Sport's Jimmy Saviles exposed: We can no longer hide from ugly truth

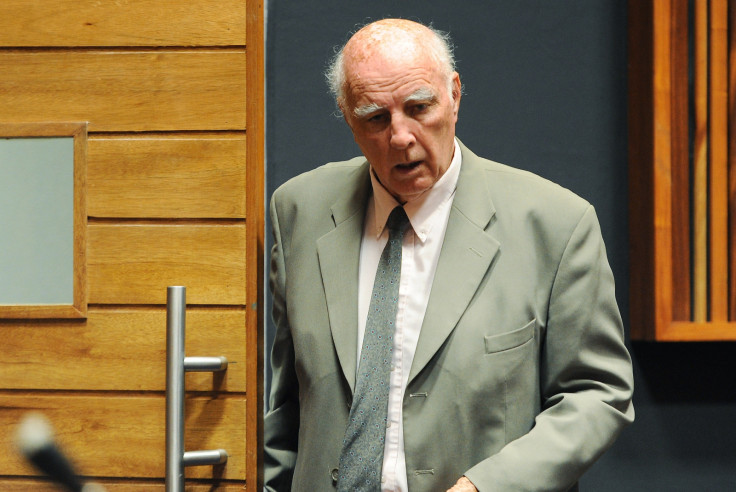

News reports on the trial of tennis legend Bob Hewitt have mostly been cursory. The 75-year-old was convicted on two counts of rape and sexual assault of girls he was coaching in the 1970s. One of his victims was only 12 years old. He was sentenced to six years imprisonment, a lenient sentence on account of his age, and was subsequently bailed, pending appeal.

The former tennis star was subject to a wide-ranging investigative feature by the Boston Globe in 2011 which highlighted a range of other allegations. Perhaps equally distressing, however, were revelations of the extent to which his offences were known about and ignored within the world of elite tennis.

One sports administrator reported his concerns at the time to the president of the South Africa Tennis Union and was told that nothing could be done unless the girls pressed charges. A former Davis Cup team-mate of Hewitt is quoted as saying "We were all praying and hoping he would get his comeuppance, but he never did.''

If all of this sounds eerily familiar, it should. A much admired, important person exploiting his status and position to abuse, rape and molest vulnerable young victims while the institution behind him closes ranks, averts its eyes, avoids any inconvenient scandal.

It is the precise dynamic that operated within the Roman Catholic church, the BBC and elsewhere in the broadcasting and entertainment industries. If there is one surprise in all of this it is that the world of sport has yet to be exposed to the level of scrutiny and revelation that historic events certainly warrant.

There should be no doubt sexual abuse of children was prevalent within sport in the latter half of the 20<sup>th century. Just a week before Hewitt's conviction, a court in Cheshire sentenced professional football coach Barry Bennell to two years' imprisonment for historical child sex abuse offences, his latest in a string of convictions for offences committed both in England and in the US during his career with numerous clubs including Manchester City and Crewe Alexandra.

It was only in 2001 that the Child Protection in Sport Unit was formed in the wake of high profile serious abuse cases, including Bennell's, which had been publicised by a Channel 4 Dispatches programme in 1997. The CPSU oversaw creation of child protection policies and the appointment of safeguarding officers within governing bodies. Criminal Records Bureau checks followed in 2002. Prior to that time, most sports coaching was entirely unregulated.

In a milieu where adults had unsupervised access to children, often in circumstances involving changing and showering facilities or overnight travel and accommodation, it is not difficult to imagine how such a field could become a magnet for child abusers.

Dr Mike Hartill of Edge Hill University is one of the few academics researching in the field of child abuse in sport, and admits that a lack of information about how abusers have operated in the past is a major obstacle to improved protection. He is currently inviting survivors to be interviewed in confidence to help shed light on the problem.

While both boys and girls are at risk from abusive adults, the circumstances and dynamics of abuse can be different. Hartill notes how the macho world of locker-room culture creates conditions that are dangerously conducive to sexual offending. The Penn State scandal in the US is perhaps the best illustration of how a serial abuser such as Jerry Sandusky can exploit team-bonding culture to not only hide his offending, but actively enable it.

Hartill tells me that while policies and procedures have improved vastly over the past couple of decades, there is still much more that could be done. Top of the list is communicating with children and young people themselves. I can vouch for this personally.

When I was between 11 and 13 I attended a junior football club (and simultaneously, a scout troop) that was run by a man who would subsequently be convicted of multiple counts of sexual abuse against my team-mates and friends. We knew something was wrong. We knew it was not normal for a grown man to befriend young boys, invite them to his flat, buy them gifts. We gossiped and swapped rumours, but not one of us really understood the implications, and none knew what to do about it, who or what to tell.

To this day I ask myself what could have been prevented if I, or indeed anyone, had known how to share our concerns with an adult.

Now my own boys are of a similar age, and spending much of their spare time in sports activities of various types. Their mum and I have made damned sure they know what they can and should do if something feels wrong. This, however, has fallen to us. While we have been furnished with pages and pages of child protection documentation, no one at the clubs has taken the children to one side and explained to them what they should do if an adult is behaving inappropriately, that they will not get in trouble if they raise concerns, or anything similar.

Barnardos recently launched an accessible document aimed at teenagers which is a good example of the type of information that needs to be made available to every young person, with facilities such as sports, leisure and youth centres surely a priority. It may well be that our squeamishness about speaking to children about sex, our desire to protect them from the ugliness of the adult world, has actually left them at considerably greater risk.

Organised sports and leisure activities are among the most fulfilling, healthy and essential experiences any child can have, and the overwhelming majority of sports coaches and facilitators are entirely trustworthy, generous with their time and talents and deserving of society's unwavering respect and gratitude.

We owe it to them, as well as to our children, to ensure that the institutions and organisations involved are purged not only of abusive individuals, but also the conditions and culture that allow them to operate with impunity.

Ally Fogg is a freelance writer and journalist based in Manchester, UK, who comments and blogs widely on issues of social justice, politics and male gender issues. He has previously worked in community media as a project manager and as lead author of the Community Radio Toolkit, as an editor and staff writer for the Big Issue in the North, and as an academic researcher in clinical psychology and epidemiology.

He can usually be found arguing with people on his blog at http://freethoughtblogs.com/hetpat/ or on Twitter @AllyFogg.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.