Bladderwort: Secrets of carnivorous 'marvel of nature' uncovered by scientists

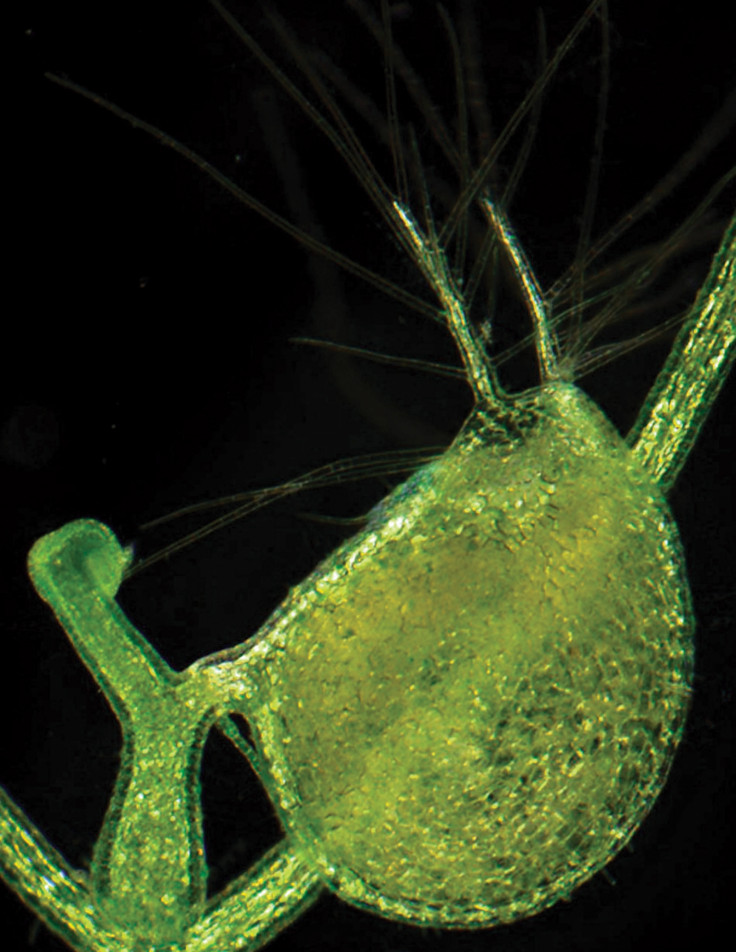

The evolutionary secrets of one of nature's marvels – the carnivorous bladderwort – have been uncovered by scientists. The aquatic plant has no recognisable roots and floats around, catching prey with thread like branches and mini traps that use vacuum pressure.

Now, researchers at the University at Buffalo have broken down the bladderwort's genetic makeup to discover a "jewel box full of evolutionary treasures".

Published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, the authors found the bladderwort has more genes than many other plant species despite having a smaller genome. As a result, the plant has to take part in "rampant" DNA deletion.

Bladderwort (scientific name Utricularia gibba) throughout history has "habitually gained and shed oodles of DNA", lead author Victor Albert said.

"With a shrunken genome, we might expect to see what I would call a minimal DNA complement: a plant that has relatively few genes - only the ones needed to make a simple plant. But that's not what we see."

Instead, the authors find bladderwort has more genes than plants such as grapes. In comparing the two, a bladderwort genome is six times smaller than the grape, yet it has thousands more genes.

In particular, it has a lot of genes relating to its carnivorous diet, allowing it to break down meat fibres. "When you have the kind of rampant DNA deletion that we see in the bladderwort, genes that are less important or redundant are easily lost," Albert said. "The genes that remain - and their functions - are the ones that were able to withstand this deletion pressure, so the selective advantage of having these genes must be pretty high.

"Accordingly, we found a number of genetic enhancements, like the meat-dissolving enzymes, that make Utricularia distinct from other species."

The study showed most of the DNA being deleted is junk. It revealed the bladderwort has undergone three duplication events, where its entire genome was replicated and giving it many redundant copies of every gene.

Albert said: "When you look at the bladderwort's history, it's shedding genes all the time, but it's also gaining them at an appreciable enough rate, permitting it to stay alive and produce appropriate adaptations for its unique environmental niche."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.