Low-cost ketamine can be used to treat severe depression, according to study

According to a recent study from the University of New South Wales, a low-cost version of ketamine has been shown to effectively treat severe depression.

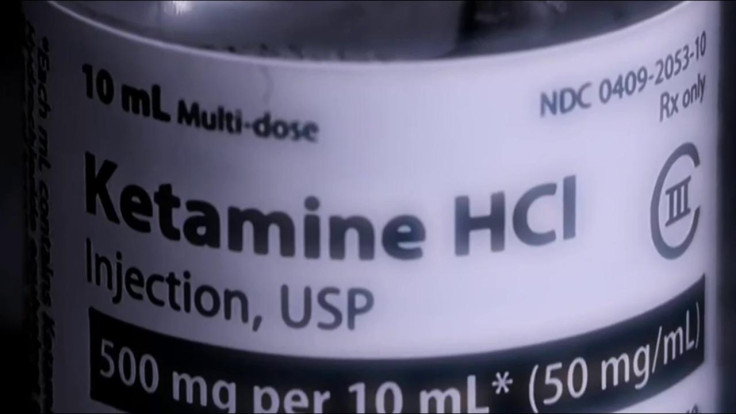

Ketamine is a highly potent form of medication that doctors will commonly use as an anaesthetic to induce a loss of consciousness – the drug can also be applied for recreational use.

However, as is the case with most drugs, ketamine can prove to be extremely harmful, and even fatal, if used irresponsibly and mixed with other Class A drugs.

For decades, smaller doses of ketamine have been used for anaesthetic purposes, but in more recent times, it has been used as a treatment for pain, depression and even for people with autism. In terms of depressive treatments, there have been various studies examining the impact that ketamine has on improving mental health.

In a recent study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, researchers led by the Black Dog Institute and UNSW Sydney, a public university in Australia, created a double-blind trial that involved prescribing generic ketamine to 179 participants with treatment-resistant depression.

However, unbeknownst to the participants, approximately half of them were in fact given a placebo instead of generic ketamine.

Lead researcher, Professor Colleen Loo, said: "We found that in this trial, ketamine was clearly better than the placebo, with 20 per cent reporting they no longer had clinical depression compared with only two per cent in the placebo group."

Professor Loo didn't fail to mention that "20 per cent remission is actually quite good".

To conduct the study, all of the participants received two injections per week (placebo or ketamine) in a clinic where they could be closely monitored for around two hours until the sedative effects wore off, which usually occurred within the first hour. This treatment lasted for a month, with the participants being asked to assess their general mood at the end of the trial.

As this was a double-blind trial, neither the participants nor the researchers administering the drug were aware of which patients were given ketamine or a placebo; this was primarily to ensure that psychological biases were minimised. Additionally, in order to mask the differing treatment, the placebo that was used was midazolam, which also causes sedative effects.

The study generated positive results, with one of the standout findings being that using the generic ketamine for treatment-resistant depression proved to be much cheaper than the S-ketamine nasal spray currently in use around Australia.

To put it into perspective, the patented S-ketamine nasal sprays currently cost around $800 per dose, whereas the generic ketamine dosage comes to a fraction of that price, costing as little as, believe it or not, a mere $5. Although patients would still need to pay for the medical care on top of the drug, it would still cost significantly less than the S-ketamine nasal sprays.

Professor Loo commented on the price, saying: "With the S-ketamine nasal spray, you are out of pocket by about $1,200 for every treatment by the time you pay for the drug and the procedure, whereas for generic ketamine, you're paying around $300-350 for the treatment including the drug cost."

"It's quite cost-effective when you see how incredibly quickly and powerfully it works. We've seen people go back to work, or study, or leave hospital because of this treatment in a matter of weeks," Professor Loo concluded.

The researchers announced that they will be looking to create larger trials to assess the effects of generic ketamine over a much longer period, whilst safely monitoring all participants' treatment.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.