New brain mapping reveals individual changes linked to different mental illness

A breakthrough brain mapping project involving patients diagnosed with different types of mental illness has revealed a startling diversity in brain changes.

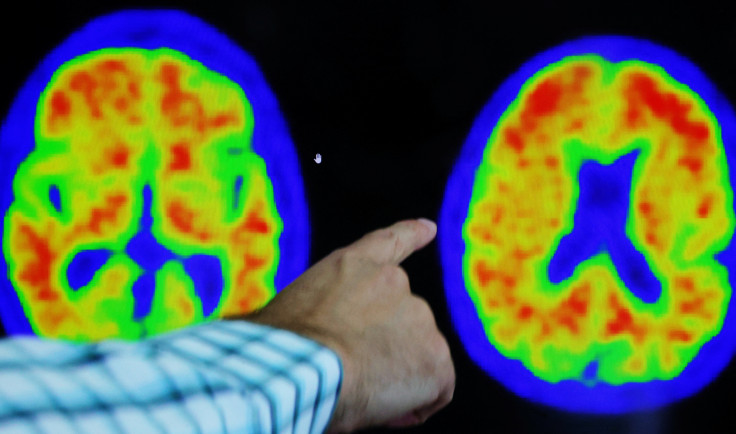

Over the past few decades, brain mapping has been a common procedure for the way clinicians treat patients with various mental health disorders.

By measuring electrical activity, clinicians are able to evaluate various functions within the brain, whether they be independent or moving together.

From this process, the clinicians are able to pinpoint which frequencies within the brain are off balance. Evidently, with this information, they can create personalised programmes to help their patients overcome their troubles with mental health.

There are a wide variety of mental health disorders that can hugely benefit from brain mapping including depression, ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and anxiety disorder.

But now, in a breakthrough brain mapping project that involved nearly 1,300 patients diagnosed with six different types of mental illness, researchers have found an extraordinary diversity of brain changes found in people with major depression and schizophrenia.

The study was led by researchers at Monash University's Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health and the School of Psychological Sciences in Melbourne, Australia.

To conduct this study, researchers used extensive brain imaging to measure the size and volume of over 1,000 different brain regions.

Ms Ashlea Segal, a PhD student and leader of the study, stated: "Over the past few decades, researchers have mapped brain areas showing reduced volume in people diagnosed with a wide variety of mental illness, but this work has largely focused on group averages".

"For example, knowing that the average height of the Australian population is about 1.7 m tells me very little about the height of my next-door neighbour," Segal continued.

The research team used new statistical techniques developed by Professor Andre Marquand, who also co-led the project, at the Donders Institute in the Netherlands.

These techniques allowed the team to map regions in the brain that showed unusually small or large volumes in people diagnosed with either schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder or diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder.

According to research team leader, Professor Alex Fornito, he stated: "We used a statistical model to establish expectations about brain size given someone's age and sex."

He continued saying: "We can then quantify how much an individual person's brain volume deviates from these expectations, much like the growth charts commonly used for height and weight in paediatrics."

The team at Monash University then investigated the general connectivity of the areas in the brain that show the largest volume deviations.

Citing the brain as a network, Segal explained that dysfunction in one region can spread to affect others, even the connected ones.

Incidentally, her team found that while deviations occurred in distinct regions across different people, they were often connected to common upstream or downstream areas, meaning that they aggregated within the same brain circuits.

Ms Segal believed that this overlap could explain commonalities between people with the same diagnosis. For example, why do two people with schizophrenia have more symptoms in common than a person with schizophrenia and one with depression?

The team ultimately leveraged their new approach to identify potential treatment targets for different disorders. However, the targets suggest that these targets will only be appropriate for a subset of people.

Regardless, and going forward, this approach developed by the team does open up new opportunities for mapping brain changes in mental illness.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.