Scientists Find Way to Boost Memory of Dementia, Alzheimer's Patients

Scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles, have found a way to improve the memory of people suffering from dementia or early Alzheimer's disease.

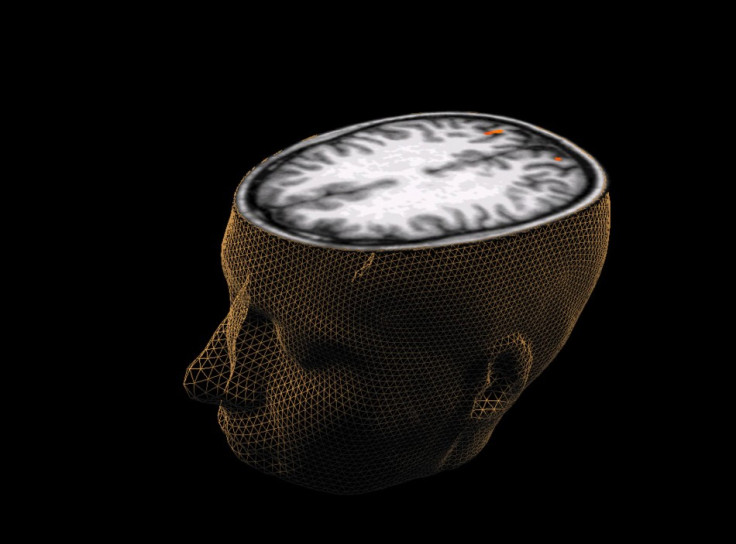

Scientists had conducted an experiment on a key site called entorhinal cortex in the brain. The entorhinal cortex helps in forming and storing memories. It plays a crucial role in transforming daily experience into lasting memories. By triggering the entorhinal cortex with a slight electric shock one can regain one's memory.

During the experiment, the researchers had implanted electrodes into the patient's brain. Patients were asked to play a virtual video; they played the role of cab drivers who picked up passengers and travelled across town to deliver them to one of six requested shops.

During the virtual trips, patients could not recognize landmarks and navigated the routes very clearly. After some time the patients were given a slight electric shock into the entorhinal cortex. Researchers then asked the patients to play back the game. Now surprisingly, they could easily recognize landmarks and navigated the routes more quickly and they even learned to take shortcuts, reflecting improved spatial memory. This happened because the electric shock had activated the entorhinal cortex.

Scientists are planning to study deep-brain stimulation to find out if it can even enhance other types of recall, such as verbal and autobiographical memories.

Six million Americans and 30 million people worldwide are diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease each year. The progressive disorder is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States.

"The entorhinal cortex is the golden gate to the brain's memory mainframe," said Dr. Itzhak Fried, a professor of neurosurgery at the University of California, Los Angeles. "Every visual and sensory experience that we eventually commit to memory funnels through that doorway to the hippocampus. Our brain cells must send signals through this hub in order to form memories that we can later consciously recall."

"When we stimulated the nerve fibers in the patients' entorhinal cortex during learning, they later recognized landmarks and navigated the routes more quickly," he said.

"They even learned to take shortcuts, reflecting improved spatial memory," he added.

"Losing our ability to remember recent events and form new memories is one of the most dreaded afflictions of the human condition," he added.

"Our preliminary results provide evidence supporting a possible mechanism for enhancing memory, particularly as people age or suffer from early dementia. At the same time, we studied a small sample of patients, so our results should be interpreted with caution," he added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.