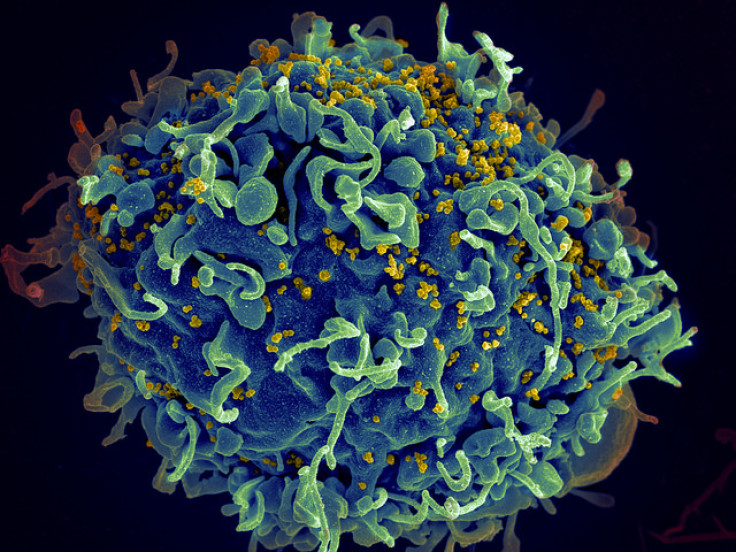

New HIV antibody neutralises 99% of strains and prevents infection in monkeys

At present there is no vaccine for HIV.

A new genetically engineered antibody that neutralises 99% of HIV strains in early trials has been developed by researchers.

Natural antibodies are a type of immune cell found inside the body that attack bacteria and viruses.

While those that occur naturally tend to target one part of a virus, the genetically engineered versions – called tri-specific antibodies – attack three key parts of HIV. Early experiments suggest that this makes them highly effective in suppressing its growth and reducing the chances of subsequent infection.

The ground-breaking study, published in the journal Science, was the product of a collaboration between scientists from the US National Institutes of Health and the Paris-based pharmaceutical company Sanofi.

"Unlike natural antibodies, 'tri-specific' antibodies engage multiple targets in a single product. This approach to multi-targeting provides an opportunity to improve protection against HIV and represents a foundation for potential new treatments of cancer, immune, and infectious diseases," said Gary Nabel, Chief Scientific Officer and Senior Vice President of Sanofi, and a lead author of the study.

One of the main challenges when it comes to tackling HIV is the virus's ability to mutate into different strains inside a patient, making it very hard for the immune system to defend itself.

However, some long-term HIV patients develop powerful defences called 'broadly neutralising antibodies', which researchers have been trying to harness to treat the disease or even prevent infection in the first place.

Now, the new research has combined three of these 'broadly neutralising antibodies' into a far more potent weapon – the so-called 'tri-specific' antibody.

This new treatment has the highest breadth of coverage yet seen against the virus, neutralising 99% of more than 200 diverse strains.

Furthermore, the researchers gave the new antibodies to 24 monkeys and later injected them with the HIV virus. None of the animals developed an infection suggesting that the treatment could potentially be effective in preventing the virus from taking hold in humans.

At present, there is no vaccine for HIV.

It is important to note that the new technique in question is still in its infancy and its safety and effectiveness have not been evaluated by any regulatory agency. Clinical trials are set to begin next year.

"Combination therapy has already demonstrated its value in HIV and cancer therapy. Tri-specific antibodies represent a potential new class of therapeutics that can block multiple targets with a single agent", said Nabel.

Linda-Gail Bekker, president of the International AIDS Society, added: "We know antibodies are an important component of the human natural defence system against a host of diseases including infections. Sometimes these natural antibodies aren't sufficient to hold diseases in check – HIV is a good example of this."

"This breakthrough opens the potential that protective antibodies can be engineered in such a way that they are super powered to be even more effective than the natural antibodies. It is early yet and so we will need to see how safe and how well they work in human clinical trials before we know what the full potential for public health could be."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.