Two potent antibodies help monkeys fight HIV - in the long run

The findings highlight the importance of immunotherapy right after an infection to control the virus.

A combination of two potent anti-HIV antibodies has conferred long-lasting immunity to monkeys infected with a simian equivalent of the deadly virus, scientists have announced. They argue that this kind of immunotherapy should be further explored as a way of controlling HIV and facilitating its clearance by the immune system.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a combination of medications that slows down the rate at which HIV multiplies in the body. While it does not "cure" people, it allows them to live a long and healthy life. Along with better prevention, ART is credited to have save 7.8 million lives over the last 15 years.

However, if people stop taking ART, HIV can re-emerge, even if their viral load levels are low. Dormant versions of the virus hide in the body's latent HIV reservoirs, ready to start replicating as soon as patients go off their drugs. This is one of the most important challenges to efficiently treating HIV-infected individuals today.

In the study, now published in the journal Nature, scientists from The Rockefeller University and the National Institutes of Health in the US have hypothesised that antibodies given very soon after an infection could stop viral DNA from integrating into the genome of host cells, and thus prevent the formation of HIV reservoirs.

Such a therapy may induce potent immunity to HIV, allowing the host to control the infection and preventing the return of the virus on the long term.

Macaque monkeys immunity

The team has worked with 13 macaques monkeys which they infected with simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) – a model of HIV infection.

Three days after inoculation – early on in the infection – the monkeys were given three intravenous infusions of two potent broadly neutralising HIV antibodies known as 3BNC117 and 10-1074, over a two-week period.

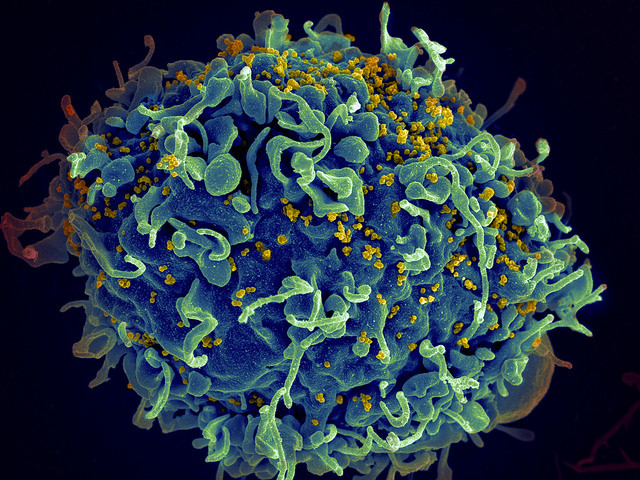

These antibodies were first identified during a previous study looking at elite controllers, a group of rare patients with an immune system capable of fighting the virus. They work by binding to distinct sites on the virus neutralise it and help the immune system clear it from the body.

As expected, the treatment suppressed the virus to low levels with these positive effects lasting up to six months. However, when the antibodies cleared out, the virus re-emerged in all monkeys, except one – in a similar fashion as to what occurs when people interrupt their treatment.

But then, between 5 and 22 months after that, the immune system of six of the monkeys spontaneously regained control of the virus and brought it down to undetectable levels for another 5 to 13 months.

Although they didn't bring it completely under control, four more animals maintained extremely low levels of SHIV in the blood for two to three years after infection.

These findings suggest a beneficial role of the two antibodies on the long-term, even once they are cleared form the body, to control an HIV infection. "Taken together, this indicates that 10 of the 13 bNAb-treated monkeys benefited from early immunotherapy", the scientists write. It is not clear how these findings would be applied to humans but they are hopeful that the impact of the antibodies on SHIV would be similar on HIV.

The researchers thought that immune cells known as CD8+ T cells may be responsible for this long-term immunity.

They tested this hypothesis, providing six of the monkeys with an antibody that targets and depletes these immune cells.

The researchers observed that as the level of CD8+ T decreased, the level of SHIV increased. This suggests that CD8+ T cells indeed play an important role in controlling SHIV replication and that they are crucial to the success of immunotherapy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.