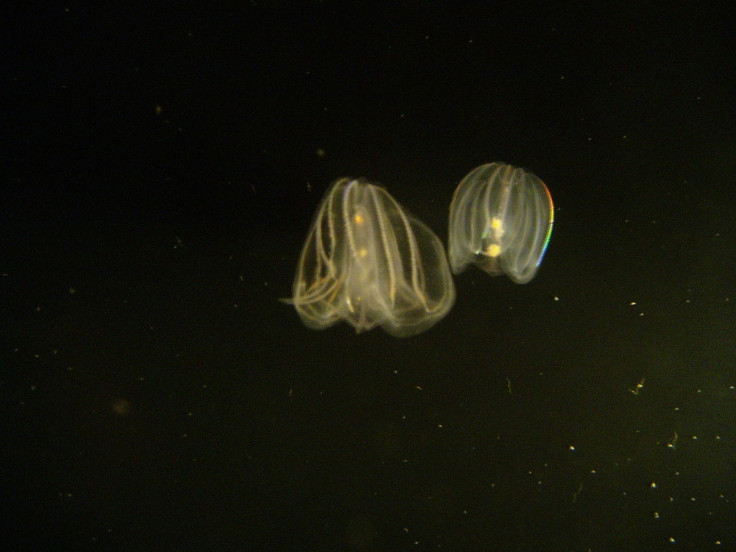

Aliens of the Sea: Comb Jellies Rewrite History to Become 'First Branch of Tree of Life'

A creature that evolved in an entirely different manner to the rest of the animal kingdom has been dubbed "alien of the sea".

Comb jellies took a different path to develop neural complexity and may well be the first branch of the Tree of Life, scientists have said.

Published in the journal Nature, scientists from the University of Florida believe their discovery has implications for synthetic and regenerative medicine.

Researcher Leonid Moroz decoded the genomic blueprints for 10 comb jellies: "By revealing the unique molecular make-up of major features – the development, immune system, nerves and muscles – I can honestly introduce you to the aliens of the sea.

"If you met an alien you would assume it is radically different from us," Moroz said. "There is no need to wait – these aliens are in our backyard."

The comb jellies, also known as ctenophores, independently developed complex organs, neurons, muscles and behaviour far more sophisticated than sponges, which were previously thought to be the earliest lineage.

If confirmed, the findings would rewrite 200 years of zoological assumptions by suggesting there are numerous ways to create an animal.

Authors believe that because the neural development of comb jellies is so different to the rest of the animal kingdom, it could lead to new ways to investigate neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.

"Some ctenophores can regenerate an elementary brain — also known as the aboral organ or gravity sensor — in 3 ½ days," Moroz explained. "In one of my experiments, one lobate ctenophore — Bolinopsis – regenerated its brain four times."

Some of the key differences found in comb jellies include a lack of serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine and most of the other transmitters that control brain activity in other animals.

Rather, they use a mix of peptides and glutamate neural signalling, electrical synapses and genetic editing.

"Our concept of nature was that there was only one way to make a neural system. We oversimplified evolution," Moroz said. "There is more than one way to make a brain, a complex neural circuit and behaviours.

"What if we could not only slow the progression of Parkinson's or memory loss in aging, but reverse it?" Ctenophores show us that there is more than one design for a complex nervous and muscular organisation. Nature is much more innovative than we thought."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.