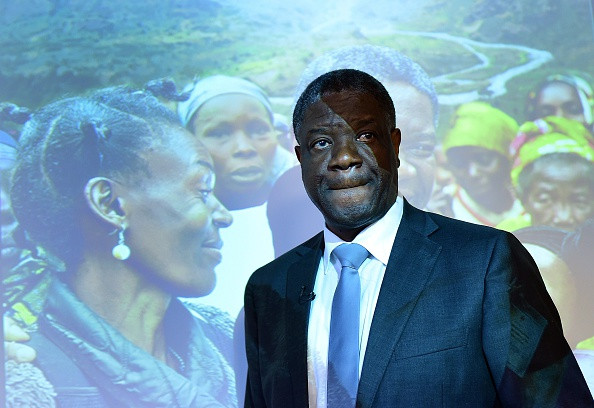

Denis Mukwege: It is time we all acknowledged rape as war weapon destroys humanity

Congolese surgeon Denis Mukwege founded the Panzi Hospital in Bukavu, capital of South Kivu province in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), in 1999 to help pregnant women safely deliver their children and reduce the rate of maternal mortality. As Bukavu, on the border with Rwanda, was and still is marred by widespread violence among various militant groups, the hospital soon became a shelter for thousands of women who were victims of rape and mutilations at the hands of militants and soldiers.

Often labelled as "the rape capital of the world" and "the worst place to be a woman", DRC has one of the highest rates of violence against women and girls in the world.

The Man Who Mends Women

Mukwege, who in 2014 was awarded the Sakharov Prize for his work in protecting women and promoting human rights, founded the Panzi Hospital in Bukavu in 1999.

Mukwege, who has been working in Bukavu for more than 15 years, specialises in repairing the damage caused by gang rapes. It is believed he has assisted some 40,000 women, the majority of whom had been sexually abused.

In 2015, Les Films de la Passerelle produced a documentary – co-financed by Belgium's foreign affairs ministry and the International Organisation of La Francophonie – on Mukwege.

The 113-minute-long documentary, L'Homme Qui Repare Les Femmes, which translates as The Man Who Mends Women, was initially banned in DRC.

Mukwege has operated on at least 40,000 women and girls who were victims of sexual violence and "whose genitals had been destroyed". Known as the "man who mends women", he is today regarded by many as a hero.

However, he believes that every human being is capable of helping others, something he believes becomes a moral duty in time of suffering. The surgeon, who rejected calls to start a political career given his involvement in Congolese society, told IBTimes UK he believes that what is doing is not special. "I am just doing what all humans can do when others are suffering," he explained.

After more than 15 years spent operating on women and girls and helping them cope with traumas related to their experiences, Mukwege believes it is time the Congolese government and international community "took serious steps" to end the use of rape as a weapon of war worldwide.

"People who say that DRC is the rape capital of the world don't understand the problem," he said. "In all conflicts women are victims and we need to agree that the big problem is to understand why this happens. Targeting women and girls in conflict means to use a very cheap weapon, and you can get the same result with rape as if you were using weapons.

"Using rape as war weapon destroys society and it takes a very long time to rebuild it," he continued. "We must fight against this weapon that destroys our humanity".

We must accept rape is happening

Mukwege acknowledged the efforts of the Congolese government and the international community in trying to reduce sexual violence and protect women and girls, but he believes many perpetrators still go unpunished.

I am just doing what all humans can do when other humans are suffering.

"DRC and the international community should get a red line against the use of rape as a weapon of war and I have the impression that no one really wants to make this decision," he said. "We need to push more, we need to raise awareness about what is happening in DRC, but also in Syria, Iraq and other countries where there is war.

"In DRC, many perpetrators are unpunished and they rape again. The big question is: How can these big men who rape women and girls and destroy communities be free even when everyone knows what they did?

"You can't really fight against sexual violence if you do not accept that it is happening," he continued. "Only the government can fight against impunity and it can only start working on solutions if it sees the problem."

Mukwege added that community awareness programs are necessary to help victims of sexual violence be reaccepted by society. "Stigma is a second trauma for them," he said. "We need to help them be reintegrated in communities."

Election

DRC is to hold a presidential election in November 2016 and incumbent President Joseph Kabila is bound by the constitution to step down as he has served two consecutive terms in power. The election could represent the first democratic transition of power after decades of civil war, political instability and deadly coups in DRC.

Kabila's spokesperson has always maintained the president respects the constitution. However, the leader said the election should be postponed, arguing that the country was not ready and more time was needed to revise voter rolls and raise funds.

Earlier in December, the leader called for dialogue with the opposition. However, his proposition was rejected by some opposition groups who argued it was a way for Kabila to cling on to power.

In recent developments, a timetable purportedly prepared by the country's electoral commission (CENI) suggested that presidential election could be delayed by a minimum of 13 months and 10 days. In an exclusive report by IBTimes UK, opposition leader Moise Katumbi rejected the possible election delay while opposition groups are now calling for a day of 'villes-mortes' (dead cities) to ask for the incumbent president to step down.

Mukwege believes that should Kabila cling on to power, DRC will experience more instability and violence against women and girls is likely to worsen.

"The constitution is clear, no one should take more than two mandates and if a leader wants to stay in power for longer, he should say it publicly," he said. "The conflict in Congo is already bad and it will worsen.

"I hope Congo can become a peaceful country where people can ask accountability to leaders. It's my dream to see DRC becoming democratic at the end of this year".

IBTimes UK has contacted the Congolese embassy in London for a statement about sexual violence and Kabila's future political career, but has not received a response at the time of publishing.

Check out our Flipboard magazine - Democratic Republic of Congo by IBTimes UK

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.