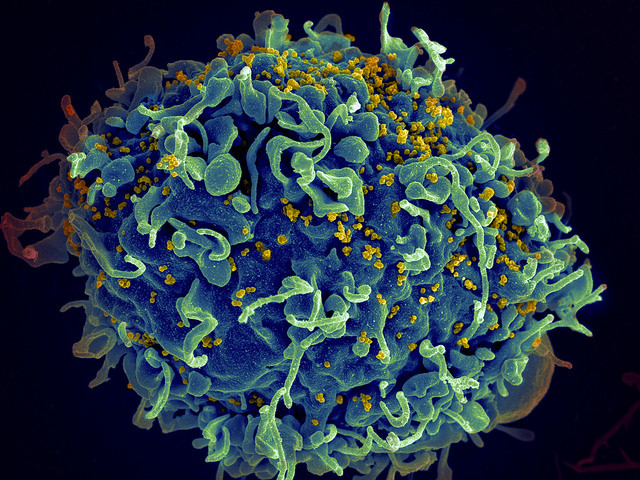

HIV hidden reservoirs detected with new powerful test, bringing scientists closer to a cure

When people stop taking their ART drugs, the virus can re-emerge.

Scientists have developed a test sensitive enough to identify HIV lurking in a dormant state in the body. It appears to be faster and less invasive that the method used currently to track down 'hidden' HIV – and as such represents an important step in the direction of a potential cure.

In recent decades, the life expectancy of HIV-infected patients has greatly improved thanks to antiretroviral therapy (ART), a combination of medicines which slow down the rate at which the virus is multiplying in the body.

Along with robust preventive measures, ART has been instrumental in saving the lives of around 7.8 million people around the world in the last 15 years. ART suppresses the HIV infection to almost undetectable levels.

However, if people stop taking the drugs, the virus can re-emerge. Dormant versions of the virus indeed hide in cellular reservoirs, ready to start replicating as soon as patients discontinue treatment.

This is one of the most important challenges to efficiently treating HIV-infected individuals today to finding a cure.

In a study now published in the journal Nature Medicine, scientists describe a new test which allowed them to identify the virus hiding in the body, and to assess if the detected virus could start replicating again if patients stopped taking their drugs.

Today, clinicians use a test known as "quantitative viral outgrowth assay", or Q-VOA to do this. But they are confronted with a number a problems, in particular the fact that it only provides a minimal estimate of the size of the latent HIV reservoir. In addition, it is not very comfortable for patients as it requires a large volume of blood, and it is labour-intensive, time-consuming and expensive.

The test presented in this latest research is called TZA. It works by detecting a gene that is turned on in patients only when replicating HIV is present. The gene thus acts as a marker for scientists to identify and then quantify the virus.

The test also addresses all previous concerns raised by Q-VOA, as it is much cheaper, requires less blood from patients and can provide results in one week. It could thus represents a very useful tool for clinicians in the near future.

Nevertheless, the researchers believe that using Q-VOA will still could prove useful as the scientific community continues to look for a cure.

"Using this test, we demonstrated that asymptomatic patients on ART carry a much larger HIV reservoir than previous estimates - as much as 70 times what the Q-VOA test was detecting," said senior author Phalguni Gupta, professor and vice chair of Pitt Public Health's department of infectious diseases and microbiology, in a statement.

"Because these tests have different ways to measure HIV that is capable of replicating, it is likely beneficial to have both available as scientists strive toward a cure."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.