Jeremy Corbyn vs George Osborne: Welcome to the 2020 UK general election

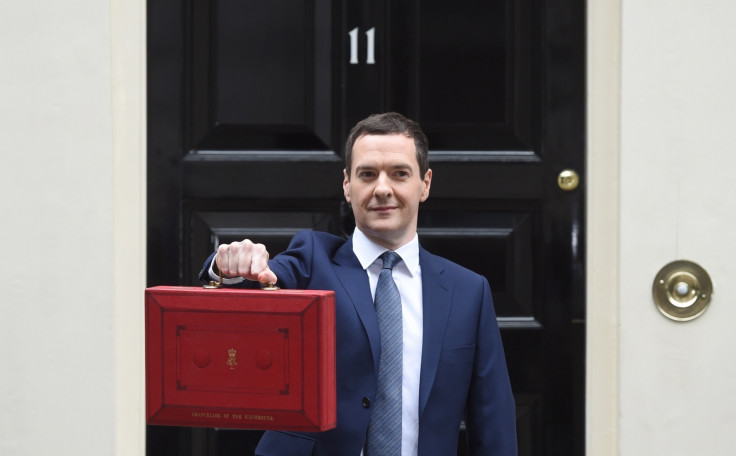

It couldn't have looked much worse for George Osborne in 2012 when, at the nadir of his chancellorship, he was booed by tens of thousands of people at the London Olympics. A double-dip recession. Biting austerity. Falling wages. Rising unemployment. His "omnishambles" budget. The unfortunate default facial expression: an aristocratic sneer. But just look at him now in 2015.

Employment is at a record high. Revised economic data shows the double-dip recession never actually happened. Britain's economy is the fastest growing in the Western world. Austerity continues but Osborne's tough programme was endorsed by an electorate that sent the Conservatives back into office with an unexpected majority.

The chancellor even looks more statesmanlike – he is trimmer, has neater hair, smiles more and has stopped wearing what looks like his dad's suit. He has emerged from the background, willingly, to present himself as the rightful heir to David Cameron's throne in Downing Street.

Osborne and the Conservatives won the debate on the economy and public finances in 2010. Rightly or wrongly, the public generally accepts austerity, that the previous Labour government spent and borrowed too much, and that closing the deficit – so reducing the public debt – is a matter of urgency. Now Osborne and Cameron have done a Blair – taken ownership of the political centre ground. And they've shifted it rightwards.

Nothing shows this better than the first post-election budget, in which Osborne – a one-time free market libertarian who advocated flat taxes – increased the minimum wage to appeal to working people on low-incomes. A massive statist intervention in wages, cheered on by the Conservative backbenches, that snatched the political ground from beneath Labour's feet.

It was a master stroke. It gave him the political space to do something not so centre ground: cut inheritance tax for the wealthy. Osborne knows that if the Conservatives want to hold on to power in 2020, they have to stay as close to the centre as possible, especially when the Labour party is running off to the left with the anticipated anointing of Jeremy Corbyn as leader on 12 September.

"My responsibility as a Conservative is to make sure our reaction to that is to stay where we are, occupying the centre-ground, looking forward, not back, and if they want to go back to the 1980s, let them," Osborne told the New Statesman. "The Conservative Party is not doing that. We're moving forward into the 2020s."

Cameron will not stay as leader of the Conservatives for a third term, ruling himself out of the 2020 general election. That means the battle has already begun to find his successor. His favoured candidate is said to be a close personal friend, someone he has worked closely with over the past decade: one George Osborne. And Osborne's revival from his near death experience in 2012 – there were calls for him to resign, so bad was the state of the economy thought to be –has seen him become favourite with the bookies to be the next Conservative leader.

Osborne's single-mindedness (see his clinging on to the chancellorship when others would have run screaming to the hills); his deadly strategic mind (just look at how he played Labour like a piano over the recent welfare vote); and his determination to occupy the centre-ground from which Westminster elections are won (he managed to get Tories to cheer his wage increase, so his chances of getting them to hold firm look good) mean Osborne is the man to beat in 2020, should he overcome the small hurdle of what will be a bitter leadership battle against the likes of Boris Johnson and Theresa May.

