing that reprogramming them into stem cells also led to the loss of the extra sex chromosome.

The hope is that this approach will one day be used to treat infertile men with Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) or Double Y syndrome (though infertility is less common in this case) to have children through assisted reproduction.

But these are still the very early days, and a lot more research will have to be conducted in the lab before it can be used as a fertility treatment.

"Our most pressing challenge, which is not possible at present, will be to succeed in converting human stem cells into sperm in a dish. Even if we succeeded in doing this, there would still be the question of whether they work in assisted reproduction. There will be questions about the clinical application but also legal and ethical questions," senior author James Turner, Group Leader at the Francis Crick Institute, told IBTimes UK.

Although the mice born with the technique were healthy, there are concerns for the human children that would be born as a result.

"The use of iPSC to produce sperm and children is not applicable safely in human clinical. At present, it appears to be dangerous. The transplantation of the reprogrammed cells would indeed expose the patients to develop tumours called teratomas, although we are working on the development of human in vitro spermatogenesis which would avoid transplanting reprogrammed sperm cells into the men," Hervé Lejeune from the department of reproductive medicine at Lyon's University Hospital (France), who was not involved in the study, said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.