Nasa's new X3 ion thruster engine could carry humans to deep space

X3 has been designed by researchers at the University of Michigan in collaboration with Nasa and the US Air Force.

Nasa has been working on a plasma engine and their latest one has broken records in terms of power and thrust. Dubbed the X3 thruster, the latest development in technology might make it possible for the space agency to scale it up to useful levels soon and many hope that the this could be used to ferry humans to deep space.

The technology is on the right track to enable its use in full-sized, manned space missions in less than 20 years, reports Space.com. X3 was designed by researchers at the University of Michigan in collaboration with Nasa and the US Air Force, says the report.

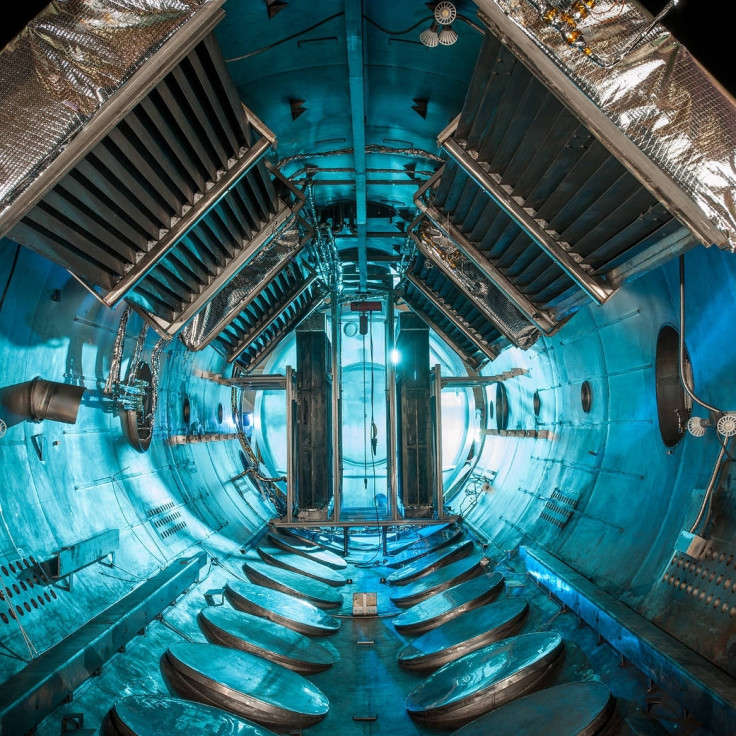

The X3 is a Hall thruster, a type of ion thruster that creates propulsion by firing a stream of electrically charged atoms, called plasma, out of a nozzle. The electricity used to achieve this could come from solar panels. A recent demonstration of the X3 at Nasa's Glenn Research Center reportedly broke several records.

Apart from using electricity to generate thrust, this engine of the future could also potentially accelerate spacecraft to higher speeds than chemical propulsion rockets. This is one of the main reasons why there is so much research around this type of engine.

Chemically fuelled engines using liquid oxygen and hydrogen, for example, can reach a maximum velocity of about 5km per second, Hall thrusters, on the other hand, could reach 40km per second, says the report.

Alec Gallimore, who heads the research and is also the dean of engineering at the University of Michigan told Space.com, "We have shown that X3 can operate at over 100 kW of power.". "It operated at a huge range of power from 5 kW to 102 kW, with electrical current of up to 260 amperes. It generated 5.4 Newtons of thrust, which is the highest level of thrust achieved by any plasma thruster to date."

Plasma engines are also a lot more efficient with much better miles per gallon ratio, says Gallimore. "You can think of electric propulsion as having 10 times the miles per gallon compared to chemical propulsion," he said.

The drawback, as of now, with ion-thrusters, is that we are yet to reach the level of technology to scale it up to useful levels. "Chemical propulsion systems can generate millions of kilowatts of power, while the existing electrical systems only achieve 3 to 4 kilowatts," Gallimore said. What is needed is a system that can create 20 to 40 times the power that they are able to generate in the lab.

In the coming years, the team will be carrying out more tests on the X3, namely running it at full blast for 100 hours as a test of reliability. The idea is to build an engine that can operate at maximum power for several years, continuously.