Stefan Stern: Put people before sales and profits to get investors to sit up and take note

One of the less obvious perils of a career in business is the tendency for people to forget how to speak their own language. With familiarity comes cliché and not long after that, the cessation of original thought.

That is the explanation, if not the excuse, for the repeated assertion that "our people are our greatest asset". This phrase has been used for years by business leaders who may have thought they meant it, even if they did not really know what it implied. It just sounded like the right thing to say. Everybody nodded and we moved on.

In fact, there has not been too much wrong with the management talk over the years. The problem has been the lack of the right sort of action.

Employees get disillusioned pretty fast when they are told they are a great asset one day and then receive miserable treatment the next. If managers acted as though people really were valued, this could all be very different. That is one reason to applaud a new body of research supported by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

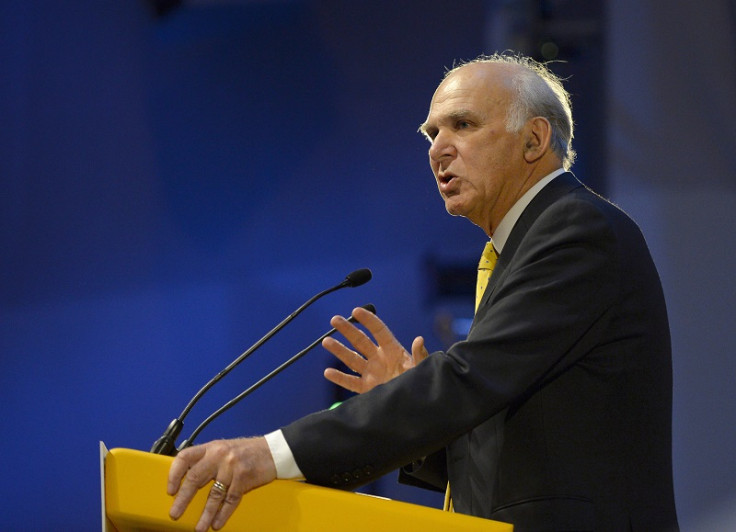

Last summer, Anthony Hesketh, a senior lecturer at Lancaster University Management School, published "Managing the value of your talent: a new framework for human capital measurement". And last week, a group of partner organisations met at Unilever's London headquarters to promote a new "Valuing your talent" campaign. Vince Cable, the secretary of state for business, innovation and skills, also attended and made a few supportive remarks.

Here is an opportunity to make some of that other fine talk – about the exciting new world of data – mean something too. Hesketh shows how better measurement of what people are doing at work – "human capital measurement", in the jargon – could be valuable for employers but also, crucially, for investors as well.

How many employees do you actually have?

Wouldn't it be good to know what the levels of staff turnover are at a business, and how much it costs to recruit people? Does the business have momentum – that is, are good people staying or leaving? Sophisticated investors, Hesketh says, are already tracking the career paths of key executives on boards or in senior management positions and adjust their investment decisions based on whether they stay or move on.

Some other basic measurements will help both managers and investors understand what is going on in the business. How many employees do you actually have? It may sound like an absurdly basic question but it is one many companies struggle to answer. If you don't really know how many staff you have, how can you measure your cost base accurately?

What is the total investment in relevant training and development? How much are you spending and what is the money going on? Bosses ought to know and intelligent investors will want to know.

Lastly, what are your employee engagement scores? This is a disputed concept, and perhaps one that is quite hard to measure reliably, but it can tell you a lot about the prevailing mood in the organisation and how well the business is doing.

Crucially, this sort of measurement can give you advance warning of a company's future prospects. They are lead indicators rather than the purely historic indicators of sales or profits before tax – numbers which, as we all know, can be massaged and manipulated to smooth out any surprises.

Managers ought to want to know what is going on, in human as well as financial terms. Investors should too. Some institutions are waking up to this. As Doug Baillie, formerly a senior operations person at Unilever but now its chief HR officer, says of his meetings with investors: "The really smart analysts spent 10 minutes talking about our business results and 40 to 50 minutes talking about people."

Measuring people's performance is not a new idea, of course. The Kingsmill "accounting for people" report from over a decade ago explored similar territory. But perhaps the financial crisis, and the sense that investors have been flying blind, has given a new impetus to the idea. Greater computing power means data can be gathered, processed and analysed more easily than in the past.

Good management involves paying attention to people. Measuring intelligently what they are doing allows you to manage better. As with so many of the best ideas, this one really is incredibly simple.

Stefan Stern is a business, management and politics writer. He writes for The Guardian and The Financial Times and is a visiting professor at Cass Business School.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.