Pulseless bionic heart: Successful sheep transplant will lead to human trials in 2018

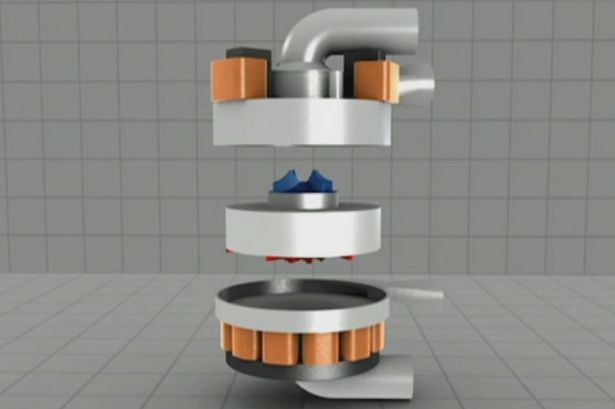

The world's first bionic heart without a pulse has been successfully tested in a healthy sheep and is set for human trials within three years. The ground-breaking device, developed by scientists at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, replaces a pulse action with a spinning disc that pumps blood around the body.

This is a significant departure from previous bionic heart designs, which favour cumbersome balloon-like sacks to mimic the action of a biological heart.

"There were other devices that were quite large, and they also would break quite easily," said Daniel Timms, the lead designer of the device.

"And the reason they would break is they would have a sack, so if you're beating them billions of times per year, they're going to break."

The device designed by Timms, known as a BiVACOR, is predicted to last 10 years longer than previous designs as it uses magnetic levitation to prevent wear and tear on components.

The complete transplant of a sheep's heart for the BiVACOR was undertaken by a team of surgeons from Australia and the US.

"There was no native heart at all," said John Fraser from the Prince Charles Hospital in Queensland. "Instead, there was a titanium disc spinning, keeping this sheep happy and healthy. It was a fantastic team effort."

In order to move towards human trials, a crowdfunding campaign has been set up on the site The Common Good, with the hope of raising around £2.5m ($3.8m) to fast track development.

"We've now shown that the device works. This idea is viable. Now it's a matter of making it robust and reliable so that it works in a patient," Timms said. "The time frame is three to five years before it could be ready for humans. We need to test it for a year to confirm its safety and regulatory properties before we implant it in a patient.

"Proving the concept was the first real hurdle. There are many to go from here but we're confident we have the collaborative team to take it to that next level."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.