Twenty years on Final Fantasy 7's biggest problem is still hanging over the iconic series

PS1 classic Final Fantasy 7 celebrates 20th birthday but was not a perfect template for the series.

Final Fantasy 7 is too long. The plot is incomprehensible, characters are somehow both overwritten and under-explored and the emotional beats, rather than loving or melodramatic, are predictable and mawkish. After enjoying, for 20 years, a reputation as a classic, FF7 can take these criticisms – it will remain, in so many people's hearts and minds, a great work.

But the complaints levelled at last year's Final Fantasy 15 - that it was too slow, that the characters were thin and that keeping track merely of what was going on, when confronted with so many narrative and interactive tangents, was close to impossible - relate also to its beloved, PS1-era predecessor.

If knocking Final Fantasy 7 seems spiteful or contrary, that's evidence of how the game's mythology rather than its substance is what has survived in our minds. Surely anyone who played the game, particularly nowadays, would feel comfortable acknowledging its faults.

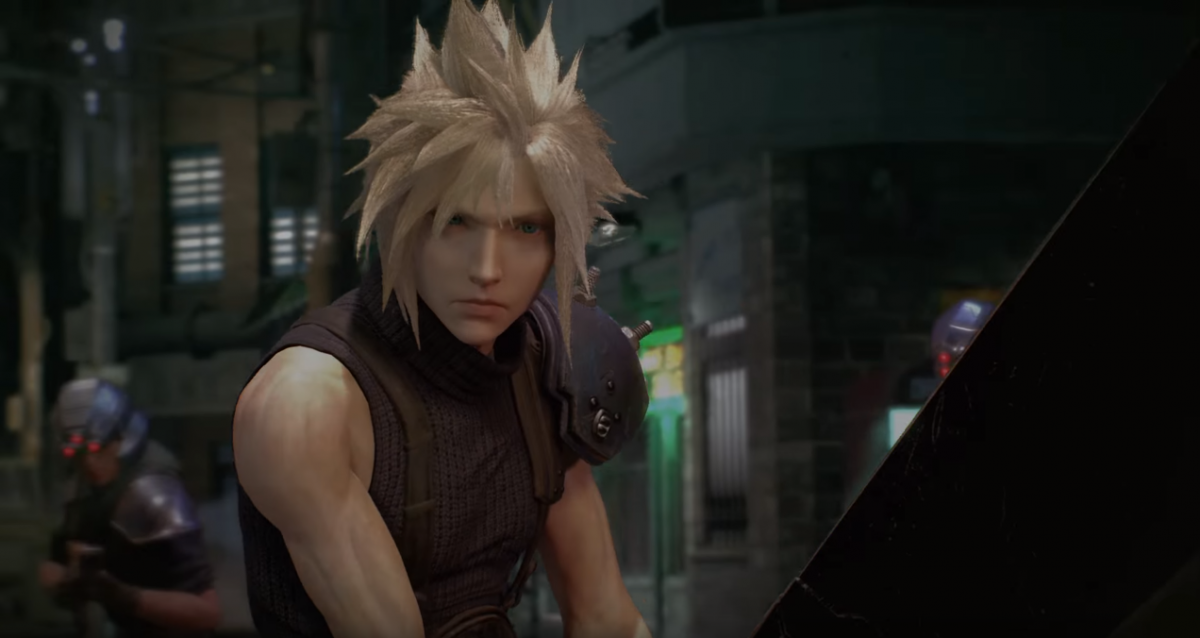

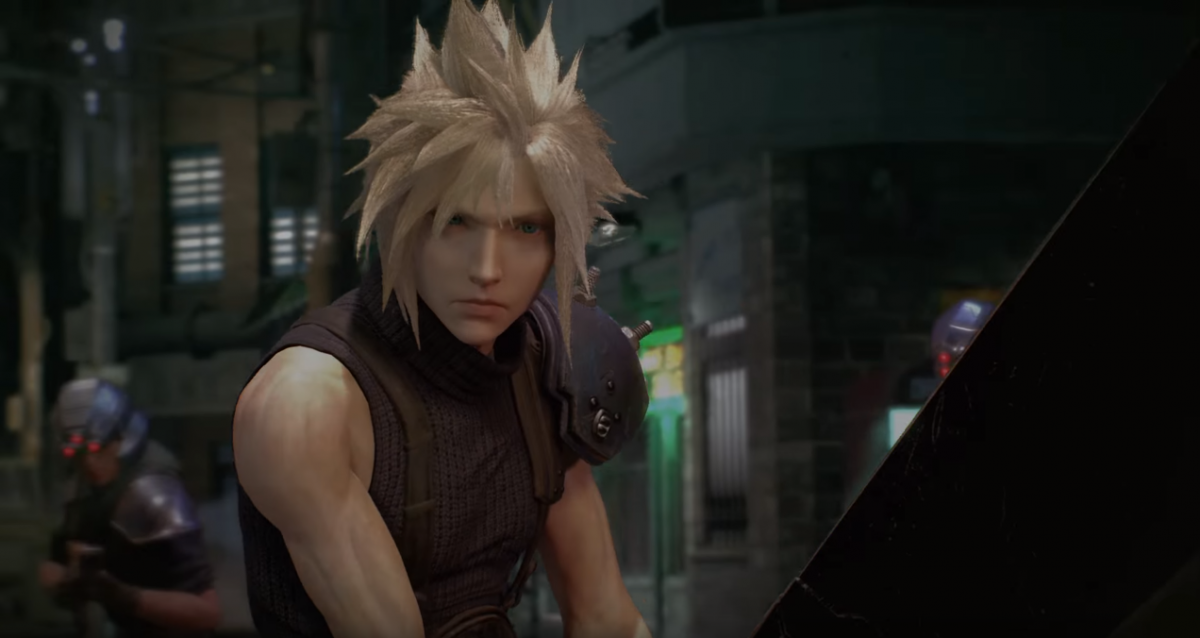

The opening sequences, in Midgar, are fantastic. For perhaps the last time, in its opening few hours FF7 gives us a genuine sense of political and social hierarchy; a group of characters united by a common and easily understood ideal and a familiar-feeling, textured time and place. Midgar is a modern city. We encounter its government, its police force and its everyday citizens, living either in squalor or splendour.