And, of course, he is relying on the ongoing health of the British economy in the face of numerous headwinds, as well as a referendum on the EU that threatens to tear his own party down the middle. One thing he probably doesn't have to worry about, however, is the Labour Party.

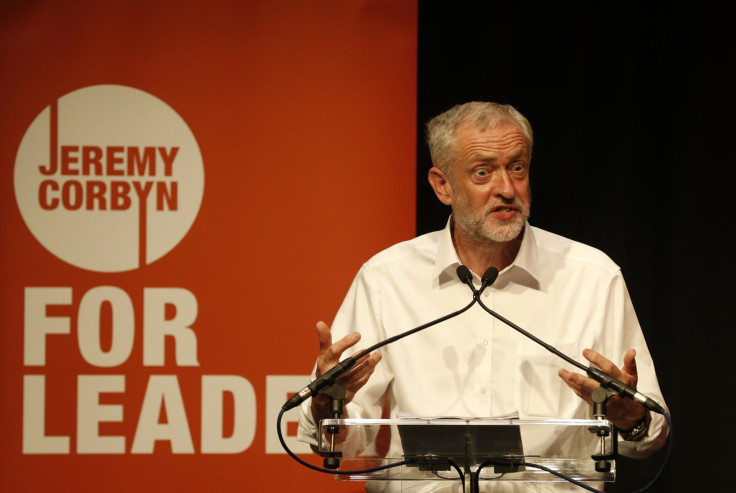

Jeremy Corbyn is storming ahead of his rivals in the race to become the next Labour leader. This is both remarkable and unsurprising. Corbyn says it as he sees it. He is a plain-speaking politician of conviction, a seeming antidote to the professionalisation of politics since 1997 and the managerial style of smoothly delivered soundbites and spin.

He is the antithesis of the Alastair Campbell school of politics. He is anti-austerity, anti-capitalist, anti-Nato, anti-US, anti-Israel, anti-whatever else happens to be faddish in far-left discourse. He is on the hard-left, the sort of gesture candidate who would ordinarily come last in such elections.

But these are not ordinary times. Corbyn's ascendancy is down to the same forces driving the likes of Ukip, Syriza, Front National, Bernie Sanders and the others like them. Anti-establishment, simple-answer, straight-talking politics born out of public frustration at the transactional, compromise, backroom deal making, complex democratic governments we have become accustomed to.

It's the sort of frustration – and some of it is simply ignorance – that leads people to ask simplistic rhetorical questions such as: if we can print money for bailing out the banks, why can't we just print money to spend on welfare? People don't want complexity, they want comfort. And those selling comfort are the simple answer politicians like Jeremy Corbyn and Nigel Farage.

But the trouble for Labour is that it's supposed to be a party of government, meaning it needs to win elections. To do that, Labour has to compromise with the electorate. It has to travel to them, not the other way around. Corbyn is not a man who could win a Westminster general election because he cannot damage the Tories and win back voters from them. He is simply too far to the left for Tory/Labour swing voters. So Corbynites pin their electoral hopes on a series of delusions about Corbyn's attractive powers to three camps: Labour loyalists, defectors and non-voters.

On the first, Corbyn probably can rely on support from party loyalists, mostly because they are what they are: loyal. But some may be tempted to jump ship because Corbyn's ideas are too radical for them, too far from the centre, that they can no longer justify continuing to vote for the party when it advocates the likes of leaving Nato, forcing the Bank of England to print money for public investment, and nationalising entire industries.

On the second, defectors have defected for different reasons. Many left to Ukip and the SNP, some to the Greens. The 'kippers care about immigration because they think there's too much of it, but Corbyn is staunchly pro-immigration. The SNP surge is motivated by nationalism and the desire for a party seen to stick up for Scotland, but Corbyn is anti-Scottish independence and to the left of the SNP, which advocates cutting corporation tax, for example.

And even if Labour had not been all but wiped out of Scotland, it still would not have won the general election. As for the Greens, Corbyn has spoken of reopening coal mines – so good luck winning them over. Besides, winning votes back from the Greens does little if nothing to hurt the Conservatives, which Labour must do for victory.

