How a cow's immune system could hold the secret to a HIV vaccine

Studying cattle could help inform future HIV vaccine development.

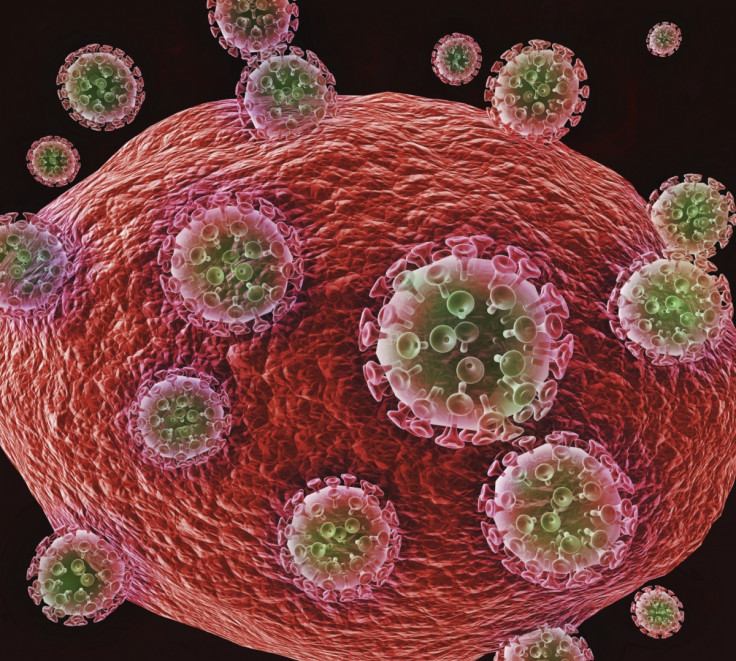

Scientists have made a step forward in the quest to find an HIV vaccine. In a study conducted with calves, they have shown that they could elicit a broadly neutralising antibody response to HIV by immunising the animals with proteins that mimic the HIV envelope.

These findings are promising as they could inform future HIV vaccine design, although it's not yet certain whether they could be replicated in humans.

The human immune system is not able to produce broadly neutralising antibodies against HIV well. Only about 20% of people infected with the virus produce these antibodies, and this usually happens a few years after the infection.

Today, a significant research goal is to produce a vaccine that could generate these broadly neutralising antibodies in every patient, but no initiatives have succeeded to date.

In the study now published in the journal Nature, scientists have worked with cattle, as they hoped that their immune system - which has unique features - would react strongly to HIV immunogens (proteins designed to mimic the surface of the virus).

"For reasons that are complex, humans make broadly neutralising antibodies with great difficulty. But for reasons that are yet unclear, and linked to how the immune system of cows evolved, these animals are able to make numerous powerful broadly neutralising antibodies very quickly when injected with a HIV immunogen," Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which funded the research, told IBTimes UK.

What are broadly neutralising antibodies?

These antibodies are called 'broadly neutralising' because they block and neutralise multiple HIV-1 viral strains.

And indeed, the scientists injected HIV immunogens known as BG505 SOSIP into the flanks of four calves, and showed a quick immune response with a lot of broadly neutralising antibodies created.

All four animals appeared to develop broadly neutralising antibodies quite quickly after immunisation, 35 to 50 days later. In contrast, the length of time required to produce similar antibodies in humans through natural infection is over five years.

The antibodies' long loops

Previous research from people living with HIV for many years have shown that their broadly neutralising antibodies have longer versions of a looped region called HCDR3. These extended loops help to penetrate sugar molecules on the surface of HIV, neutralising the virus more efficiently.

Cattle produce antibodies with long HCDR3 loops at a much higher frequency than humans, which may be part of the reason why they have such a strong immune response to the virus.

Scientists working on HIV vaccine development could use these findings try and promote human immune system's development of long HCDR3 loops. However, it is unclear at the moment how the mechanisms seen in cows could be replicated in humans in practice.

"The study does provide some interesting insight in that a single vaccine protein was able to induce broadly neutralising antibodies. Many have thought this degree of breadth would require a cocktail of proteins. The unresolved challenge is how to make humans respond more like cows," said Robin Shattock, Head of Mucosal Infection and Immunity at Imperial College London, who was not involved with the study.

Another interesting question is whether bovine broadly neutralising antibodies could be used as treatment in humans - although they are not yet suitable for clinical use in their current form.

"Less convincing is the potential use of cow antibodies for treatment - humans would recognise these as foreign and so make a response against the antibody itself. People are working to humanise animal antibodies such that the immune system doesn't recognise them, but this work is in its infancy. It might be possible to use cow antibodies externally - applied to mucosal surfaces - oral, vaginal, rectal to prevent HIV, but there are currently better strategies that are already available - such as pre-exposure prophylaxis," Shattock said.

Exploring how these antibodies are produced so rapidly in cattle is above all important because it might help answer crucial research questions. It may help clear a path for innovative initiatives for HIV vaccine research, which the field so crucially needs.

"It's a novel finding and cows may prove a useful tool in understanding sites of vulnerability against HIV and other pathogens. How easy it will be to turn these insights into approaches that are tractable in humans will be an ongoing story," Shattock concluded.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.