Robots could move more like humans with these soft, 3D-printed synthetic muscles

The 'muscle' is made of silicone rubber and can be controlled with a resistive wire.

A team of engineers from the Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Sciences have developed a synthetic muscle that can operate without actuators, compressed air, or pressure regulators.

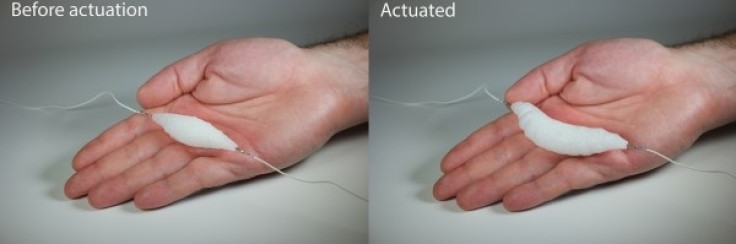

According to a Futurism report, the material can lift 1,000 times its own weight and can be made with a 3D printer and even has 15 times more strain density when compared to natural muscle.

While robots require a lot of equipment to regulate movement, especially when they rely on pneumatic and hydraulic inflation, such components take up a lot of space and add to the weight. This is one of the reasons why, according to the report, small machines that can operate on their own is difficult to create.

However, the new "muscle" that was developed is made of a silicone rubber matrix with microbubbles of ethanol infused within them and when a low power charge is passed through a thin resistive wire, it actuates, says the report.

In a press release from the university, Hod Lipson - who is the professor of mechanical engineering and also leads the research - has pointed out how they have been making great strides toward making robots minds, but robot bodies are still primitive. "This is a big piece of the puzzle and, like biology, the new actuator can be shaped and reshaped a thousand ways. We've overcome one of the final barriers to making life-like robots."

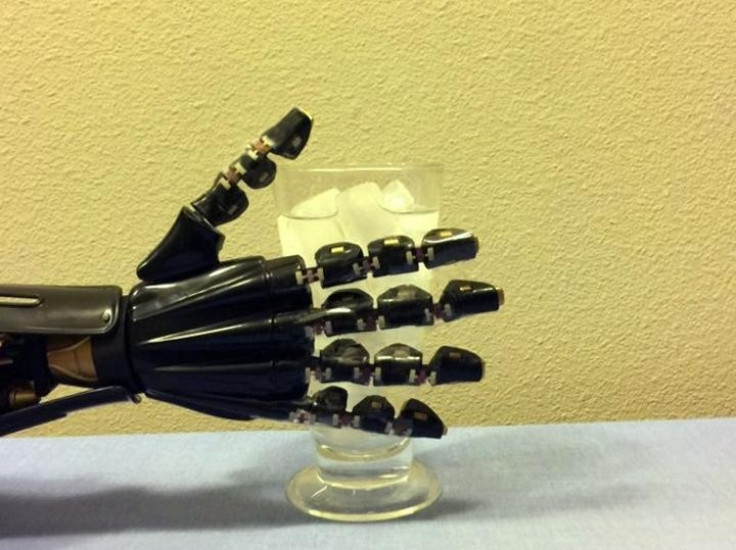

Robots that require a certain level of finesse and dexterity when handling certain objects have been difficult to build and this material could help create a robot that can grip and hold objects without damaging it.

According to the report, a soft touch would be required in certain situations and delicate assistance from robots could be needed places like hospitals and other medical settings. Another field where this material could prove to be useful is medical prosthetics. With a lifelike feel and touch, makers of prosthetics could build in improvements in control that users would need from robotic limbs.

The report also points out that researchers are now looking to replace the resistive wire with conductive material which they believe would shorten the muscle's response time. They are also looking to have artificial intelligence control the muscle's movements, giving it a more enhanced, human-like, and purposeful movement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.