Read Watership Down as an adult – it's so much more than a children's story

None of Adams' later books came close to its success, but my neighbour's great epic had true authenticity.

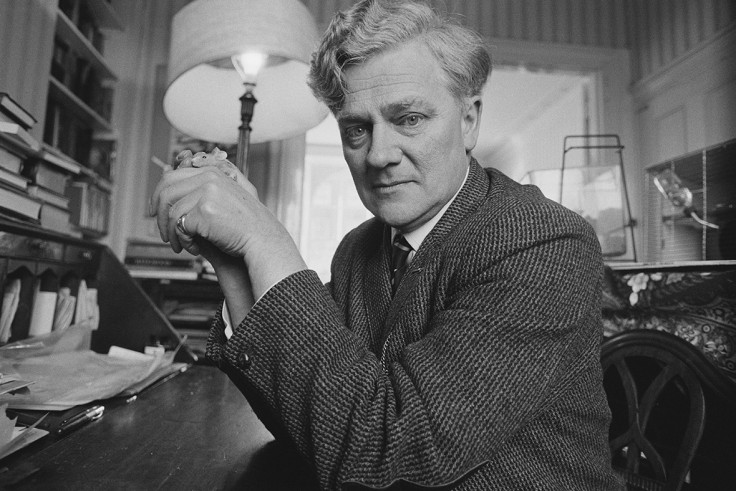

"The primroses were over". What an English way to start a novel: restrained, wistful, laconic. And indeed the author of those words, Richard Adams, who has just died, was a very English figure. When he promoted his books abroad, he wore a bowler hat and carried his own mustard and marmalade with him.

His opening line made no impression on me when I read Watership Down at the age of nine. Now, I almost choke up at its melancholy.

If you last read Adams's magnum opus in childhood, you will remember it as a gripping adventure involving rabbits. But if you have read it as an adult (as I recently did to my daughters) you'll have found yourself reciting a hymn of praise to England's countryside. Indeed, you'll wonder how you ever thought of it as a children's story at all. Listen, to pluck an example more or less at random, to this passage:

When we think of the downs, we think of the downs in daylight, as with think of a rabbit with its fur on. Stubbs may have envisaged the skeleton inside the horse, but most of us do not: and we do not usually envisage the downs without daylight, even though the light is not a part of the down itself as the hide is part of the horse itself. We take daylight for granted. But moonlight is another matter. It is inconstant. When it comes, it transforms. It falls upon the banks and the grass, separating one long blade from another; turning a drift of brown, frosted leaves from a single heap to innumerable flashing fragments; or glimmering lengthways along wet twigs as though light itself were ductile. Its long beams pour, white and sharp, between the trunks of trees, their clarity fading as they recede into the powdery, misty distance of beech woods at night.

I live on those downs. For those who know the story, the warren of Efrafa lies at the opposite end of the field that stretches from my front door. Richard Adams lived in the same parish. He gave a talk at one of our local bookshops last year, aged 95, and mused about whether he might have a go another novel.

In fact, none of his later books came close to the success of Watership Down. Shardik was a grim fantasy involving a giant bear worshipped as a deity; the eponymous Plague Dogs had fled from a scientific research facility. Both novels were deftly plotted, but neither approached the popularity of the lapine odyssey.

What was so special about Watership Down? It comes down to authenticity. Adams was 52 when he wrote the great epic – an unusually late age for a writer's creativity to peak. He was condensing a lifetime's affection for these broad, sloping chalk fields into his work, and luxuriated in the opportunity to describe them from a different perspective. Once you have looked at these weeds and wildflowers from a rabbits'-eye view, you'll never see them the same way again.

There is something else, though. Adams was writing in 1971 as a veteran whose wartime service had largely been forgotten. There are novels about the First World War, in which First World War doesn't appear: novels such as Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises, Evelyn Waugh's Vile Bodies, F Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (excepting two glancing references) and arguably even JRR Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Watership Down is an example of something rarer: a book about the Second World War in which the Second World War doesn't appear.

There is one conscious reference: a story-within-the-story when the mythical rabbit hero El-Ahrairah returns home after fighting to redeem his people only to find that the younger generation don't want to hear about his exploits. Yet a semi-military flavour infuses most chapters. The protagonists are an all-male group who make up what is, in effect, a platoon. Their interactions and their idiom are soldierly. Yet they are unwilling warriors, forced by circumstance from their former lives. The story of Hazel, Fiver and their companions is that of Adams and his generation – the story of a people who were martial but never militaristic.

Many fans have responded to the author's death by quoting the line his rabbits intone when one of them passes: "My heart has joined the Thousand, for my friend stopped running today". Yet Adams gives us better death-poetry than that. Let me instead close with a stanza recited by the fey rabbit Silverweed.

In autumn the leaves come blowing, yellow and brown.

They rustle in the ditches, they tug and hang on the hedge.

Where are you going, leaves? Far, far away

Into the earth we go, with the rain and the berries.

Take me, leaves, O take me on your dark journey.

I will go with you, I will be rabbit-of-the-leaves,

In the deep places of the earth, the earth and the rabbit.

Daniel Hannan has been Conservative MEP for the South East of England since 1999, and is Secretary-General of the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists Follow : @danieljhannan

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.