Third Reich for Sale: The Jewish TV Star Who's Cornered the Nazi Memorabilia Market

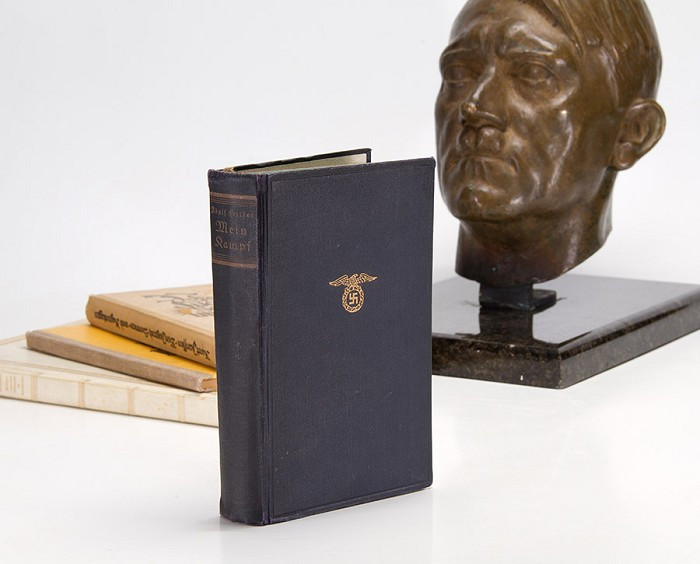

Earlier this month, from a lot in Solana Beach, California, Adolf Hitler's own personal copy of Mein Kampf, arguably the most destructive book in modern history, was auctioned.

The book which outlined the Nazi dictator's political ideology as well as his anti-Semitic views was retrieved from the library in his Munich apartment at the end of the Second World War.

It was just one of a range of items, including Swastika emblazoned weapons, medals and uniforms, from the most notorious regime in history that were sold that day for thousands of dollars on the History Hunter website.

The $28,000 price tag was staggering but fell short of expectations. "[The sale price equated to] half a year's or a year's salary for some people," auctioneer Craig Gottlieb said. "Things went for strong prices, which in an uncertain economy like this is always a positive sign that this particular genre of collectibles is still alive and well."

In Germany, it is illegal to sell items decorated with a Swastika, but in Western Europe and North America the market for so-called Nazi antiquaries thrives and in recent months, auctions of Nazi memorabilia have been stirring enormous controversy.

In France earlier this year, an auction, including items belonging to Nazi Reichsmarschall Herman Goering, was cancelled after Jewish groups accused organisers of "harming the memory of victims of Nazi barbarity".

Nazi sympathisers

Auctions this year of Third Reich memorabilia in London and Washington DC have also drawn criticism, with auctioneers accused of profiting from the promulgation of fascism and collectors of being Nazi sympathisers.

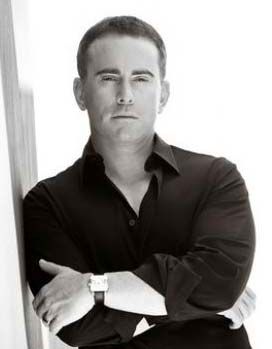

In all this furore it may come as a surprise to learn that Gottlieb, is himself of Jewish descent whose ancestors escaped Jewish Pogroms in Tsarist Russia earlier in 20<sup>th century.

Former marine and Cornell graduate Gottlieb, aged 43, known to many from the History Channel's Pawn Stars, defends his trade. His collectors are simply passionate historians, intrigued by one of the darkest periods of modern history.

"Everyone is fascinated by the Nazis," Gottlieb tells me on the phone from California. "The interest in Nazi militaria antiques is strong, and it has nothing to do with the political message of the Nazis.

The interest in Nazi militaria antiques is strong, and it has nothing to do with the political message of the Nazis

Gottlieb argues that what distinguishes the collector from the average armchair history buff is the means and the will to connect with history directly.

"If you want to go really deep into history you've got to hold a piece of it in your hand," he says. "Love of history is a disease and artefacts are their primary vehicle to connect with that history."

He said that many of his clients insist on keeping their identity secret because of the stigma attached to Nazism, and include a number of celebrities.

"I have customers whose name you'd know, who said 'Craig, assure me that you won't tell anyone that I am collecting this, because it would ruin my career'."

There are even Jewish collectors, he says. "I know one guy whose mother was in a camp, and he even has some of her Jewish material in his collection... her "J" marked passport, for example."

Political religion

As we talk, Gottlieb refers to the fascination with history as a "disease" or an "addiction" and I wonder if for some the interest in the period is something less than salutary.

Historians have described Nazism as a form of political religion, in which rituals and iconography instilled a cult-like loyalty. Is there not a possibility that he is selling to far-right sympathisers, who will use the objects to further Hitler's poisonous legacy?

Gottlieb claims though that he has never turned down a buyer because he suspected they would put an object to the wrong use, and that Neo Nazis have neither the will nor the means to buy the artefacts he offers for sale.

