Earth's Oceans May Have Formed From Crashing Comets

Scientists have discovered for the first time found water on a comet like that on Earth, supporting the argument that oceans were formed by crashing comets.

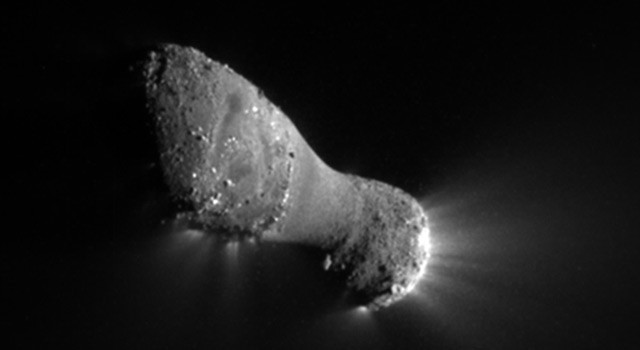

The discovery, which was found on Comet Hartley 2, strongly suggests that the Earth's seawater arrived as a result of collisions with ice-packed comets billions of years ago.

Using the Herschel space telescope, astronomers at the University of Michigan found the comet carries ice with the same composition as our oceans.

"We were all surprised," said Professor Ted Bergin.

"Life would not exist on Earth without liquid water, so the questions of how and when the oceans got here is a fundamental one (sic)," he said.

"It's a big puzzle and these new findings are an important piece."

Just a few million years after its formation, the Earth was a dry and rocky place, with a heat so intense any water would have quickly evaporated. This has led scientists to believe that the oceans emerged around 8 million years afterwards.

Previous models of early Earth implied that most water came from asteroids.

In the case of Hartley 2, researchers found that ice on the comet has a near identical "D/H" ratio to seawater. D/H measures the proportion of deuterium - or heavy hydrogen, which has an extra neutron - compared to ordinary hydrogen in water.

Six other comets have been studied by the Hershel Space Observatory in recent years but all carried ice with different chemical compounds. This led scientists to conclude that comets could not have contributed more than 10% of the world's water.

But Hartley 2 was born in a different part of the solar system to the other six comets that were tested.

"The results show that the amount of material out there that could have contributed to Earth's oceans is perhaps larger than we thought," said Professor Bergin.

The research is published in the science journal Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.