Waterloo 200: Three major myths about the historic battle between Wellington and Napoleon

On 18 June 1815, battle broke out near Waterloo in Belgium between the British Duke of Wellington's forces and those of Napoleon Bonaparte, the French emperor. With Wellington's narrow victory came the end of centuries of war between the British (well, mostly the English) and the French. On the 200th anniversary of the battle, we look at three of the biggest myths about it.

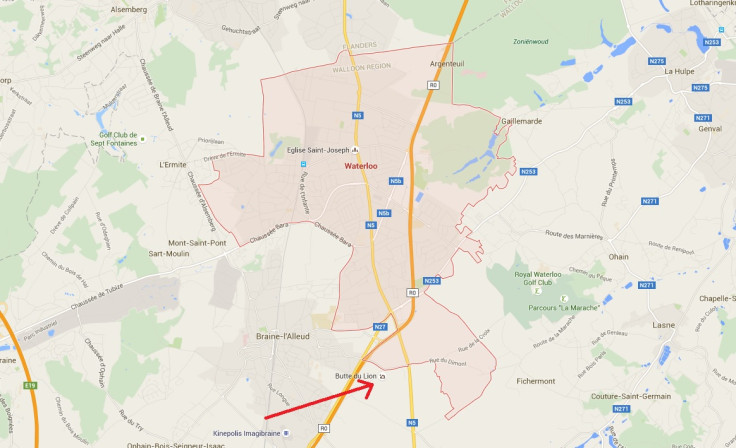

It was fought at Waterloo

It was fought near the Belgian city but just outside of its territory. The battle occurred on land closer to Braine-l'Alleud. Arguably the most famous landmark from it is the farmhouse of Chateau Hougoumont, which held strategic importance and where fierce fighting between Napoleon's and Wellington's forces took place.

Wellington's army was exclusively British

It was not simply a British army but an Allied one. Wilbur Gray writes on HexWar:

In reality Wellington's army of 74,000 plus effectives was only 38% British. A little over 28% were Dutch-Belgians with the rest being a dizzying array of Germans (Hanoverians, Brunswickers and the like).

As the Waterloo Association puts it:

Wellington had around 27,000 British troops. Many of Britain's most experienced troops, veterans of the Peninsular, were in or on their way to America to take part in the war against the new American nation. The 52nd Regiment, which was to play such a crucial role in repulsing the Imperial Guard, was actually in Ireland waiting to sail to America when it was suddenly recalled.

Wellington also had under his command some 40,000 foreign troops, Dutch, Belgian and German, some of who were of unproven loyalty to the Allied cause. Of the 26 allied infantry and 12 cavalry brigades in Wellington's army, only nine and seven were British respectively. Half the 29 artillery batteries were Hanoverian and Dutch.

The Rothschilds received early news of Wellington's victory – before anyone else in England – and made a killing on the markets

"In the summer of 1846, a political pamphlet bearing the ominous signature 'Satan' swept across Europe, telling a story which, though lurid and improbable, left a mark that can be seen to this day," wrote journalist and academic Brian Cathcart in the Independent.

"The pamphlet claimed to recount the history of the richest and most famous banking family of the time – the Rothschilds – and its most enduring passage told how their vast fortune was built upon the bloodshed of the battle of Waterloo, whose bicentenary falls this year."

The trouble is, it was nonsense. Cathcart, author of The News From Waterloo, set about debunking the pamphlet's claims, which he calls The Rothschild Libel.

In quick summary, the story accuses Nathan Rothschild, the founding patriarch of the banking dynasty, of having watched over Wellington's victory before racing back to London. Arriving some 24 hours before news officially reached the city, he exploited this information advantage to make a fortune playing the markets. Which is not true.

While early word of victory did reach London, and was heard by Rothschild (who was in England, not Waterloo), it was brought by an individual Cathcart wrote was "telling his story freely in the City from the morning of Wednesday 21 June – at least 12 hours before the official news arrived. It was published in at least three newspapers that afternoon".

The elaborate myth constructed around Rothschild, who was Jewish, is clearly an anti-Semitic smear – and one that, worryingly, still gets repeated today.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.