Mobile Wars: Qualcomm's actions may have led to the death of WiMax

FTC says Qualcomm has unfair patent licensing policies and made deals with Apple that harmed competitors.

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is suing Qualcomm for alleged unfair patent licensing policies that harmed competitors by illegally forcing them out of the market. The semiconductor manufacturer is also in trouble for entering into exclusive deals with Apple, such as allegedly bribing it not to make a WiMax iPhone.

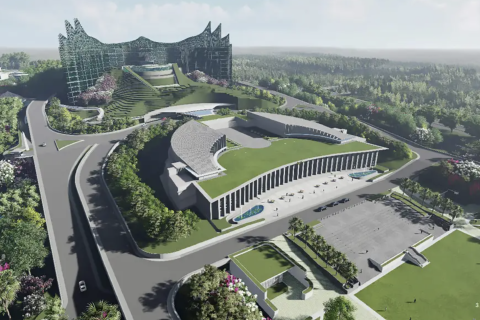

WiMax was a wireless technology that was meant to be used to build 4G networks. It was first formally defined as a standard in 2001 and was heavily backed by semiconductor manufacturer Intel and infrastructure provider Cisco. WiMax was designed to provide 30-40Mbps mobile data speeds, and eventually in 2011 the standard was updated to provide speeds of up to 1Gbps.

Initially WiMax did really well – mobile operators in 148 countries were deploying fixed line and mobile networks using the technology by October 2010, but then from 2011 onwards, there was a sharp decline in WiMax usage.

Even though WiMax networks were already in existence and it offered fast mobile data speeds, it became much cheaper for mobile operators to upgrade their 3G networks, rather than building a whole new network using WiMax, which used a new type of technology that could be used to provide broadband internet as well as mobile internet.

Although having WiMax would mean that mobile operators could then offer both mobile internet and regular broadband services as a sort of "universal internet", they wouldn't be able to compete with low prices offered by existing DSL and cable broadband providers, so mobile operators decided to pick the cheaper option to get to 4G.

Suddenly operators all over the world were switching to back an alternative 4G technology called LTE instead, and WiMax's popularity fell even further when no WiMax smartphones appeared on the market. No WiMax phones meant no consumers were using it to access mobile internet – they were still using the old 3G networks, which were fast running out of bandwidth.

Qualcomm asked Apple not to make WiMAX iPhones

This is where Qualcomm comes in. The semiconductor manufacturer was strongly opposed to WiMax, and according to the FTC, may have actively helped to kill off the standard by convincing Apple, the biggest smartphone manufacturer in the world, not to build phones that worked on the standard.

"Apple has negotiated with Qualcomm in an effort to reduce the royalty burden that Apple bears through its contract manufacturers. As a result of these negotiations, Apple entered into agreements with Qualcomm in 2007, 2011, and 2013," the FTC's lawyers write in the redacted complaint.

"Under a 2007 agreement, Qualcomm agreed to rebate to Apple royalties that Qualcomm received from Apple's contract manufacturers in excess of a specified per-handset cap. Qualcomm's payment obligations were conditioned upon, among other things, Apple not selling or licensing a handset implementing the WiMax standard, a prospective fourth-generation cellular standard championed by Intel and opposed by Qualcomm."

The FTC also claims that Qualcomm made life incredibly difficult for other processor manufacturers by persuading Apple to sign an agreement ensuring that Apple only put Qualcomm chips into its products over a five-year period from 2011 to 2016.

Bullying "no licence, no chips" policy

The FTC complaint references Qualcomm's 'no licence, no chips' policy. Smartphone manufacturers need baseband processors in order to build smartphones, because the chip is the core of smartphones that control all its functions. However, it seems that if a manufacturer wanted Qualcomm to sell it the chips, it would also have to agree to purchase expensive licences for patents relating to established mobile standards.

Forcing people to buy things they don't need in order to get something they do want is a violation of fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) licensing terms set out by the FTC. However Apple agreed to sign the agreement because Qualcomm promised to give it a discount on the licence royalties.

If Apple decided anytime in the five-year period to use another manufacturer's chips in its products instead, then the agreement meant Apple would have to back pay Qualcomm the full value of the licence payments from October 2011 onwards.

"Several former competitors of Qualcomm have sold off or shuttered their baseband processor businesses, unable to achieve the sales volumes and margins needed to sustain a viable business...if Qualcomm's remaining competitors were to exit the business as a result of Qualcomm's anticompetitive conduct, this would have a significant adverse impact on competition in baseband processor markets and on innovation," FTC concludes, asking the court to stop Qualcomm from engaging in any further unlawful conduct.

"Enhanced innovation in mobile technologies would offer substantial consumer benefits, especially as these technologies expand to new applications, including extending mobile connectivity to consumer appliances, vehicles, buildings, and other products (the 'Internet of Things'). By suppressing innovation, Qualcomm's anticompetitive practices threaten these benefits.

"Qualcomm's practices have harmed competition and consumers both within the markets for CDMA and premium LTE baseband processors and in other baseband processor markets in which OEMs pay Qualcomm inflated royalties. These include markets for UMTScompliant baseband processors and lower-tier LTE baseband processors."

Qualcomm has issued a statement refuting the FTC's complaint.

"This is an extremely disappointing decision to rush to file a complaint on the eve of Chairwoman Ramirez's departure and the transition to a new Administration, which reflects a sharp break from FTC practice," said Don Rosenberg, executive vice president and general counsel, Qualcomm Incorporated.

"In our recent discussions with the FTC, it became apparent that it still lacked basic information about the industry and was instead relying on inaccurate information and presumptions. In fact, Qualcomm was still receiving requests for information from the agency that would be necessary to an informed view of the facts when it became apparent that the FTC was driving to file a complaint before the transition to the new Administration. We have grave concerns about the two Commissioners' decision to bring this case despite a lack of evidence supporting the allegations and theories in the complaint. We look forward to defending our business in federal court, where we are confident we will prevail on the merits."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.