Brexit is a chance to give powers back to Scotland and stop the push for independence

A constitutional convention after Britain leaves the EU could decentralise power across the UK.

British nationhood is, by global standards, solid and venerable. It rests on a common language and culture, shared political institutions, recognised national symbols and a popular patriotism that brought us victorious through three world wars (the Seven Years War of 1756-1763 was surely the true First World War).

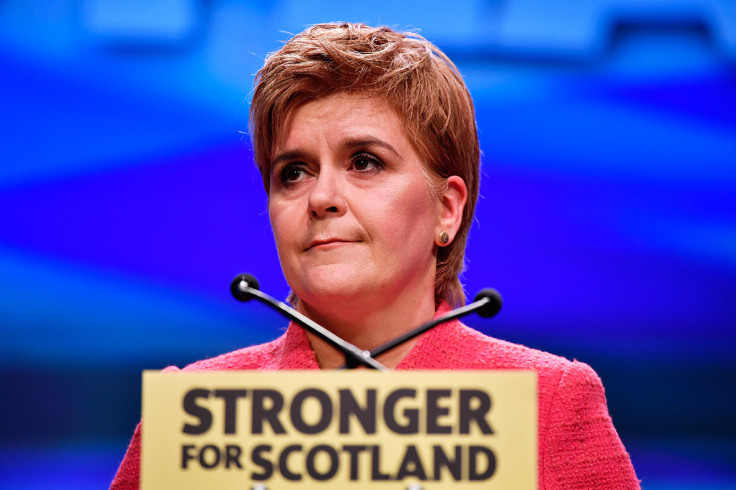

That observation might seem obvious, even trite. But it explains the difference between last year's European referendum and the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, which Nicola Sturgeon now wants to rerun. The European Union (EU) is not a nation, however much its leaders want it to be. It cannot call, as the United Kingdom can, on a common patriotism that rests on centuries of shared identity.

Few British voters feel politically or culturally European. They want a close friendship with Europe, based on a military alliance and trading links; but, with a handful of exceptions, they never wanted a common citizenship.

Some Scots feel the same way toward the rest of the United Kingdom, wanting only an amplified alliance with their neighbours. But others, at least if the 2014 vote is any guide, feel that there is more to it than that. They recognise the symbols of statehood – the Crown, Parliament, the British Army, the pound, the Union flag – as the common property of a nation, not as an imposition by one component part of that nation upon the rest. Those symbols, unlike the EU's common maroon passport or 12-star flag, have genuine emotional resonance for a lot of people.

That's why it is so silly to insist on some sort of automatic analogy between the two separatist movements, or to say "If you favour UK independence from the EU you must logically favour Scottish independence from the UK". It can certainly be argued that, if you wanted a referendum on one, you should want a referendum on the other. But self-determination is not synonymous with secessionism; people can self-determine to remain in a larger unit.

The case for common British nationhood was well put by that Ur-Unionist, James VI & I, in 1604, making his first address (in a heavy Scottish accent) to England's Parliament: "Hath not God first united these Two Kingdoms both in Language, Religion, and Similitude of Manners? Yea, hath he not made us all in One Island, compassed with One Sea?"

No one could say the same of the EU. I write as a convinced Europhile, who speaks French and Spanish and has lived and worked all over the Continent. Europe is an extraordinary place, a cauldron of new ideas and inventions; but it is not a nation.

In Scotland, Unionists were able to make an emotional appeal that EU Remainers never could. Union flags were a major part of the 2014 campaign, whereas we scarcely saw an EU flag in 2016. Nicola Sturgeon knows she cannot appeal ethnic or linguistic distinctiveness, in the way that a Kosovan or South Sudanese or Chechen nationalist could. Throughout the UK, people speak the same language, watch the same TV, follow the same sports, shop at the same chains, sing the same songs.

That said, Scottish identity is plainly not simply a form of regional identity like that of Aberdeenshire or Berkshire. Recognising that identity in a way that stops short of full separation is, if the polls are to be believed, the preferred option of a majority of Scottish voters.

That alone, in my book, is reason enough to deliver it. Gordon Brown has recently called for a form of federalism, in which Scotland could become effectively autonomous in domestic policy, including most forms of taxation. Until now, Labour was the strongest opponent of such an outcome, fearing that it would lose its Westminster majority; but the loss of all but one Scottish Labour constituency seems to have prompted a new attitude.

A federal constitution for the UK would represent the biggest change since the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. It is not something to be done in a rush. All sorts of questions need to be weighed, from what kind of Upper House we should have to the status of the Channel Islands and even the Irish Republic – which, after all, is institutionally closer to the UK than any other state, and might reasonably want a formal say over, for example, how we administer immigration and customs in a border-free area.

Big changes of this kind have tended to happen in Britain for short-term reasons. Our constitution has evolved, as our Union has, organically, haphazardly, in spurts. And none the worse for that: we have an enviable record, compared to most countries, of preserving an open society without either dictators or revolutions.

Let's start the conversation. Let's call a constitutional convention, to conclude after Britain has left the EU. Let's see which Brussels powers can pass directly to Holyrood – or, even better, to Scottish and English local authorities. Let's use Brexit to decentralise, democratise and diffuse power in these islands. And then, when that's done, let's see whether there's still an appetite for separatism.

Daniel Hannan has been Conservative MEP for the South East of England since 1999, and is Secretary-General of the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.