5 Billion Starfish Dead and Melting: Bizarre Ocean Plague Traced to Killer Vibrio Bacteria

After a decade of gruesome sea star deaths across the Pacific, scientists say a strain of Vibrio bacteria, a relative of the cholera pathogen, is to blame for the largest marine die-off ever recorded.

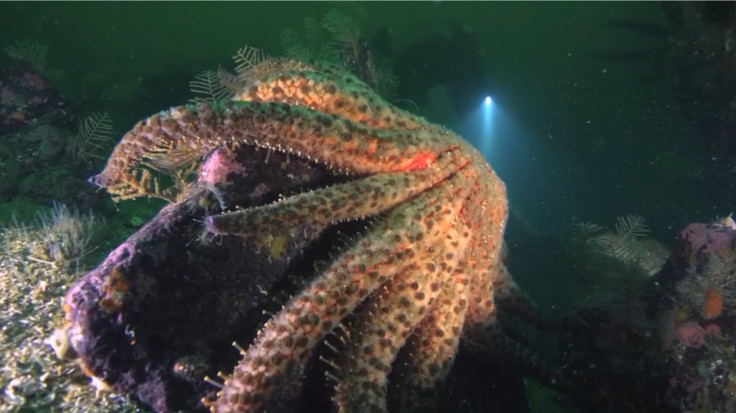

For more than ten years, the Pacific Ocean has played host to a chilling marine mystery. Arms twist violently, limbs tear away and crawl independently, lesions form, and organs spill out. Eventually, the starfish melts into a shapeless puddle.

Now, scientists believe they have finally uncovered the cause behind the death of more than five billion sea stars in what is considered the largest marine epidemic ever observed in the wild.

A new study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, reveals that a bacterial strain known as Vibrio pectenicida is responsible for the outbreak of sea star wasting disease that began in 2013 and continues to impact more than 20 species along the Pacific coast. The bacteria is a close cousin of the microbe that causes cholera and several foodborne illnesses in humans.

The researchers, led by scientists from the Hakai Institute and the University of British Columbia, say the bacteria was found in the internal fluid surrounding sea star organs, a detail overlooked in previous tissue-based studies.

'It's really quite gruesome,' said marine ecologist Dr Alyssa Gehman. 'You see them disintegrating. Their arms fall off and their bodies melt away.'

Twisted arms and mass mortality

The disease has swept from Alaska to Baja California, affecting a wide range of sea star species. The sunflower sea star, a massive predator with up to 24 limbs, has been hit hardest. Since 2013, more than five billion of them have perished.

The situation became so dire that the species was proposed for protection under the US Endangered Species Act in 2023.

'I've felt haunted by the fact that we didn't know what the agent was,' said Dr Drew Harvell, a researcher at Cornell University and the University of Washington. 'This discovery is huge. Without understanding the cause, there was no way to design effective restoration strategies.'

Years of false leads and careful science

Early theories wrongly pointed to a densovirus, but later studies showed the virus existed naturally in healthy sea stars. The new research took a more targeted approach. Scientists studied coelomic fluid from infected animals and discovered the presence of Vibrio pectenicida.

Over four years of experiments, healthy sea stars were exposed to fluids from diseased individuals. Those given untreated fluid developed symptoms and died. Those exposed to heat-treated samples survived, strongly indicating a microbial cause.

Researchers then isolated the Vibrio strain, grew it in the lab, and introduced it to healthy sea stars. Most of the exposed animals dissolved into goo, while unexposed controls remained healthy.

'We ran every experiment multiple times,' said study leader Dr Melanie Prentice. 'Eventually we had to accept that we were right.'

Ecological collapse without predators

The loss of sunflower sea stars has triggered an explosion in sea urchin populations. With no natural predator, urchins have devastated vast stretches of kelp forests, especially in Northern California where researchers estimate 95 percent of kelp coverage has been lost.

Kelp forests are vital marine ecosystems. They serve as nurseries for fish, feeding grounds for otters and seals, and help trap carbon and prevent coastal erosion.

'Sunflower sea stars may look harmless, but they are voracious eaters,' said Dr Gehman. 'Without them, the entire ecosystem begins to fall apart.'

Next steps: breeding immunity and restoring balance

With the cause identified, researchers are now working on breeding disease-resistant sea stars. The long-term goal is to reintroduce healthy populations to the wild, where they can help restore balance to affected ecosystems.

Scientists are also exploring whether warming ocean temperatures contribute to the outbreaks and whether other starfish species are vulnerable to the same pathogen.

'We finally have the opportunity to rebuild what we lost,' said Dr Jason Hodin, a University of Washington biologist who breeds sea stars in captivity. 'But we couldn't do anything until we knew what we were up against.'

Not everyone is convinced the mystery is fully solved. Marine biologist Dr Ian Hewson, who was part of the original densovirus study, warned against assuming a single cause.

'It is critical not to jump the gun,' he told the Washington Post. 'Other species may be affected by different pathogens or environmental stress.'

Even so, scientists involved in the new study say their results offer the clearest path forward in over a decade. For Pacific ecosystems and the species that rely on them, it may finally be a turning point.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.