As a report by the Labour-aligned Fabian Society, The Mountain To Climb: Labour's 2020 Challenge, put it: "Around 4 out of 5 of the extra (net) votes Labour will need to gain in English and Welsh marginals will have to come direct from Conservative voters (in 2015 this figure was around 1 out of 5, because of the Lib Dem meltdown)."

As for evidence of why they are wrong about non-voters, Corbynites need only to look at the unions – most of which, ironically, back their man. In the aftermath of the 2015 general election, the Trade Union Congress (TUC) polled non-voters on their attitudes. Other than "don't know" at 35%, the most popular reason for not voting Labour among non-voters was "they would spend too much and can't be trusted with the economy" at 30%.

Next was "they would make it too easy for people to live on benefits" at 23%. Then "they would raise taxes" at 22%. All of these clash with Corbyn's offering and fatally undermine his supporters' insistence that non-voters will smooth his path to Number 10.

Much of this has been evidenced in polling by Lord Ashcroft of past and present Labour voters, in particular loyalists and post-2010 defectors to other parties. Ukip switchers said Labour no longer stood up for the values it used to have, which will sound like music to a Corbyn supporter's ears –until you discover they all mention immigration as a top concern.

Defectors to the Conservatives said they were uninspired by Ed Miliband's leadership and they didn't think Labour would be competent with the economy. What's more, they thought the Conservative narrative and policy offering – making work pay, the Help to Buy scheme, and so on – was more aspirational and in tune with what they believe than Labour's.

And they are hawkish on welfare, with which Corbyn – who wants to expand the welfare state – is at odds. Corbyn also thinks most Labour voters have moved on from the Blair era and are in fact disgusted by it. But is this true? According to Ashcroft's analysis:

[Much] of the debate within Labour since the election has not been about the party's present or future but, implicitly, about its past. Many within the movement seem to regard the decade from 1997 – in electoral terms, the most successful time in the party's history – as a source of shame rather than pride. Here they are at odds not just with the voters who have since left, but with those that remain. Loyalists, as well as Defectors to other parties (especially the Conservatives) regard Tony Blair as the best Labour leader of the last thirty years. While Loyalists and Defectors overall said John Smith did a better job of standing up for Labour's values, they put Blair ahead on representing the whole country, appealing beyond traditional Labour voters and offering strong, competent leadership; switchers to the Tories gave him a clear lead in all categories. Under Blair, people in our groups recalled, Labour 'were pro-work, but they were fair'; they 'offered the best of public and private'. Moreover, Blair and the voters had a rapport: 'We got him, and he got us.' [...] The party must win over voters who have switched to the Conservatives, the group that differs most in outlook and attitude from those who currently work and vote for Labour. Doing so is not impossible: in my research, very few ruled out voting Labour again even at the next election (though most thought it very unlikely that they would be persuaded in time). But those who have moved away will not return by default.

In essence, there is not a homogenous left-wing block vote of low-to-middle income people on which Corbyn can rely to win a Westminster election. Different potential Labour voters have different priorities, and some of them simply cannot be reconciled. Add to that Corbyn's dubious past, which is currently being raked over, such as referring to the terror groups Hamas and Hezbollah as "friends". Having to bat away revelations and allegations all the time, many of which are perfectly justifiable, is not part of an inspiring alternative narrative.

Welcome to the 2020 general election: Osborne versus Corbyn. On the Conservative side, a man working hard to occupy as much of the centre-ground of British politics as is possible, moving it further right in the process and who has won, against the odds, a general election off the back of a strict austerity programme he has personally enforced.

On the other side, a man desperately trying to escape the centre-ground, alienating the important swing voters there to raise the consciousness of a mythical mass of far-left workers just waiting for their socialist saviour to lead them out of the struggle and towards revolution.

Corbynites must really like living under Conservative rule. Because they're about to select a Labour leader who'll ensure another five years of it after 2020 – and probably an even stronger Tory government.

Whatever you think of Tony Blair, the legacy of his leadership was 13 years of a Labour government which, by compromising with the electorate to secure power, achieved a long list of honourable and laudable things, such as the minimum wage. Corbyn's legacy list of achievements will be much shorter: another Conservative government. Not only a Conservative government, but one led by "Slasher Osborne" at that.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.