Has 'Fireball' malware infected 250 million computers? Microsoft disputes shocking claim

Check Point said 'Fireball' could cause 'a global catastrophe'. Microsoft hit back.

On 1 June, cybersecurity firm Check Point warned a strain of malware dubbed "Fireball" had infected more than 250 million Windows computers across the world and had the power to "initiate a global catastrophe." This week (22 June), Microsoft publicly disputed the findings.

Fireball could seemingly take control of web browsers, spy on internet activities and steal personal files. Check Point claimed the operation was linked to a Chinese firm called Rafotech that was allegedly using it to manipulate search engines and scoop up users' private information.

"How severe is it? Try to imagine a pesticide armed with a nuclear bomb. Yes, it can do the job, but it can also do much more," Check Point wrote in its analysis.

"Many threat actors would like to have even a fraction of Rafotech's power," it added.

Now, in a fresh update, Windows Defender Research expert Hamish O'Dea has confirmed that Microsoft has long-tracked the same malware family.

He released internal statistics indicating that – far from 250 million computers – the true infection rate from Fireball has never surpassed five million.

"When recent reports of the Fireball cybersecurity threat [...] were presented as a new discovery, our teams knew differently because we have been tracking this threat since 2015," he wrote.

"While the threat is real, the reported magnitude of its reach might have been overblown."

The blog post added: "In [its] report, Check Point estimated the size of the Fireball malware based on the number of visits to the search pages, and not through collection of endpoint device data. Not every machine that visits one of these sites is infected with malware."

Microsoft said Fireball malware has evolved over the years, and like Check Point, found it spreads via "software bundling" – meaning it's often installed alongside "clean" software. This is a relatively sophisticated tactic, used in an attempt to evade detection by anti-virus software.

"In almost three years of tracking this group of threats and the additional malware they install, we have observed that its components are designed to either persist on an infected machine, monetise via advertising, or hijack browser search and home page settings," O'Dea wrote.

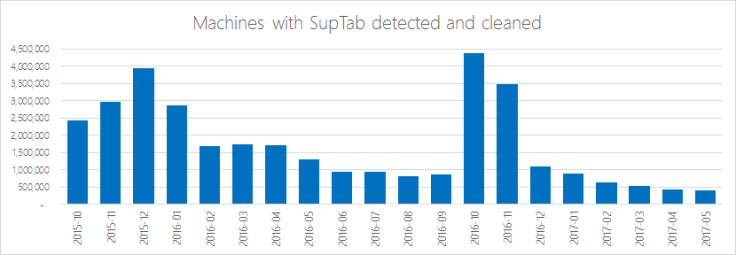

The Microsoft researcher said two prevalent variants in the Fireball suite are called "SupTab" and "Sasquor". The team backed up its assertions based on intel from 300 million Windows Defender clients and monthly scans of more than 500 million machines since October 2016.

In one example, the results showed a clear decline in the level of infections:

You can see the full analysis here.

Microsoft said it had contacted Check Point to request a closer look at its raw data and stressed that its Edge browser is not affected by the browser-hijacking techniques used by Fireball.

"Keeping tabs on the movement of cybersecurity threats, understanding the size and scope of attacks, and disrupting cybercriminal campaigns through next-gen technologies are fundamental parts of our day-to-day work at Microsoft Windows Defender Research," O'Dea stated.

IBTimes UK contacted Check Point for further insight into the case however had recieved no response at the time of publication.

"We tried to reassess the number of infections, and from recent data we know for sure that numbers are at least 40 million, but could be much more," Maya Horowitz, Check Point's threat intelligence group manager told CNet in a statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.