Super-Earths with atmospheres stripped away by radiation from their stars discovered with Nasa's Kepler

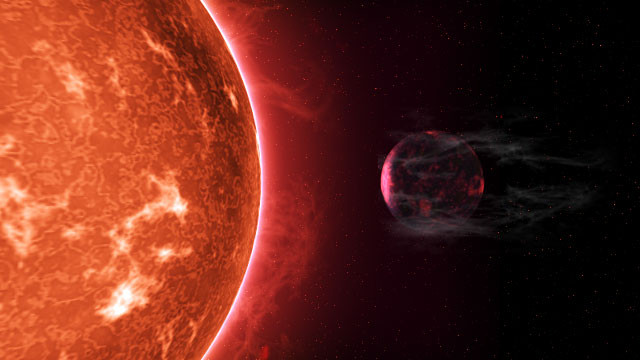

Scientists have discovered a type of exoplanets that lie so close to their host star, that their atmospheres are ripped apart by radiation. The heat from the stars physically blows away the gaseous outer layer of rocky exoplanets, similar to the effect of a hot hairdryer.

The research, published in Nature Communications, will help astronomers to understand how planets evolve over time, and the role their host star plays in that evolution. Previous simulations of these exoplanets orbiting closely to their host star showed their atmosphere being blown away. Up until now though, it had not been seen directly.

Researchers from the University of Birmingham used the Nasa Kepler space telescope to identify these 'super-Earths'. These planets are larger than Earth with a similar make-up, but not as big as the Solar System's ice giants; Uranus and Neptune.

They found that when an exoplanet is within a certain distance from its star, and a particular size, their atmosphere is blown away by radiation. The scientists identified a total of 157 of these "hot-super-Earth deserts".

They observed the planets – all made up of a rocky core, with a gaseous outer layer – being inundated by powerful radiation from their host star. "For these planets, it is like standing next to a hairdryer turned up to its hottest setting," said Guy Davies, a researcher working on the study.

"There has been much theoretical speculation that such planets might be stripped of their atmospheres. We now have the observational evidence to confirm this, which removes any lingering doubt." He added that these planets would probably have been far bigger early on in their existence, and looked very different to how they do now.

This discovery will help scientists model how planetary systems evolve, including our own Solar System. "Our detection of a hot-super-Earth desert will add an important constraint for simulations of the evolution of planetary systems," they wrote.

The researchers plan to investigate more of these systems using data from new satellites, including Nasa's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). The TESS mission, due to launch in 2017, is designed to find exoplanets that orbit bright stars, but are too far away for the Kepler telescope to find.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.