"I am always mindful of someone who is buying this stuff to glorify the political message of Hitler," he says. "But I haven't found that. It just doesn't exist.

"The people in the Neo-Nazi world -- and there are crazies out there -- they aren't buying that kind of stuff because it is too expensive. These kind of people are interested in the message and not the artefact.

"Someone who wants to be a Neo-Nazi does not have to buy a $500 flag. They can buy a $50 flag.

"The kind of stuff I sell goes to historians and history buffs who are fascinated by the Swastika. They aren't in love with it," he says.

Gottlieb argues that without this material coming to market, our understanding of the Holocaust and Nazism would be impoverished as a result.

Most Holocaust museums would simply consign the material to a "dark vault" if it came into their possession, he argues. Few would give anywhere near enough display space to items from the early years of Nazism.

"I would love to work with the Holocaust Museum to build a huge display of Third Reich militaria and regalia, but they are simply not interested. I don't know why. I think it's because they can't get through their brain the legitimacy of preserving these artefacts," he says.

Dark theatre

For Gottlieb, an appreciation of the insignia of Nazism, of its dark theatre, is essential for understanding its appeal and how it was able to turn "butchers, bakers and candlestick makers into concentration camp guards".

"Part of what Hitler did so well is to use physical propaganda as a tool to rise to power. You can look at the fact that his actions led to the deaths of millions of people and you have to say 'how did he do it?' It's one thing to stare into the pits of Auschwitz and say 'oh what a shame it is'. It is a better exercise to say 'why?' and see how they got there."

He draws a contemporary parallel with the iconography of Islamic State, the jihadist group that has spread terror after conquering swaths of Iraq and Syria, and publicly beheading Western hostages.

"Look at Isis with their flag," he tells me. "If I asked you to draw the black flag you may not be able to write Arabic but you could do it. Every army marches under a banner and every movement has a symbol, so we need to be very cognizant of that."

Gottlieb concedes though that there are some items which are better off in public collections.

"The really strong pieces do have a place in the museum," he said. "I sold in a similar auction a gravestone. [One might ask] Why do I have a gravestone? And is it ethical to have one? It was a Jewish gravestone that was recycled in the 1930s, after the famous Nazi digging-up of Jewish graveyards and used for an SS officer. It has Hebrew lettering on one side and SS runes on the other side. Now that is the kind of artefact that needed to be in a museum.

"And it did sell to a museum belonging to an individual on a philanthropic mission similar to my own. I wanted it to go to someone who was going to use it for good reasons."

For some though, museums are the only safe place for this material.

"The issue is 'Who buys it?' 'Who is attracted to buying it?'" Abraham Foxman, president of the Anti-Defamation League, a US-based organisation dedicated to fighting anti-Semitism, told me.

"That is the troubling issue. Once it is on the open market anyone can buy it."

Foxman dismissed as "nonsense" the notion that the public sale of far-right memorabilia gives it a greater public exposure than it would have if bought by a museum or educational establishment.

These places should use them as educational tools rather than objects of macabre fascination and hate

"There are rich bigots and there are poor bigots," he said. "Some bigot is going to buy it [an object offered for sale] and how is that going to help the public? Items from the Holocaust will end up in the library of a far-right sympathiser."

Foxman, though, does not believe that Nazi memorabilia should be banned from sale.

"People have the right to own them. The way to deal with it is not to ban the sale," he says.

There should be a covenant between auctioneers and collectors to ensure that these items go to museums and educational establishments.

"These places should use them as educational tools rather than objects of macabre fascination and hate.

"In museums, they are protected from the intentions of those who want to use it as a way to spread hateful ideologies."

Gottlieb though insists that there is an almost transformative effect to handling these items personally.

"You put something as personal as powerful as Hitler's personal copy of Mein Kampf in their hands, and they go 'oh my God' It effects you when you hold it," he said.

It is probable that some of these items end up in the possession of those fascinated with Nazi Germany for the wrong reasons.

Warped aesthetics

Gottlieb appears genuine when he insists that most artefacts end up with history enthusiasts, some of whom may get a thrill from the warped aesthetics of Nazism, but most of whom have no interest in seeing it established as a political reality.

But it's inevitable that there will be some who seek profit from that fascination, regardless of what society thinks.

However with support for the far-right on the increase across Europe, fascism remains a real danger. Foxman's insistence that it is up to us all to ensure that its powers to seduce the desperate and gullible are never repeated is timely.

It is an issue though that will continue to stir controversy, as many of the war generation die and their relatives cash in on the souvenirs they inherit.

"It's a nice 'bonus' at the end of the road for a veteran to be able to 'cash in' -- and it can mean a lot of money. It's also a chance to relive the most profound months and years of their lives," said Gottlieb.

He predicts that growth in the sector could be huge with the 75<sup>th anniversary of the end of the war next year.

"People realise they could actually own a piece of history. And here's another thing, supply is fixed, they aren't making any more antiques."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.