Migrant crisis: Frustrations boil over as refugees face long wait on Greek island of Lesbos [Photo report]

Thousands of migrants and refugees are facing despair, anger and frustration on Lesbos. After perilous sea voyages from neighbouring Turkey, they have been stranded on the scenic Greek island for days, some for nearly two weeks. Many are running out of money, all are desperate to get to mainland Greece and continue their journey to western Europe.

Lesbos, normally home to 100,000 people, has been transformed by the sudden influx of some 20,000 refugees and migrants, mostly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. The strain is pushing everyone to the limit.

Fights break out among the people as they are kept waiting in long queues for hours in the summer heat and humidity. The small police force, overwhelmed by the numbers, charges in at any sign of trouble, beating crowds with batons to break them up.

"We escaped from ruin to be met with more ruin here," said Mohammed Salama, a 45-year-old Syrian. He fled the Damascus suburbs where fighting has raged for years, seeking a refuge so he can bring his four daughters and pregnant wife who remained behind. "I did not come here to make money," he told the Associated Press. "I came here so I can later bring my children and have them live in safety."

Lesbos is one of several Greek islands hugging the Turkish coast that are the first stop for many of those trying to reach western Europe.

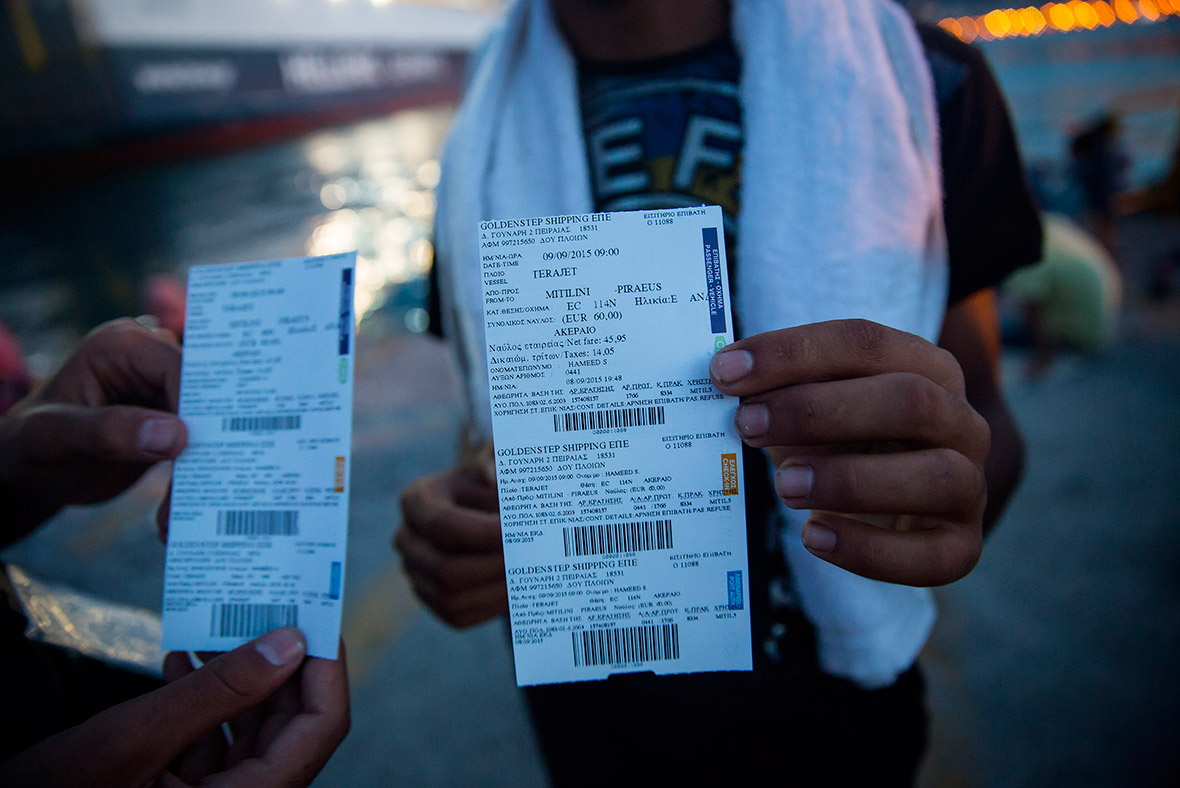

On Lesbos, they must register with police and receive an official document. Without that document, they can't buy a ferry ticket to the mainland to continue on land through the Balkans. But the registration offices are swamped, slowing everything down.

Under the punishing sun in high humidity, hundreds crowd outside the offices for hours. Brawls break out frequently among the hot, exhausted crowds.

The nerves of many Lesbos residents are fraying. Drivers blast their horns in fury at migrants and refugees walking in the middle of the streets near Mytilene's port. There are also acts of courtesy and kindness. Some restaurants let in women and children to use their bathrooms. Policemen sometimes help the elderly, offering them seats, and when there are no tensions, they quietly answer the migrants' countless questions about their fate.

Among the refugees and migrants, confusion reigns. Lines suddenly form and people rush to join them and wait for hours, only to discover the line was sparked by a rumour and they were waiting for nothing. On Saturday (5 September) a crowd converged on one of the prefab caravans that serve as registration offices by the port. Afghans and Syrians fought for position in the queue, until police rushed in. It turned out the caravan was empty.

Class and sectarian divisions show, according to an AP reporter. Most of the Afghans are impoverished men in their 20s, while the Syrians and Iraqis include families and the middle class. Most of the Afghans are from their country's Shi'ite minority, a point several of the mainly Sunni Muslim Syrians, coming from a bloody war with sectarian overtones, bitterly mention.

The day for most migrants and refugees begins at sunrise, as they converge on the registration offices, but the day drags on with queues, scuffles, confusion and exhaustion and despair set in. Infants cry constantly. Parents try to comfort children sobbing from thirst or hunger.

Two or three times a day, a ferry arrives, and those who have received their documents and bought tickets rush to the port. Each ferry carries about 2,000 people to the port of Piraeus near Athens.

In the evening, those still waiting search the streets for pieces of cardboard to sleep on. Camps have been set up outside Mytilene, but few want to use them because they want to stay near the port.

At least 850,000 people are expected to cross the Mediterranean seeking refuge in Europe this year and next, the UN said, giving estimates that already look conservative. UNHCR (the UN refugee agency) called for more cohesive asylum policies to deal with the growing numbers. Four million Syrians are registered as refugees in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. Another eight million are displaced within Syria itself.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.