Nuclear fusion: Max Planck's Stellarator produces first hydrogen plasma – watch live online

The Wendelstein 7-X "Stellarator" at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics is set to produce its first hydrogen plasma. The experiment will hopefully edge us a little closer to achieving nuclear fusion – limitless and cheap energy that is sustainable.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has been invited to switch on the first hydrogen plasma at a ceremony that will be livestreamed from the institute. You can watch the event live online from 2.45pm CET (1.45pm GMT). The countdown to the switch on will begin at 3.35pm CET.

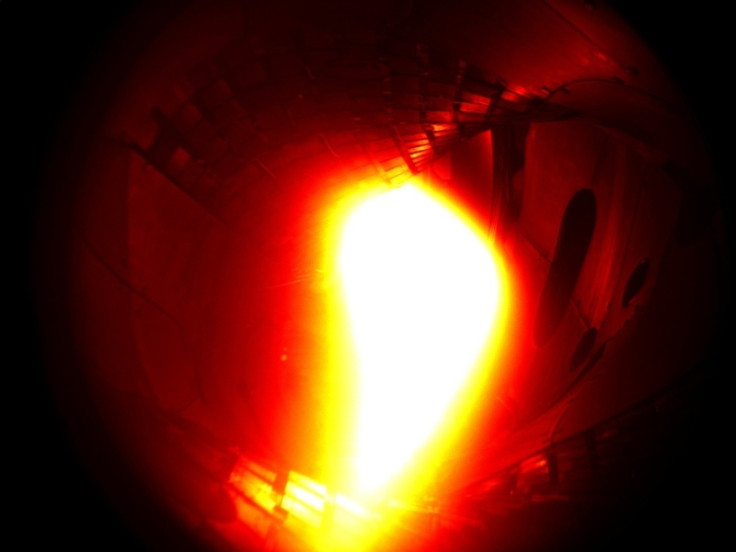

The switch on marks the start of scientific operation at the Wendelstein 7-X. Successful tests on the machine – which took nine years to build – took place in December. "This, the world's largest and most modern fusion device of the stellarator type, has already been working since the beginning of December 2015 with a helium plasma as preparation for the first hydrogen plasma," the institute said in a statement. "The objective of fusion research is to derive energy from fusion of atomic nuclei just as the Sun does."

Nuclear fusion is the goal of many researchers across the globe. It would work in a similar way to how the Sun harvests energy by fusing atoms together. However, to get energy, gas from deuterium and tritium has to be heated to one million degrees Celsius. This has so far proven impossible.

Another issue is that plasma cannot come into contact with the cold wall of vessels, so it must be suspended in mid-air somehow. The Wendelstein 7-X will show how plasma can be suspended in a stellarator, meaning they are suitable for use in a power plant. Tests in December 2015 showed the first plasma achieved temperatures of around one million degrees Celsius. This was not hydrogen plasma, though.

Speaking at the time, project leader Thomas Klinger said: "We're starting with a plasma produced from the noble gas helium. We're not changing over to the actual investigation object, a hydrogen plasma, until next year. This is because it's easier to achieve the plasma state with helium. In addition, we can clean the surface of the plasma vessel with helium plasmas."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.