Venezuela's gold rush: Illegal miners face malaria, mercury poisoning and organised crime

Desperate people with dreams of getting rich find they are little more than slaves in a lawless underworld.

With Venezuela's economy in tatters, the country is in the grip of gold fever. Tens of thousands of people from across the nation and from all walks of life are flocking to dangerous illegal mines in the state of Bolivar, as President Nicolas Maduro's socialist government struggles with a three-year recession, spiralling inflation and food shortages.

These unregulated mines are often controlled by organised criminal gangs or armed terrorist organisations. Desperate people with dreams of getting rich often find they are little more than indentured slaves in a lawless underworld plagued by violent crime, hazardous working conditions, mercury poisoning, malaria, human trafficking and forced prostitution.

The head of the Venezuelan Mining Chamber, Luis Rojas, estimates that 90% of the gold produced in the South American nation comes from illegal mines. In a country where the economic crisis has fuelled an epidemic of violent crime, such mines are "primarily in mafia hands", he said.

AFP spoke to a teenaged miner named Ender Moreno. Now 18 years old, he has been working in gold mines for eight years. He labours barefoot and shirtless in a narrow mine shaft filled with deep muddy pools and putrid gases. Handmade wood supports meant to prevent a collapse look precarious at best.

As he climbed through the pitch black, his headlamp lighting the way through the hazardous maze 30 metres (100 feet) underground, Moreno told AFP he wasn't afraid: "I'll probably do this till I die."

The world outside the mine is just as scary. There is a bloody mob war raging for control of the unlicensed, artisanal gold mines. Miners regularly turn up dead, their bodies mutilated or riddled with bullets. Shootouts with assault rifles are common in the region.

Two weeks ago, three young men Ender knew were killed in his neighbourhood of El Callao. Ten months ago, his boss at the mine was killed. The miners say it is because he refused to let mobsters take over the business. Two months before that, 28 workers were massacred at a nearby mine, in what authorities described as a turf war between rival gangs.

At the nearby Nacupay gold mine, workers dig the earth from the bed of a contaminated river as others pour mercury into pans of extracted sediment. The open-pit mine is known as one of the most violent and polluting in the region.

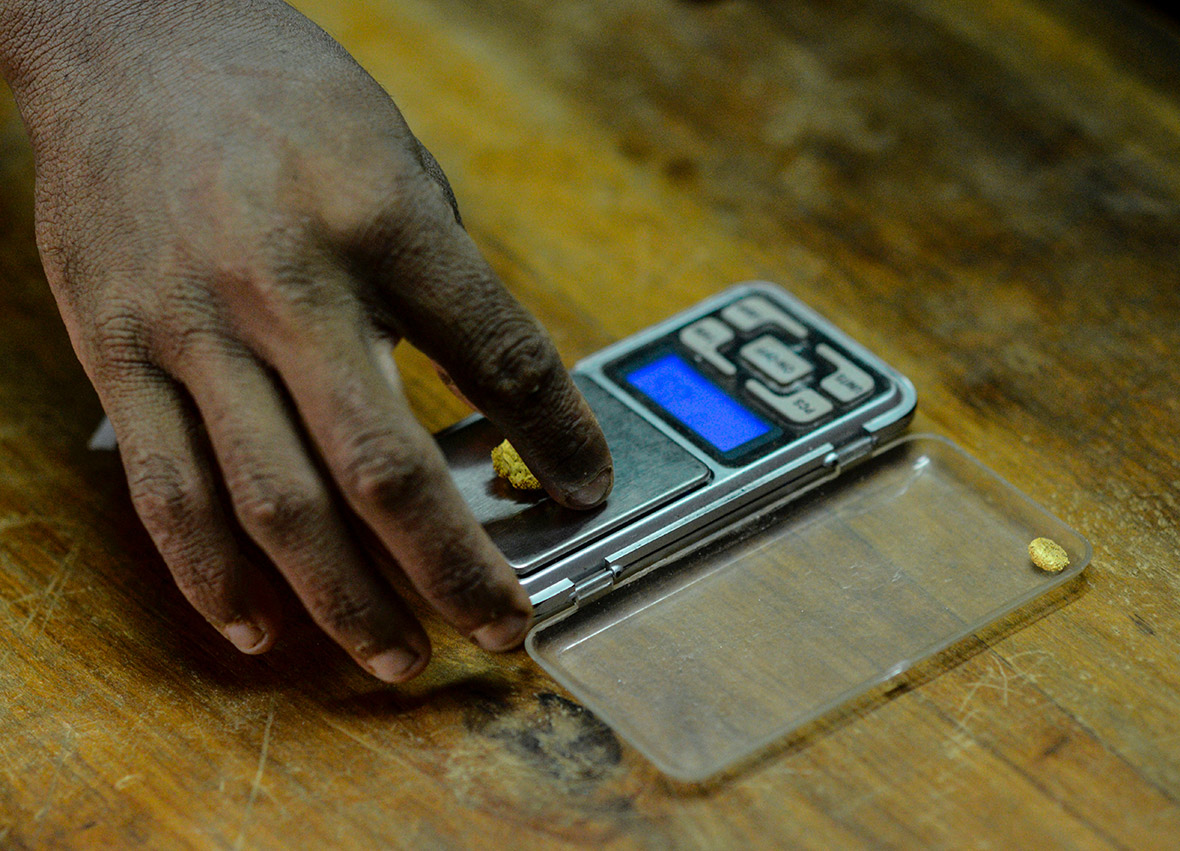

Workers are bused in to the mines every morning, their pickaxes and shovels slung over their shoulders and their pans perched on their heads like hats. Others sleep on-site in malaria-ridden camps built with sheets of black plastic. They make somewhere between 260,000 and one million bolivars a month (£75 to £300 at the black-market exchange rate), they say – far higher than minimum wage.

Mining-related activities are wreaking environmental havoc in the forest, poisoning its wildlife and indigenous people with the unregulated use of toxic chemicals and heavy metals such as mercury. A study published by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation found that 92% of people living in some villages downstream from the mines suffered from mercury poisoning. Slave tattoos with numbers have even been found on indigenous people – many of them children – forced to labour in the mines.

A 2015 research paper by the University of Puerto Rico estimated that between 2001 and 2013, around 168,000 hectares of forest were cleared just for small-scale gold mining, an area about the same size as Greater London.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.