UK Youth Unemployment: Future Governments Cannot Just Threaten People into Work

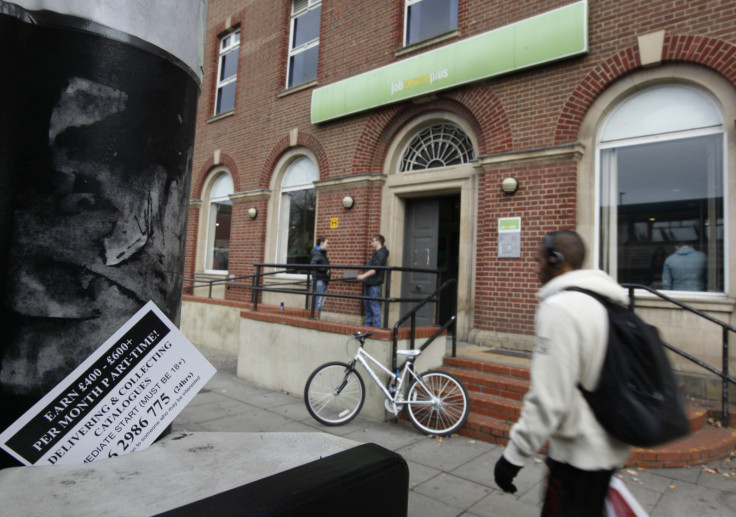

The 'jobs miracle' still hasn't reached the young of the UK. More than 740,000 of them were out of work on the Office for National Statistics' last count – translating into a 16.6% youth unemployment rate.

In comparison, the total jobless rate for the UK is 6.2% – that's a 10.4% gap.

Germany, Europe's largest economy, had a youth unemployment rate of 7.6%. Its total jobless rate was 4.9% – a gap of just 2.7%. Austria had a gap between youth and total unemployment of just 0.6%.

Clearly something is going wrong in the UK. But what? Well, the British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) has identified part of the problem. Firms feel that many young people aren't "adequately prepared" for the workplace after leaving the education system.

The business body, which surveyed around 3,000 companies, found that 76% of respondents reported a lack of work experience as one of the key reasons young people are unprepared for work.

Some 57% of respondents said that young people are lacking basic '"soft' skills", such as communication and team working.

The BCC's solution? It wants, among other things, to introduce universal work experience in all secondary schools.

Universal work experience sounds good. Young people get a placement, skills, and their CV looks a whole lot more attractive to employers. But there could be some serious problems. What if one school had better connections to top businesses than another? We have an inequality of opportunities.

In addition, what do we mean by 'work experience'? Companies, and schools, could have varying views on what they deem to be a 'quality' placement. However, this potential pitfall can be resolved.

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, an HR body, offers some sound advice on this issue. The organisation says, among other things, that a placement should be tailored to a young person's needs and circumstances. That young people should be treated as an active member of staff, and young people should receive open and honest feedback.

It is no good, after all, having universal work experience when some children, who want to be surgeons, are shipped off to the local warehouse, and when others, who want to be tradesmen, are pushed into office work.

But placements are just part of the solution. Careers advice and tracking where alumni get hired is also very important. The BCC recognises this and it's not alone in calling on the government to make sure schools follow their pupils into the workplace.

Sir Michael Wilshaw, Chief Inspector of schools in England and head of watchdog Ofsted, has also backed the idea of "destination data".

The National Careers Council has also warned that a "culture change in careers provision was urgently needed". This is despite the government's introduction of the National Careers Service in 2012. With a "crippling" skills shortage, as the Business Secretary Vince Cable puts it, and high levels youth unemployment, these warnings shouldn't be ignored.

Overriding all of this is investment - investment in young people from employers and the government. The latest skills survey from the Confederation of British Industry and education firm EDI found that only 41% of UK firms planned to increase their investment in training. That research relates to the businesses' total workforce. What hope do 16-to-24-year-olds have you must wonder?

On the government side of the issue, it looks like the UK's two main political parties plan to punish, rather than help, young people.

A Conservative government, David Cameron has told us, would give young people six months to find work or training and they won't be able to claim housing benefit.

A Labour government, Ed Miliband has informed us, would introduce a so called 'Youth Allowance'. The policy isn't all bad – it reintroduces Clement Attlee's contributory principle into the UK's welfare system. But it will mean that 18-21 year olds will only get Jobseeker's Allowance (currently set at £57.35 a week) if they already have the skills to get a job.

Labour have proposed a 'jobs guarantee', though. Under the plan, young people out of work for a year would be offered a taxpayer-funded job for six months. But, if we want to be more like Austria, this isn't good enough.

The country has one of Europe's lowest youth unemployment levels for a reason. In 2012, for example, it spent £273m on young people. In addition, when a young person is out of work for more than three months – not a year – they are offered a job, an apprenticeship or a training opportunity provided by the Austria's job agency.

It seems, therefore, if you want to tackle youth unemployment, you can't just keep hitting people with sticks.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.