Mosaics in 'Pompeii of the East' reveal moment of destruction that crushed a city 1,200 years ago

The city in northern Jordan was hit by a deadly earthquake in the 8th century.

Mosaics in the city of Jerash lie where they were left more than 1,200 years ago when the settlement was abandoned. A devastating earthquake struck the city in the year 749 CE, after which the surviving inhabitants of the town never returned. Now a house where mosaics were made has been discovered in the city, offering a snapshot in time of an artisan's studio when the disaster struck.

Jerash has been studied and gradually excavated for more than 100 years, but archaeologists are still revealing new aspects of the city at the time of the earthquake. Recent investigation has revealed several mosaics from the Roman, Byzantine and Early Islamic periods.

One building discovered in 2015 stood out as something unusual, described in a study published in the journal Antiquity and found in the north-west quarter of the city.

"This area, covering approximately 3,000 square metres, might almost be termed the 'Pompeii of the East', displaying frozen moments in time," write study authors Achim Lichtenberger of the University of Münster, Germany, and Rubina Raja of Aarhus University, Denmark.

The building was centred around a rectangular room with an arch, opening onto a courtyard. It was well maintained with layers of plaster showing suggesting that it was in the process of renovation when the earthquake hit.

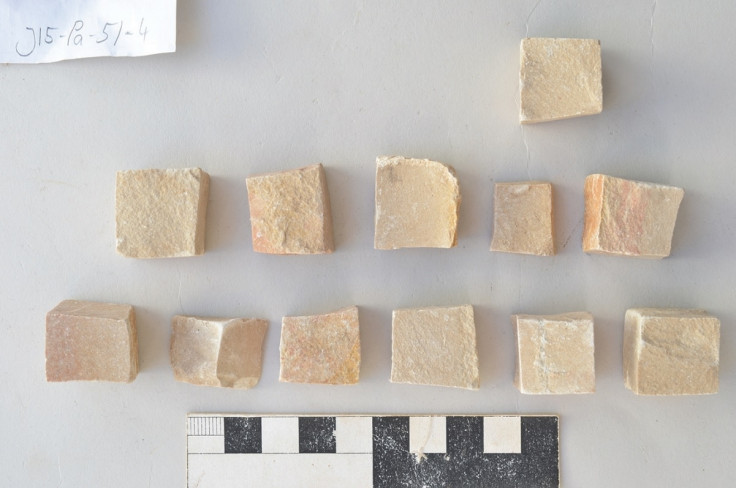

It's thought that the building was a workspace rather than someone's house. A trough full of perfect tesserae – or small cubes of stone for making mosaics – was found at the site.

"The trough served for the storage of tesserae; it was completely filled with thousands of pristine unused white tesserae," the authors write. "No similar installation for tesserae storage had ever been found before. In this case it is clear that the tesserae were unused and therefore part of the preparation for mosaic production."

There has been much debate about how mosaicists worked in this period. Until now there had been relatively little evidence to determine whether they worked in a mobile, travelling fashion or had permanent bases. The discovery of the 'House of the Tesserae' suggests the latter scenario is the more likely.

"The trough in the house at Jerash clearly suggests a kind of storage intended for more than just short-term construction. It could be claimed, therefore, that we do indeed have a studio of a workshop with a tesserae storage facility in the room where craftsmen worked."

But there are still many questions about mosaicists' work left to answer. For example, there were no tools found in the house. It's also unclear where the mosaics were likely to be laid – in a building close by, or somewhere much further away?

"Although many puzzling questions remain concerning the tesserae trough, it constitutes important evidence for the organisation of mosaic production in Early Islamic Jerash and throughout the ancient world in general. It offers a unique glimpse into the moment in time immediately before the earthquake struck," the authors conclude.

"It is hoped that similar structures will be discovered in order to give a better understanding of the practical organisation of Late Antique mosaic workshops in the Levant."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.