Stefan Stern: Amazon employees find themselves at the mercy of big data

"Scientific management", a concept developed and popularised by the American engineer FW Taylor over a century ago, has efficiency and productivity at its heart. Taylor's epiphany was that manufacturing processes could be analysed and broken down into easily repeatable parts. The spirit of Adam Smith, and his idea of the division of labour, were brought into the industrial age, at scale. Time and motion were vital factors to be managed carefully. Clipboards, stopwatches and early management consultants were the outward symbols of this way of seeing the world.

Nobody is against efficiency. But taken to extremes this approach can limit what your business is capable of producing. Well-trained and educated employees can do more than simply repeat basic tasks over and over again. Indeed, to carry out truly valuable work clever staff need some autonomy. They need time and space to think. That is why most creative (and successful) businesses have moved on from crude Taylorism to something a bit more grown-up.

But not, according to some reports, Amazon, where the micro-measurement and management of staff continues at pace. It is not just the warehouse fetchers and carriers who are monitored at every step (literally). Managers too are often expected to be on-call almost continuously, regardless of time zone or family commitments. A recent feature in the New York Times offered a troubling picture of unsympathetic bosses and a culture that is both cruel and unforgiving.

And successful! The company, from whom you can buy almost anything and have it delivered speedily, is a stock market champion, even if it is still not actually, you know, profitable (the company did unusually show a small profit of $92m in the last quarter, which came as a surprise). But at over $500 a share, with revenue heading for $100bn annually, the company has a market cap of nearly $250bn. These are problems most companies would like to have.

In terms of reputation, as well, the latest brouhaha does not seem to have done Amazon too much harm. Research carried out by alva, the corporate reputation monitoring business, suggests that concerns over Amazon's approach to paying tax or its standard of service have had a bigger impact on its reputation than stories about workplace practices.

"While the media has been strongly critical of Amazon, the data shows it is unlikely to move the majority of investors or consumers to change their relationship with the company," alva says. The bigger risk lies with employees and potential future employees.

"Looking at Glassdoor's rating trends for Amazon shows a gradual decline in employee satisfaction at the company over the past few days," alva reports, "following on from a steep decline seen around the 'tax avoidance' period. Employee 'recommendations to a friend' are also at an industry-low level of 63%, well behind Google on 92%, Facebook on 88% and Microsoft on 81%."

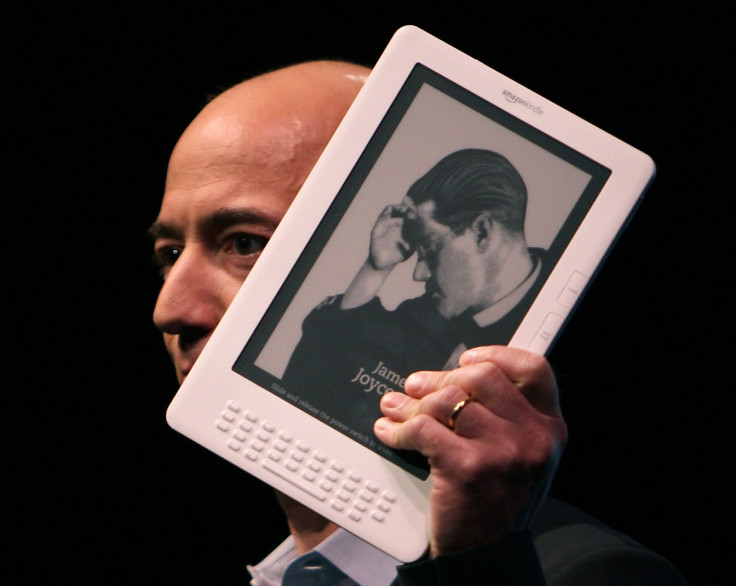

If enough key people decided that they had to leave for the sake of their physical and mental health the company would have a problem. This partly explains the very nice salaries on offer to senior people there. The rapid response from chief executive Jeff Bezos to the New York Times story showed that Amazon was aware of its vulnerability on this point. But it won't have been enough to calm fears about life on the shopfloor. Nor will the words of its senior vice president for global affairs (and former White House spokesman), Jay Carney – "This is an incredibly compelling pace to work" –reassure everyone.

Bezos and his business have always been "full-on". Amazon has never pretended otherwise. The company has an innovative approach to using data. It invites robust feedback from all, and promotes "challenge". This works for them – or at least for the senior people who choose to stay. It may not be entirely sustainable, however, as Bezos' note to staff (and the world) seemed to concede.

Data is everywhere, and good managers will want to use it to help them run their businesses better and in a timely manner. An annual appraisal is a miserable thing, too slow to encourage change at the speed it is required. And yet: see what you make of this vision of the future of management, from Michael Distefano, chief marketing officer at executive recruitment firm Korn Ferry in Los Angeles, as reported by Business Insider:

"I envision a world where we've all got wearables on and you send a pulse survey to a few hundred employees a day asking about different levels of engagement: 'Here are four emoticons, which one best depicts how you feel about your job?' That gets transmitted to a dashboard, and the first thing a CEO does in the morning is grab his tablet, plug into the dashboard, see how people are feeling, and make a few calls accordingly."

If you're like me you might find all this slightly absurd and slightly chilling. But if you like the sound of it maybe you should send your CV to Jeff Bezos.

Stefan Stern is a business, management and politics writer. He writes for The Guardian and The Financial Times and is a visiting professor at Cass Business School.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.