Japan 2011 Tsunami Could Happen Again

Faults in northwest Pacific share same geological features as deadly undersea plates that caused Tohoku devastation

The massive underwater earthquake responsible for the devastating tsunami in Japan in 2012 has the potential to happen again in other parts of the northwest Pacific, scientists have warned.

An international team of geologists has established the cause of the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan's Tohoku region in March 2011 and killed over 15,000 people.

Research papers published in the journal Science show the results from a 50-day drilling expedition at the site of the earthquake.

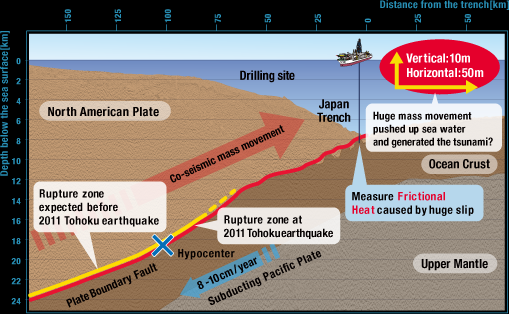

A team of 27 scientists from 10 countries studied the rupture zone by drilling holes in the Japan Trench area - a fault in the ocean floor where two major tectonic plates meet.

Researchers discovered that the tremor was far larger than first assumed.

The joint where the North American and Pacific plates meet form the subduction zone, with the North American plate riding above the edge of the Pacific plate, which bends and plunges deep into the earth.

Until the 2011 quake, the largest displacement of plates recorded on a faultline was in 1960 off the coast of Chile, when a powerful earthquake moved them by 20 metres.

In the Tohoku earthquake, the plates were displaced by an average of 30 to 50 metres and grew bigger as the rupture approached the seafloor. As the plates thrust upwards, the seafloor was ripped apart causing a massive underwater surge which led to the tsumani.

In the case of the Tohoku earthquake, there were two important geological factors that influenced the earthquake and increased its power.

Researchers found that the fault was very thin at less than five metres thick. By comparison, the San Andreas fault in California is several kilometres thick.

Christine Rowe, of the McGill University in Quebec and part of the team involved in the expedition, said: "To our knowledge, it's the thinnest plate boundary on Earth."

Another contributing factor was that the clay deposits filling the narrow fault were made of extremely fine sediment: "It's the slipperiest clay you can imagine," she said. "If you rub it between your fingers, it feels like a lubricant." The fine clay allowed the rock to slip very easily.

Researchers were concerned by the discovery of the fine clay because it had also been found in a number of other subduction zones in the northwest Pacific, including alongside Russia's Kamchatka peninsula to the Aleutian Islands.

The clay in these zones could be capable of generating similarly huge earthquakes, Rowe warned.

J Casey Moore, a research professor of Earth sciences at UCSC and co-author of one of the studies, added: "Looking for something like that clay may give us a tool to understand the locations of earthquakes that cause tsunamis. It's potentially a predictive tool."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.