AI Giants Sued: xAi, Meta, Google And OpenAI Under Legal Fire by Just One Man

Copyright Clash: How AI training practices put OpenAI, Meta, Google and xAI in legal trouble

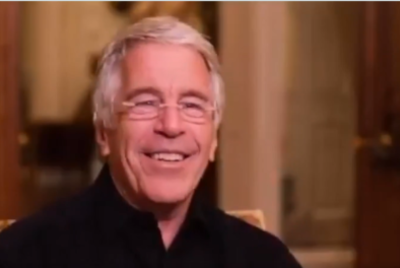

Have you ever questioned how ChatGPT or any other AI you use to ask questions or do research gets all its information? Well, that very method, so to speak, of how AI gets its information is now seeing a big legal fight. One man, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, has taken on some of the most powerful technology companies on the planet.

That man is John Carreyrou, an investigative reporter, who filed a lawsuit in a federal court in California against a number of major AI developers including Elon Musk's xAI, Google, OpenAI (who is the maker of ChatGPT), Meta Platforms, and Anthropic and Perplexity, for allegedly using copyrighted books without permission to train their advanced chatbots.

Big Tech AI Giants Sued

The main part of this lawsuit is the allegation that tech giants have been feeding their large language models with alleged pirated copies of copyrighted books, all without securing licenses or paying authors for their work fully. Carreyrou, alongside five other authors, reportedly claim that these companies exploited their books to train generative AI systems that power chatbots, helping these models to produce a big range of human like text.

This contentious case was filed on 22 December 2025 in the US District Court for the Northern District of California, and the complaint says that the defendants engaged in what the plaintiffs reportedly describe as 'a deliberate act of theft' by using protected literary works in the training datasets of their AI models. This tactic, they allege, ended up in the creation of tools that now compete in the marketplace without proper compensation to the original creators, it seems.

However, unlike many copyright cases involving AI, the plaintiffs in this lawsuit chose not to pursue a class action. This is because they reportedly think that combining their problems into a single collective case would weaken individual claims and help the powerful corporations to settle on terms that might only offer nominal compensation.

This might be a smart move because something like that has happened before, for example as per reports, an earlier class action settlement between Anthropic and authors resulted in a payout of 1.5 billion US dollars ( £1.2 billion approx), but some within the current action said that this would amount to only around 2% of the maximum statutory damages per infringed work, a fraction many considered inadequate. So, by acting independently, Carreyrou and his fellow authors hope to get what they possibly view as fairer outcomes that show the true value of their intellectual property.

Furthermore, the defendants, on the other hand, have yet to publicly offer detailed statements on this specific complaint as of this writing. In similar legal battles before this, AI developers have many times maintained that their training practices fall under doctrines such as fair use, which in US law permits some unlicensed reuse of copyrighted material for research or transformative purposes. However, copyright holders have again and again challenged these claims in court, saying that the scale of data usage in training AI models is much more than the scope of what fair use was intended to cover.

Read More: Did AI Take Over 50000 Jobs in 2025? Who Should Watch Out in 2026

Read More: Google's Biggest Weakness Exposed by ChatGPT Maker Sam Altman

How AI Systems Use Information for Data Training

Now, to understand why this lawsuit has gotten so much attention, it is helpful to know how AI models are trained and why the source of training data matters so much. Large language models, like those developed by OpenAI, Google and others, learn to generate coherent and contextually appropriate text by analysing massive datasets comprising text from books, articles, websites and other sources. Moreover, during training, the model processes this data to detect patterns in language use, grammar, semantics and context.

Then, over time, these systems gather up statistical knowledge about how words and phrases relate to one another, helping them to generate new text that can mimic human writing with great fluency.

However, the way in which training data is gathered is what is super contentious. Many AI developers say that they use publicly available information and that the training process transforms raw data into generalised statistical models rather than storing or reproducing specific content. Critics, however, including some authors and news organisations, argue that models sometimes produce outputs that are too close to the original text, saying that the material was effectively memorised and reused without authorisation.

This then leads to complicated questions about intellectual property rights, memorisation, and whether current legal rules are good enough to handle the realities of modern AI training practises. These technical nuances are now being looked at in courtrooms as plaintiffs seek to show that their work was not just used as general inspiration but was an important part of the AI training process.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.