As we gradually navigate from the slums to the top of the highest high rise, we see, in depth, the analogous inner workings and financial echelons of an environment replete with visual and aural wonder. It must be mildly disappointing, for everyone, when they are ejected from Midgar onto the vague and endless world map. What follows almost immediately afterwards, Cloud's extended flashback sequence in Nibelheim, is a telling contrast to those joyous opening hours. Where Midgar encapsulates all that is occasionally great about FF7, Nibelheim illustrates the game's propensity for rambling nonsense.

Nibelheim is where FF7 starts to unravel. Cloud and Tifa's characters become bloated, rather than interesting, and the successive plot twists – first Sephiroth is an alien, then a clone, then the son of Hojo, then Cloud is Zack and Zack is Cloud – are consummate examples of how it can seem as if quantity of writing, rather than quality, is valued in Final Fantasy games.

As a fictional place with recognisable problems, Midgar is carefully and deliberately constructed. The rest of Final Fantasy 7's plot, already hampered by ethereal concepts like the Lifestream, comes too thick and too fast. The death of Aeris endures in people's minds and that's because it's one of few moments actually allowed to sit before another plot twist swallows it up.

It isn't the game's fault per se – trying to compress the requisite amount of audio onto one, or rather three PlayStation discs would have been impossible. But clicking through endless written dialogue, from characters who, thanks to their voicelessness and basic animation, cannot truly emote, turns Final Fantasy 7 into a sluggish, treacly book.

Nevertheless, FF7 still sounds great. The best music belongs, again, to Midgar, but you could hum the tune to Golden Saucer all day, and the Who Are You? track, which plays when you first glimpse the remains of Jenova, is superbly creepy. The final boss fight is fittingly epic – even the most wizened game critic still gets goosebumps seeing Cloud and Sephiroth, face to face, surrounded by endless dark – and the character upgrade system, so often convoluted and obtuse in Final Fantasy games (see 10's Sphere Grid) is perfectly simple. The majority of the game's problems, truly, come down to plot.

Each of Final Fantasy 7's enjoyable individual aspects is swallowed whole by the arbitrary narrative contrivances and seemingly endless written exposition. Perhaps, in its time, these things weren't so egregious; the reason FF7 looks worse, 20 years on, is because so many of its flaws are not only still present in big video games but have become expected, even praised.

Game-makers' predilections for creating lore and building for themselves whole "universes" of books, comics and online TV shows is one of the central reasons writing in games is still difficult to take seriously. Of course, it makes financial sense. If you score a hit like Assassin's Creed, stringing it out across as many media platforms as possible whilst it's popular is prudent. But stories need an ending and characters have to change, or even die, otherwise, as in Final Fantasy 7, the whole narrative starts to feel self-perpetuating, an exercise in seeing how long something can be plausibly dragged on.

FF7 is an occasionally inspiring game, but celebrating it, 20 years on, as a benchmark in video game narrative is to applaud an abundance of sheer content rather than substantive writing. And if Final Fantasy 15 feels empty and strung out, if the plot doesn't really start going anywhere until five, six or seven hours in, it's because it's still aping the mythologised version of FF7.

Like Midgar, which has a concrete sense of place and people, the opening sub-plot of FF15 works terrifically. Accompanied by three pals, Noctis has to take a cross-country road trip to reach his wedding on time, although it's unclear whether he really loves Luna or not. This is an instantly relatable set up. But again, like FF7, which quickly ditches the familiar political environs of Midgar for a gaseous story about Mother Nature, FF15 is eventually a game about old gods, spirit realms and prophecies.

High fantasy and magical realism are not objectionable wholesale. It would mark a sorry state of affairs if, contradictory to its very name, the Final Fantasy series segued into stark social realism. But FF15, like FF7, shoots itself in the foot by starting out with a recognisable, tangible premise and transitioning into something increasingly vague. As stories continue, we should develop, surely, a fuller sense of what is going on and who we are playing; both FF7 and 15 start with, what are for video games, distinct and brave narratives, then devolve into typical fare. And it happens to the latter game only because it is chasing the unmitigated fame and reputation of the former.

In 1997, it was incredible to see a massive, exuberant story brought to such vivid life. 20 years on, there exist dozens of games which are great precisely because they've observed the masses of narrative fat on a game like FF7 and learned to trim it. Rather than turgid explanation, Dark Souls finds its magic in ambiguity and simple, visual flourishes. Mafia 3 is an open-world game, roughly the equivalent length of a Final Fantasy, which finds the beating heart of its story and sticks closely to it. Darkest Dungeon, a turn-based, fantasy game nakedly in the vein of FF, has two familiar, personal experiences understood by anyone who plays it thematic constants: loss and death.

Two decades from now, one would like to think these approaches, not Final Fantasy 7's, will be regarded as "classic".

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.