Life after trauma: Giving survivors a new breath of life in Kakuma refugee camp's massage centres

IBTimes UK meets refugee and rape survivor Clarisse, who uses massage therapy to heal herself and others.

Hidden behind a large barrier along a dusty path in Kakuma refugee camp is one Monica's five massage and reflexology centres. There, clients from Somalia, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Burundi come in the hope their physical pains and their troubled souls will be soothed.

Kakuma, Kenya's second-biggest camp located in the country's northeast near the border with South Sudan, is home to 154,947 refugees - the luckiest of whom may receive massages services alongside counselling sessions.

Monica, a South Sudanese refugee and an alternative healing team leader - who currently has 13 masseuses working at this psychosocial project run by the Jesuit Refugee Service - explains the majority of the 1,500 clients need help with emotional problems, stress and muscle tension due to stress.

"It's all about self-worth. To be tended like that shows them they are worth being taken care of," she told IBTimes UK in her office.

But the centre has also become an empowering safe haven for men and women, who receive two-months of training to become masseuses.

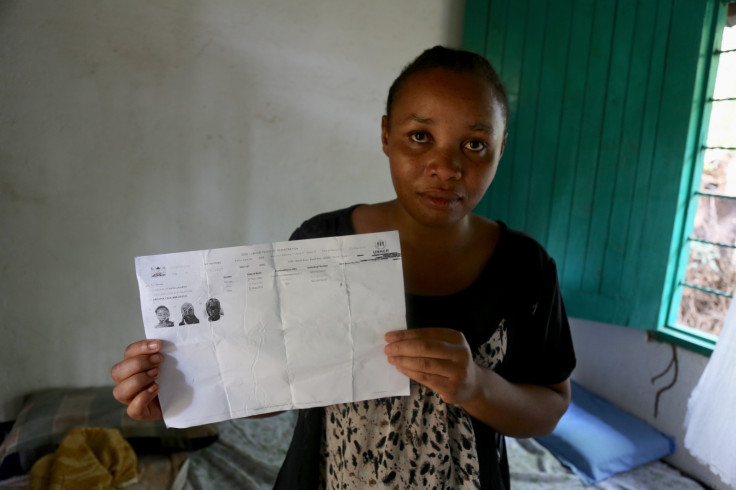

Clarisse, 24, is one of them. The young woman, who speaks almost no English, timidly says she is from Bukavu, the capital of the restive South Kivu province in DRC. After entering the little room where she kneads clients, she stands sheepishly next to one of two wooden beds on which her clients will lay, a tube of shea butter in her hands.

What brought her here? Reverting back to French, the young woman starts explaining she fled in 2013 with her one month old child, Baguma Ciza Abednego, now four.

Her husband, who she married in 2011, was a journalist in Bukavu, she explains. He investigated civilian massacres in Mutarule. He went on the ground to collect information and found out soldiers may have been involved in the killings – or at least knew about it. "People died there, and soldiers didn't intervene during the massacres, they just sat back".

After Clarisse's husband aired the story on radio, he was accused of claiming the soldiers were accomplices in the crimes. His family was threatened. The trio had to flee - immediately.

"We travelled for four days, walking with our bags until a driver of a petrol company found us. When he saw us with our bags and our baby, he took us and transported us," she says, refusing to disclose through which border the driver had taken the family.

"Then we continued our way to Nairobi. We didn't know where we were, or where we were going. A lady, who we spoke to, helped us and put us up in her flat for the night," Clarisse says, her voice picking up in confidence. "Because of the trauma of travelling, tiredness, my child was not feeling well anymore. The lady gave me money and told me where to go and buy milk for him. On my way back, I got lost. It was around 6pm or 7pm, it was getting really dark and I couldn't find my way. I didn't know the area."

At this point in her story, Clarisse does not pause. She just carries on, as if reliving the incident as vividly as the first time.

"I found three men sitting nearby and asked them where I am. They tell me I am in Kangemi, where the lady's house is. But it is dark and all houses look the same, with metal sheets. They tell me they know where the lady is, so I followed them. Then they throw me on the floor, and pull up my blouse. They force my blouse in my mouth and hold it there so I cannot scream. Then they raped me in turn."

Not allowing herself to breathe, Clarisse continues: "I am still on the ground. When they have finished, they flee. No one comes to help me. I pass out."

Clarisse says she has forgotten what happened to her after her ordeal, but knows a passer-by found her lying on the floor and took her to a safer place. "I woke up and it was dark, the person tells me to speak to MSF (NGO Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders) and took me there. I spent the whole of the next day in the hospital, where doctors treated me against HIV. They told me it wasn't my fault," she recalls.

MSF then referred the young Congolese to the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR), and with the help of the community, they helped find Clarisse find her husband and son.

"Then we were taken to the transit place in Nairobi. We spent a month there before we were taken to Kakuma. The UNHCR told us we would find everything in Kakuma – medicine I needed to treat HIV infection, and other infections. I took those for a month." The young woman says she is lucky: after the sexual assault, her husband did not look to isolate or leave her - a fate many women having faced the same traumatic assault have faced in the camp.

Upon arrival at Kakuma's reception centre, the couple were interrogated and given a ration card and a small house in Kakuma 4, the most recent settlement area for new arrivals.

Clarisse now pauses, flattening the bed sheets with her hand. "That's how our miserable life started. We were surviving, we barely eat and my child was suffering – almost malnourished. We were trying to live. We sold our ration[s] because we were hungry. I had stomach problems, menstrual problems – I wondered if that had been caused by the rape," she says, almost matter-of-factly.

Because their asylum process began at the UNHCR offices in Nairobi, Clarisse says the family struggled to applied for resettlement to a third country - a durable solutions for refugees who fled their home country.

"We made official complaints – but were endlessly told our case was still in Nairobi," the young woman, explains, her voice suddenly picks up as if emboldened. "We continued to press them. It took three months. We tried sending emails to the UN in Nairobi. In April (2016), we were called and asked to try and do the eligibility [for the resettlement process]. We are still waiting."

The family settled into life in Kakuma - toddler Baguma started nursery and Clarisse's husband, who by now studied psycho-sociology and counselling, started working for the Refugee Consortium of Kenya.

Two months after starting her training, Clarisse was given a job as a masseuse - a new found role she says has helped reduce her symptoms of post-traumatic stress. This opportunity, she says, empowered her. "Because of my experience I now do counselling for women in my community – women who face marital issues, women whose husband left them and who become single mothers, women whose husbands want to leave them because they suffered rape."

Clarisse, who first appeared as a fragile and frightened young woman just out of her teens, ends the discussion here, as if waiting for the next page of her story - whether in Kakuma, or on a plane bound for one the world's top resettlement countries.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.