After the conviction of a palace aide for corruption - is it time to open up the royal finances?

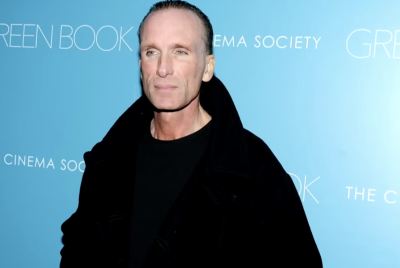

Ronald Harper received £77,000 for helping firms win lucrative contracts at Buckingham Palace

In the secretive realm of the royal finances, it takes a court case to reveal what's really going on behind the palace gates. On September 28, a former deputy property manager within the Royal Household was sentenced to five years in prison for conspiracy to make corrupt payments.

During two trials at Southwark Crown Court it was disclosed that, between 2006 and 2011, Ronald Harper received more than £77,000 ($100,000) in covert payments for helping two firms win contracts worth over £750,000 involving electrical and mechanical work at Buckingham Palace, St James's Palace and Kensington Palace.

The court case raises serious concerns about the robustness of the palace's financial systems, not least how Harper was able to get away for so long with taking what were in effect bribes, and whether it could happen again.

As a deputy manager in the Property Section, he worked with an annual budget of £2.3m and was responsible, according to his job description, "to procure works in the most cost effective manner". His services to the Queen were recognised in 2004 when he was made a Member of the Royal Victorian Order.

Responding to the sentencing, a Buckingham Palace spokesperson said: "We worked closely with Leicestershire Police, providing evidence that helped lead to his conviction. While this was an isolated case, it has reinforced the Royal Household's broader commitment and determination to maintain good governance and prevent corruption."

The procurement process – according to palace sources – has now been revamped so that tendering is overseen by a new central unit, decision-making is monitored through tighter computerised record-keeping and any irregular-looking subcontracting work is scrutinised closely.

It was also noted by the palace that under the new Sovereign Grant funding system – which came into effect after the discovery of corruption - parliament's financial watchdog, the National Audit Office, can now scrutinise all Royal Household expenditure, although it's debatable whether it would have detected what the judge called "the quite brilliantly disguised" scheme of Harper. The court heard evidence of falsified quotes, inflated invoices and disguised payments to third parties.

If it remains surprising that the corrupt practices of a manager in the Royal Household went undetected for five years, it's perhaps less of a shock that the problem arose in the area of property maintenance.

As is clear from the scaffolding currently clinging to Windsor Castle, the Queen's palaces urgently require a facelift and cash has been pumped like liquid concrete into the official residences.

According to the Royal Household's 2016 annual report, £16.3m of its total budget of £40.1m goes on palace maintenance, and that percentage is set to rise. Sir Alan Reid, the Queen's Treasurer and Keeper of the Privy Purse, has predicted that "at least 50% of any increase in the Sovereign Grant will go on palace repairs in future".

With its leaking roof, asbestos-lined basement and falling masonry, Buckingham Palace needs £150m in renovation work to make it, so to speak, refit for purpose. The money will come from the Sovereign Grant, the Civil List's replacement that receives a guaranteed 15% of the Crown Estate income without an annual parliamentary vote. The quid pro quo for this generous supply of public funds was to open up the Royal Household's books to scrutiny from the National Audit Office and its parliamentary adjunct, the Public Accounts Committee.

Prince Charles can designate the majority of his hefty gardening costs as official (i.e. tax deductable) expenditure

A 2014 Committee report on the Sovereign Grant recommended that "there is scope for the Household to generate more income." Buckingham Palace, MPs noted, is open to paying visitors for only a few weeks of the year while the Queen is away in Balmoral, but if admissions were increased, the revenue could be used for palace maintenance. Was this a missed opportunity to maximise a prime asset?

But what was strangely missed by committee members was an attractive Swedish model.

The magnificent 600-room Royal Palace in Stockholm has become one of the capital's most popular and lucrative tourist venues since King Carl XVI Gustaf decided to stop using it as his personal residence, instead allowing it to be open to the public for twelve months of the year. In 2015 it drew 715,200 visitors generating much of the £6.1m total for all palace admissions and helping to make the Swedish royal family one of the most cost-efficient monarchies in Europe.

The king lives in a separate residence not far away at Drottningholm, but when there is a state visit, the official rooms are reopened to allow the foreign dignitaries to overnight there.

Since Buckingham Palace has never been an especially popular home for new monarchs, one wonders why Charles III couldn't follow Carl XVI's example and move out to bring in more cash.

After all, the Prince of Wales makes great play of the fact that he has opened up his current residences to the paying public. Last year 11,000 visitors took the £10 tour of his London home Clarence House, while over 40,000 paid the £25 admission to admire the gardens of his country pile Highgrove House, generating £650,000 for charitable causes.

One of the unintended benefits of turning his herbaceous borders into an attraction for the general public is that Prince Charles can designate the majority of his hefty gardening costs as official (i.e. tax deductable) expenditure. Although the sum is likely to be far in excess of £100,000, it's impossible to work out the exact figure for his garden expenditure from his 2016 annual report as there is no breakdown of the expenses for Highgrove, and the border line between official and private expenditure is often more grey than green.

Confusingly his Gloucestershire house serves both as a private residence where he can unwind with his family and a place of work where he regularly hosts seminars and receptions. To complicate matters further, the house is actually owned by the Duchy of Cornwall. to which the prince pays over £300,000 a year in rent – but since he happens to be the Duke of Cornwall he is just paying himself.

So, if the royals are going to open up their palaces, they could make a start by opening up their finances too.

David McClure is author of Royal Legacy, out with Thistle Books in 2015

*This article was amended on 29 September to correct an editing error.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.