Astonishing Map Shows Brain on Magic Mushrooms

Psychodelic drugs make unusual, but systematic, connections in users' brains

New ways of mapping brain activity have provided important insights into the way magic mushrooms affect human thought and perception, say scientists.

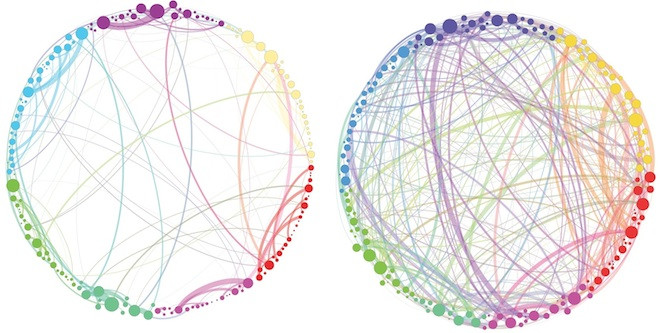

In a recent study focussing on the relationships between neurological centres in the brain, scientists charted the way psilocybin, the psychoactive chemical in magic mushrooms, connects parts of the brain which usually have nothing to do with each other, causing vivid hallucinations, synaesthesia (where different sense react to stimuli, for instance hearing colours) and spritual experiences of connectedness.

The study's co-author Giovanni Petri, a mathematician at Italy's Institute for Scientific Interchange, said that focussing on the brain's activity caused by the drug provided vital clues to how consciousness works.

"In a normal brain, many things are happening. You don't know what is going on, or what is responsible for that," said Petri. "So you try to perturb the state of consciousness a bit, and see what happens."

As part of the study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society Interface, researchers analysed functional MRI (fMRI) brain scans of 15 people who had been given psilocybin, and compared them to the scans of the subjects when given a placebo.

The researchers found that neurological networks in the brain not usually linked became connected in new, but systematic, ways while psilocybin was in effect.

The scientists believe that the connections may give rise to many of the distinctive experiences those who have taken psychedelic drugs report, including synaesthesia, in which one type of experience is perceived in terms of another, for instance colours are heard, or tastes seen.

"[Users] report it as one of the most profound experiences they've had in their lives, even comparing it to the birth of their children," study co-author Paul Expert, a neurobiologist at King's College London, told Live Science.

"We can speculate on the implications of such an organization," wrote Expert in the study. "One possible byproduct of this greater communication across the whole brain is the phenomenon of synaesthesia."

The study is part of a trend in recent years of analyzing the way consciousness works not through focusing on the activity of different parts of the brain, but on the interconnection of neural networks.

Petri said that in future studies the team hoped to focus on how the connections between the networks changed over longer periods of time, and under the influence of different drugs.

He said that the origins of consciousness remained mysterious though.

"The big question in neuroscience is where consciousness comes from," Petri, a mathematician at Italy's Institute for Scientific Interchange, told Wired. "We don't know."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.