Human Rights Watch: Strong UN police force is only option to stop abuse in Burundi

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has said it is worried the options proposed by the United Nations (UN) Secretary General for a new UN police mission to Burundi may be a "waste of resources and time" as the majority of the proposals would be "ineffective".

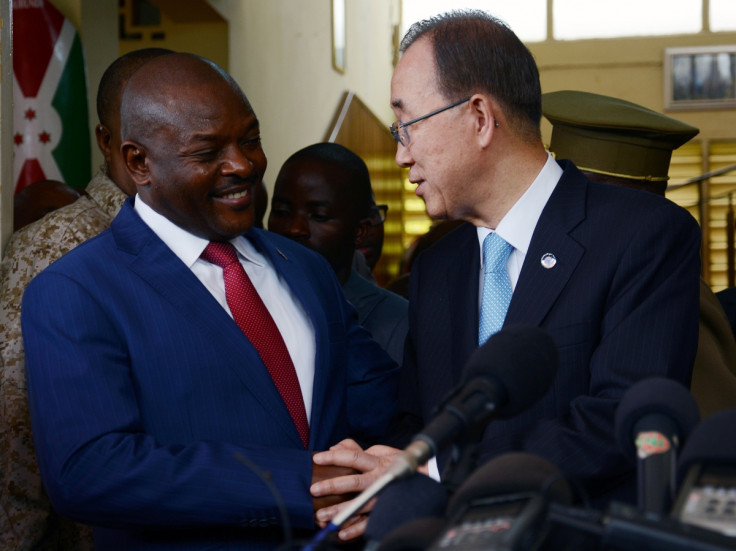

Describing the situation as "alarmingly precarious," Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon on 18 April proposed three options for a new UN police mission to violence-ridden nation (see The UN's three options below) which include dispatching a protection force of 3,000, sending 228 monitoring officers who would not offer protection, with the lighter option being sending between 20 to 50 officers who would assess and advise the Burundian police.

While President Pierre Nkuzunziza quickly said Burundi is only ready to welcome 20 unarmed policemen − rejecting the other options on the spot − Carina Tertsakian, senior researcher in HRW's Africa division, said only the first option would be substantial enough to help stop the abuses and protect civilians.

"We proposed long ago an international police presence, and whilst it's good that the UN is taking this out, we are worried because the only option we believe is worth pursuing is the first one − the protection and monitoring presence. That is a substantial police force, with quite a strong mandate," Tertsakian told IBTimes UK on 21 April.

"The 3,000 figure would probably be acceptable. The two other options, in our view, would be a waste of time and resources. Not only because of the much smaller numbers, but because of the mandates."

Governments 'not trying hard enough'

The Burundian police, as well as the military intelligence and other security forces, are continuing to commit serious abuses on a daily basis − killings, torture, arbitrary arrests − and a tiny police force advising the Burundian police is clearly and utterly ineffective in stopping or even reducing those abuses.

The researcher said the rights organisation was "worried" that a number of foreign governments − which she did not identify − "may not be trying to push hard enough for the first option" and may accept to only send a small police force.

"They (police) would basically be doing nothing, just advising or working alongside the Burundian police. In our opinion that would be ineffective and even worse than that in the sense that it would give the impression that the Burundian government was being cooperative, whereas in reality it's not," Tertsakian said over the telephone.

In recent months, the Burundian opposition, for instance, questioned South Africa's president Jacob Zuma's proposed solution to try to resolve the Burundi crisis, claiming the head of state's alleged "personal interests" had got in the way of pushing for a real resolution.

The rights organisation is calling on the unnamed governments to support the first option "in recognition of the gravity of the situation on the ground".

"The argument is clear. While it is true that the Burundian government said it won't accept a large presence of armed police, we believe that the state members and the UN should at least try to convince the Burundian authorities to accept a presence that stands a chance of at least reducing the level of abuses".

Over the last six years, Valentin Bagorikunda, the prosecutor general, has set up a number of commissions of inquiry into human rights abuses, usually following critical reports by Burundian and international human rights groups, or the United Nations.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.