China banning foreign media from publishing online is a huge step backwards

One piece of news rippled among China-based foreign journalists last Friday (19 February). According to a document issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, all foreign-invested companies would be banned from publishing online in China, starting 10 March.

"Sino-foreign joint ventures, Sino-foreign cooperative ventures, and foreign business units shall not engage in online publishing services," the document said. Additionally, all online publishers would be required to store their servers, technical equipment and storage devices in China. Except for approved projects, only 100% Chinese companies would be allowed to produce content to be published online, and only after obtaining a license. These companies would be expected to self-censor their materials before publication, according to a series of guidelines.

Although the rules sound wide-ranging, it's unclear how they will be implemented. At this point, we don't know whether the regulations refer only to Chinese content aimed at a Chinese audience; whether foreign media with offices in China are considered "approved projects"; or how non-journalism companies such as Apple and Disney would be affected.

A Hong Kong-based Quartz reporter reached out to a ministry representative but was told that the ministry could only reply to faxed questions from a reporter with a mainland press card.

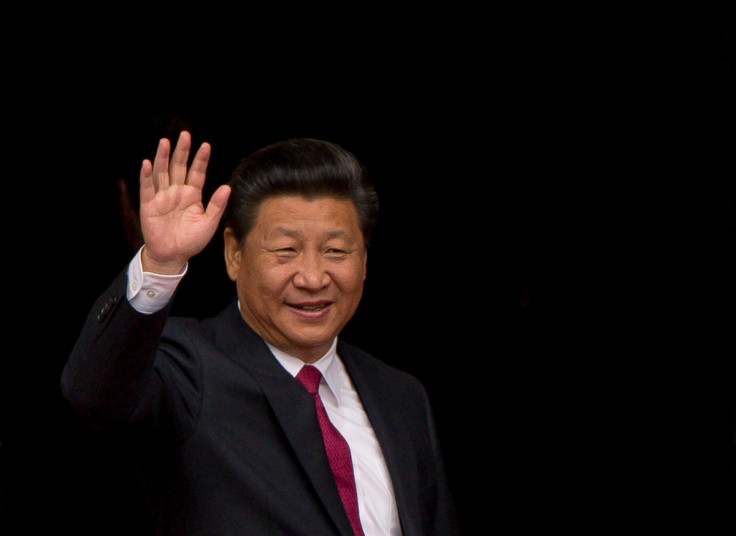

While officials were announcing new regulations on foreign media, President Xi Jinping was busy touring three of the government's mouthpieces: Xinhua News Agency, People's Daily and CCTV. The visits highlighted Xi's desire for the Chinese state media to play a stronger role in shaping the country's image abroad.

"China's Xi underscores CPC's leadership in news reporting," announced a shiny red banner on Xinhua's website following the visit. Although it sounds comical – a country's ruling party wants to take the lead in reporting the news – the headline pretty much sums up the direction Xi wants to set for China's media. Two trends were revealed by events that took place last week and beyond. China appears to want to:

- Minimise foreign and Chinese media's role in portraying China domestically and abroad.

- Groom a select few publications to take on the role of shaping China's image globally. Essentially the CPC wants to direct that coverage itself, based on Xi's vision of "Telling True Stories of China"

Xi has been cracking down on domestic media and dominating the coverage at a level not seen since Mao Zedong, according to some analysts. People's Daily in December featured a front page where 11 out of 12 headlines included Xi's name; page two had nine photos of the president.

Even publications that used to be known for their editorial independence, such as Southern Weekly, are now joining in the trend. Propaganda guidelines are increasingly prohibiting local state-owned media from reporting on events outside their region, and changes in the financing rules for media have made it difficult for independent publications to survive.

Measures to constrict international reporting are raising eyebrows at a time when China's economy is slowing down. Is the government trying to prepare for a rocky period ahead? And how can China assume a more prominent role on the international scene? How can it attract more foreign investment while at the same time requesting that others not peek behind the curtain or say anything negative?

A Beijing-based academic told me recently that China's attempt to limit foreign media was not spurred by the publications' international coverage. Rather the international publications writing in Chinese for a Chinese audience, such as The New York Times, Bloomberg and The Wall Street Journal, are seen as the Western powers' attempt to interfere with China's internal affairs. Western coverage of China is indeed overwhelmingly negative, to a degree we couldn't imagine a foreign correspondent to the US or other countries could attain. But that remains a loaded assumption.

As China is trying to control the perceived damage of unregulated media, it's also working to build a credible alternative voice. A digital-only, state-controlled English-language publication is soon to be launched.

Han Bin, in an editorial for CCTV, put it bluntly:

"China's overall strength has been raised, and criticisms from the West have also been on the rise. Many of the criticisms are regarded by China as purely political or being short of understanding of the country's true situation. The government hopes to change the passive reactive mode and create more effective means of media operation in shaping China's new image globally.

"[President Xi] is not quite satisfied with the current performance of Chinese media. He wants to initiate ground-breaking reforms to boost China's soft power and influence. He hopes the Chinese media can give the country a stronger voice and present a real China to the outside world. "

Han continues: "The media's biggest challenge is to balance the interests of the party, the public, and professionalism."

And this is where Xi's plan risks falling flat on its face. In the rest of the world, journalism is still, thankfully, expected to serve the truth and the public, and no one else besides that. With a different set of assumed loyalties on a global scale, Chinese media won't even be allowed to compete.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.