From lockdown to strikes: The turbulent life of a Covid-year university student

Covid-generation uni students had their first and second year's disrupted by lockdown rules; now they're set to miss out on more learning due to union strikes.

When you're told about what to expect at university, the description usually involves phrases like "best years of your life", "meeting new people" and "complete freedom". That was certainly what many students had in mind when they submitted their first university applications in college in 2019, before anxiously awaiting the results of their A-Levels.

What they definitely weren't prepared for was three years of Covid lockdowns, online teaching and never-ending strike action. With many Covid-generation university students now in their final year, preparing to graduate, it is no wonder that more than 80,000 are seeking refunds for their costly courses and fees.

Liam Brightley, a third-year student at Nottingham University, is one of them. He describes how a mandatory Covid test and face mask made up the entry requirements just to access his own bedroom - and that would prove to be the tip of the iceberg.

"My "freshers" experience, typically a two-week binge of socialising, partying and making friends, consisted of a few scattered gatherings outside our accommodation block which were quickly dispersed by balaclava-wearing security guards equipped with body-cameras and fining powers," he says.

Clubs, bars and the sports centre were closed, the common room was limited to six, socially-distanced, people at a time and dinner-time rules in the canteen included sitting two metres apart from the nearest person.

"The environment is designed for socialising and interaction, but Covid restrictions meant we were made to feel segregated and alone," adds Brightley.

The effect of Covid didn't just extend to the social experience - lockdown laws and limits on large-group gatherings led to "virtual teaching". It usually involved a lecturer reading their Powerpoint slides through the medium of Zoom or Microsoft Teams - now familiar platforms to most work-from-homers - while up to 100 students sat listening at their desks, or even their beds, as they attempted to take notes. Without real-life interaction, the process was disengaging and unstimulating for both lecturer and student, with most questions posed by lecturers into the virtual abyss greeted by universal silence.

Dean Blackburn, who teaches Political History at Nottingham, says it was "really difficult" for lecturers to adapt. "In two weeks I went from teaching full classrooms to teaching from the corner of a spare bedroom on my laptop.

"Online teaching meant students lost the reward and validation incentive that real-life interaction offers, as well as the collective spirit of classroom learning," he says.

The legacy of this? Blackburn believes the progress of students was hampered, with a clear drop-off in the quality of submitted work. While this temporary arrangement was not the university's fault, many students feel aggrieved that they were being charged over £9,000 in tuition fees to read from slides in their bedrooms. They complained that there was no recognition from academic institutions of the pitfalls of the situation, and certainly, no suggestion of a reduction in costs which many felt was more than justified.

The restricted social and teaching environment was made worse by what some perceived as the militant-like enforcement of isolation and distancing. Universities employed extra security guards to uphold Covid restrictions on campuses and punish those who flouted the rules.

The Telegraph reported that Nottingham Trent University paid £60,000 towards community protection officers supplied by the local council to patrol university accommodation areas. Although most students understood the need for lockdown restrictions at a time when Covid infections were rampant, there was widespread anger at how robustly they were enforced.

At Manchester University, in the middle of the night, fences were put up around the campus to prevent students from going home, while swipe cards that granted entry to non-accommodation blocks were disabled. The next day, thousands of students stormed the campus as part of a wider protest against the way the university had responded to the pandemic, including failing to put in sufficient mental health support. At the end of the rally, students tore down the fences, leading the vice chancellor to apologise for the "concern and distress" they had caused.

On one occasion at Nottingham University, a security officer spotted a potential breach of the six-person rule through the window of a room. He banged on the door and demanded to be let in, before gleefully imposing a fine on those involved. Is it any wonder so many students are reported to have mental health problems? A study of first-year undergraduates at Queen's in Belfast found that around a third had developed moderate to severe anxiety and/or depression.

A year later, lockdown restrictions finally eased, allowing those that suffered a restricted first year to live the "full-uni experience" in their second. For many, however, the damage caused by lockdown laws was already done. They had never met anyone on their course, enrolled in societies or sports teams or broadened friendships beyond those in their immediate vicinity the year before.

Many Covid-year students knew nothing of the place where they lived; travel restrictions had prevented them from exploring their university towns and cities for much of their time there. Normally, the second year at uni builds on the friendships, activities and routines created in the first year. For them, it was like starting from scratch.

For these students, their final year at university may have been the most 'normal', but it has still been affected by external factors. Not a global pandemic this time, but a cost-of-living crisis that has gripped the country, combined with an increase in strike action and boycotts involving teachers and lecturers.

For many students, the maintenance loans offered are not even close to covering the costs associated with university living. The annual increase for maintenance support in the 2022/23 academic year was based on forecast inflation of 2.3%. Inflation, based on the consumer prices index, stood at 11.1% in November 2022. As a result, students are struggling to balance the rising cost of food and bills. One student claims his gas and electricity bill has increased from £56 per month last year to £94.

The impact is that some students have gone without heating or hot water during the winter. A student at Glasgow University says he and his housemates regularly have to generate warmth through electric blankets and portable heaters; ice-cold showers are routine. The mental toll is significant - 90% of students surveyed by the National Union of Students said the rising living costs had led to concerns about being able to eat, feed their family and pay bills and had affected their mental health.

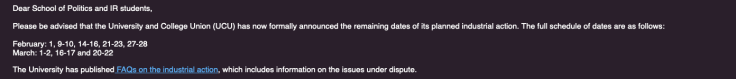

Although lectures and seminars have finally returned to in-person status, last year many courses continued online and they are set to be severely disrupted due to union strikes over the coming weeks and months. This is an email sent to politics students at Nottingham University, outlining the impact of the strikes on their course.

Lecturers are sympathetic about the toll on students but feel they have been left with no choice but to take drastic action.

Dean Blackburn says it's a last resort. "I and many others are giving up our pay during a cost-of-living crisis, and the work I love, as we feel we've been left with no choice."

He cites "temporary and fragile" contracts, a gender pay gap and poor working conditions as the key reasons for the protest. An improved offer to the unions before most of the strikes start on February 13th would be the "ideal scenario", he says, but is not optimistic. The action is likely to go ahead, with several crucial hours of teaching time, as well as pay, lost.

The general consensus among students facing cancelled lectures is that while they understand the reasons behind the strikes, which unions say are a "toxic mix of low pay and excessive workload", they are worried about how the disruption will affect their assignments.

After the cancellations, virtual learning, rules and restrictions of Covid, those dealing with the pressures of dissertations and final year exams now have another unwelcome problem to contend with - incomplete teaching and unavailable tutors.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.